Lego Fascists’ (that’s us) vs. Fox News

What’s so wrong about questioning modern American values such as consumerism and militarism?

What’s so wrong about questioning modern American values such as consumerism and militarism?

Supreme Court rulings affecting Louisville and Seattle could wipe out the last vestiges of the 1954 Brown decision.

It wasn’t just the hurricane that devastated the Gulf; it was also a slower, more preventable surge of racism and poverty.

At a recent conference in the north of England some two or three hundred local politicians, directors of education, and a smattering of trade unionists and teachers attended a conference […]

If we ignore race and money inequities, small school reform won’t help anything meaningful take root.

The Dec. 26 tsunami swept away the lives of more than 200,000 people and ravaged the livelihoods of millions more. Throughout the world teachers and students discussed the tsunami and […]

The ideas presented in this article are discussed at greater length in Dr. Olfman’s upcoming book Childhood Lost: How American Culture Is Failing Our Kids (Praeger Press) in which some […]

Encourage movements for social justice at the national level.

So often, the climate crisis is presented in frightening, threatening terms: rising seas, superstorms, raging wildfires, unlivable temperatures, species extinction, disappearing glaciers, dying coral, climate refugees. These are real. But the paradox is that this dystopian possibility is forcing us to imagine an entirely different kind of society. Schools have a central role to play in devising new alternatives and equipping young people to bring those alternatives to life. This is the work we’ve been assigned.

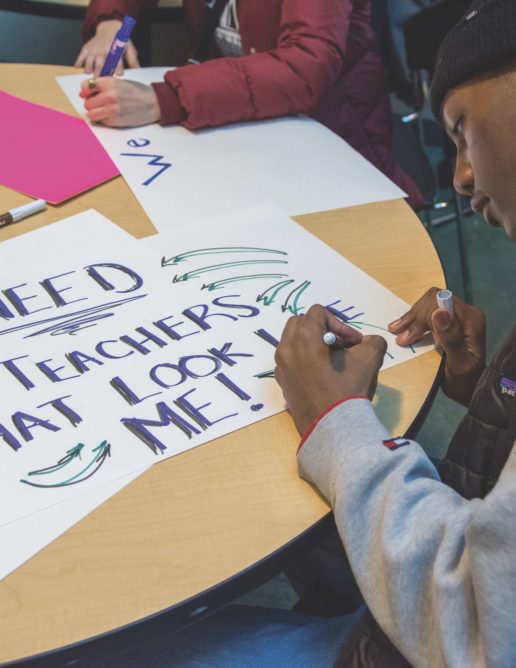

Every social justice educator should make building the BLM at School Week of Action during the first week of February a top priority.

If there was ever any doubt, now there is only certainty, as educators we’re on the front lines of this fight. And when students like Kina ask us if we can keep them safe, our actions must be our answer. If we refuse to talk about these issues — because they are too painful, too complicated, too sensitive, or too politically fraught — that sends a clear message that we have relinquished our responsibilities, as adults, to try to keep them safe. Our silence is complicity. Now is the time for action and solidarity.

How we seed and support student activism will vary from community to community, school to school, and grade level to grade level. But this is a crucial moment in history, and what we do as educators matters. When we help students explore and analyze exploitation, injustice, and danger in the world, we can also help them develop the knowledge and skills to change it.

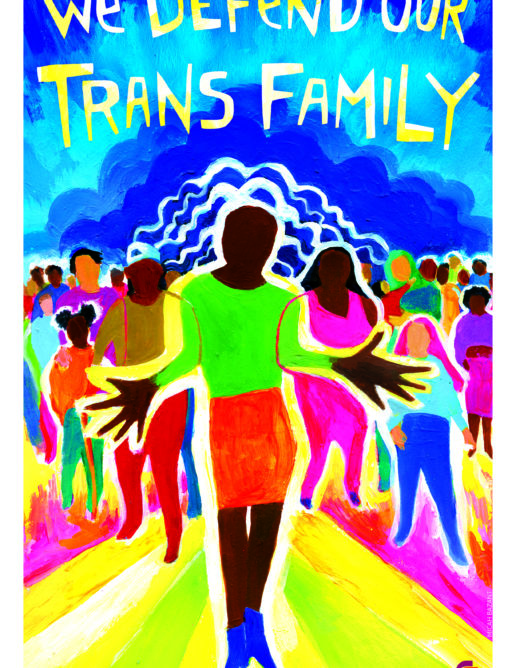

What can teachers, schools, and districts do to meet the needs of trans students? To make them visible? To keep them alive? To celebrate them?

The second installment of our new environmental justice column focuses on one part of a resolution passed by the Portland, Oregon, school board that mandates the school district not use text material that doubts “the severity of the climate crisis or its root in human activities.”

There’s much that we as educators can do to combat gun violence and get guns out of our schools. One of our roles as teachers is to guide students to examine the roots of an issue.

They’re calling it the “Education Spring,” and what started in a rural county in southwest West Virginia has spread like wildfire and inspired teachers and other public sector workers across […]

In May 2016, while I was carrying out ethnographic research in the Kakuma Refugee Camp in Kenya, a Form 4 (12th grade) history teacher asked me if I would teach his students about U.S. democracy. We flipped through the history and government textbook to one of the last chapters where the national curriculum outlined political systems in Kenya, England, India, and the United States. It was a peculiar moment to put the U.S. democratic system on display.

The ongoing, persistent verbal and physical violence against women, youth, and LGBTQ communities has not been adequately addressed in most schools. Instead of educating children and youth about gender equity and sexual harassment, schools often create a culture that perpetuates stigma, shame, and silence. Student-on-student sexual assault and harassment occurs on playgrounds, in bathrooms and locker rooms, on buses, and down isolated school hallways. Students experience sexualized language and inappropriate touching, as well as forced sexual acts. And they encounter these at formative stages of their lives that leave scars and shape expectations for a lifetime. What isn’t addressed critically in schools becomes normalized and taken for granted.

During a recent conversation, a former high school classmate said, “I always wondered why you left Eureka. I heard that something shameful happened, but I never knew what it was.”

Yes, something shameful happened. My former husband beat me in front of the Catholic Church in downtown Eureka. He tore hunks of hair from my scalp, broke my nose, and battered my body. It wasn’t the first time during the nine months of our marriage. When he fell into a drunken sleep, I found the keys he used to keep me locked inside and I fled, wearing a bikini and a bloodied white fisherman’s sweater. For those nine months I had lived in fear of his hands, of drives into the country where he might kill me and bury my body. I lived in fear that if I fled, he might harm my mother or my sister.

I carried that fear and shame around for years. Because even though I left the marriage and the abuse, people said things like “I’d never let some man beat me.” There was no way to tell them the whole story: How growing up and “getting a man” was the goal, how making a marriage work was my responsibility, how failure was a stigma I couldn’t bear.

As we return to our schools this fall, we need to rededicate ourselves to building an education system and a society that values Black lives.

Rethinking Schools was born in the time of Reagan. We celebrate our 30th anniversary in the time of Trump. We know something about holding on to hope during hard times. […]

Recently, a Rethinking Schools editor was a chaperone on a field trip when he overheard a 2nd-grade student talking about how he wanted to “nuke the world.” Taken aback, he […]

This is the first issue of Rethinking Schools magazine in eight years for which Jody Sokolower was not the managing editor. Jody stepped down in April to focus on local […]

Repensando las escuelas nació en la era de Reagan. Celebramos nuestro décimo tercer aniversario en la era de Trump. Sabemos algo acerca de mantenernos esperanzados durante los tiempos difíciles. Hace […]

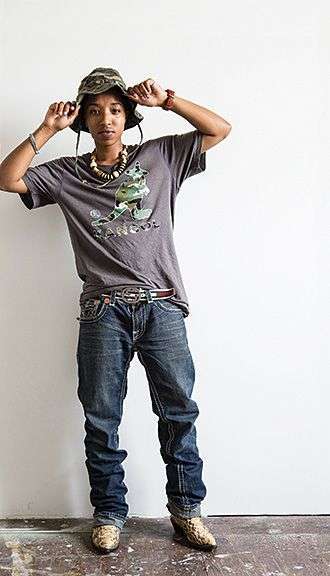

The youth on our cover is Lana “kQween” Grant. She was photographed by Lois Bielefeld as part of her Androgeny series. kQween’s pride—and the empathy and respect of Bielefeld’s image—are […]