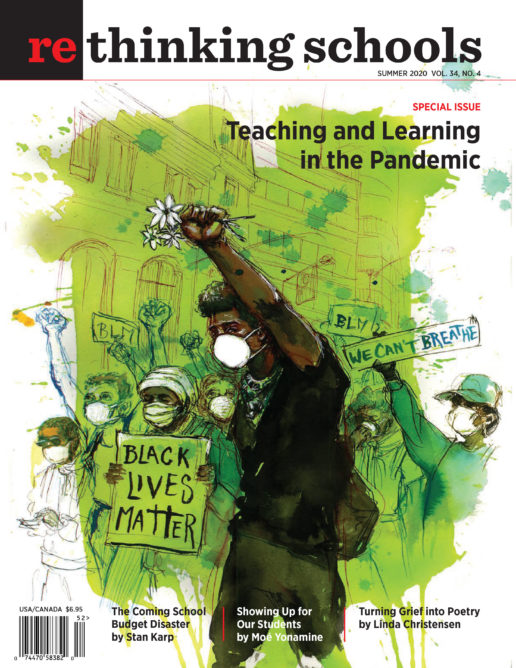

The Fight of Our Lives

Schools and the Pandemic

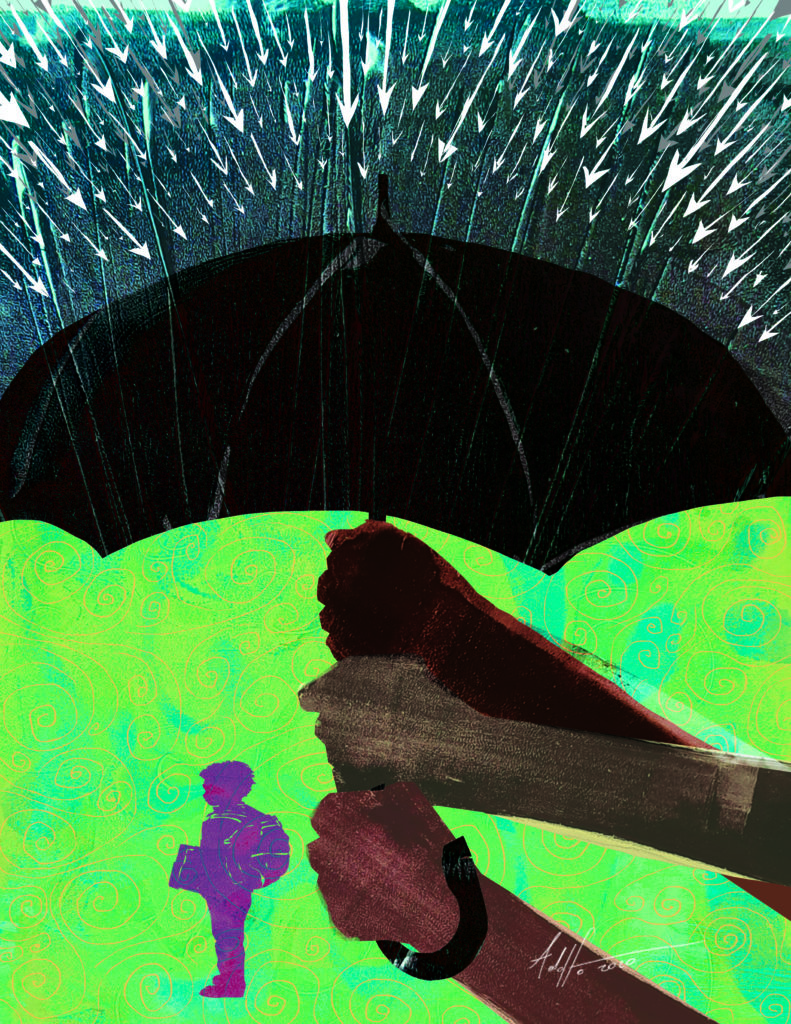

Illustrator: Adolfo Valle

This has been a year like no other. Fear. Illness and death. Trauma for our students, their families, their communities — and for us, as educators.

We are becoming new teachers, new teacher educators, new parents — the pandemic has demanded so much. We moved our curriculum online — no doubt imperfectly and inadequately; schools don’t belong online. We tried to do this work equitably, despite a crisis that is objectively deepening inequality — inequality that schools are not responsible for, and by themselves cannot address. There has been educational accomplishment and creativity, and there has been failure and loss.

As articles in this special issue attest, educators have been nothing short of heroic. Working to connect with their most vulnerable students. Demanding that schools be shut when they became unsafe. Creating and sharing imaginative curriculum. Critiquing wealthy elites’ efforts to exploit this crisis for their own benefit. So this special “Teaching and Learning in the Pandemic” issue of Rethinking Schools is a lamentation, but it is also a celebration — and a call to action.

This special “Teaching and Learning in the Pandemic” issue of Rethinking Schools is a lamentation, but it is also a celebration — and a call to action.

It is hard to imagine that school buildings can reopen in the fall, but when they do reopen, they will need to look drastically different. All sorts of past practices will need to be reassessed. Those who have spent decades attacking public schools and pushing corporate reforms understand this and are ready to swoop in and offer their advice — which often leaves them richer and our schools and communities poorer. A disturbing sign of the potential future came in early May, when New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo announced that he would partner with billionaires, including Bill Gates and former Google CEO Eric Schmidt, to “reimagine education.”

Although imaginative educational work occurred after schools shut down, for most teachers and students, remote learning has meant more stress, more anxiety, and more failure. We reject the push by tech billionaires to make online schools the future of public education. Schools are in-person communities: communal; conversation- and relationship-rich. Schools are where students receive health care and, for many, two meals a day. (When schools first shut down, the immediate question was not “How will children learn?” It was “How will children eat?”) Schools are where students with special needs find community and essential services. None of this can happen in the online “schools of the future.”

It is crucial that in this moment, students, parents, and teachers organize to make our voices heard over corporate executives and Betsy DeVos and her cronies. Therefore, it’s vital that we take the summer to digest and learn the lessons the pandemic teaches.

Since the 1980s, but especially after 2001’s No Child Left Behind Act, the neoliberal project in education has sought to starve public schools of resources and privatize them through vouchers and charters, increase testing and tracking to sort students and measure educational “quality,” and dramatically centralize power over school systems in order to better impose these unpopular initiatives. As billionaires push to double down on these failed policies — and spice them up with not-so-new digital dystopian fantasies — it’s clearer than ever that these plans make it more difficult for public schools to meet students’ needs.

The centralization of power and decision-making in school districts across the country meant that there were few mechanisms, and little desire, to solicit information from students, families, and teachers so schools could prepare to shut down buildings and adequately address the inequitable challenges faced by families whose living spaces had suddenly become workplaces, childcare centers, and classrooms. Instead of schools coordinating and collaborating with families, in most places teachers, parents, and students waited for directives from on high and quickly tried to organize against the worst policies school administrators tried to implement.

One of the most egregious examples was in New York City, the epicenter of the pandemic in the United States, where Mayor Bill de Blasio initially refused to shut schools as COVID-19 spread throughout the city. Teachers threatened sick-outs to force the city to close down school buildings. At several schools where staff had tested positive for COVID-19, the Department of Education kept schools open. This negligence no doubt played a role in spreading the virus and led to the deaths of dozens of school employees by late April. Mirroring the racial and class inequities baked into our society, paraprofessionals, poorly paid and often people of color, made up nearly 40 percent of confirmed cases despite representing only 17 percent of the New York City public school workforce.

But the main argument made for not closing public schools earlier was also revealing. Both Mayor de Blasio and Gov. Cuomo argued that as one of the last public services available to the poor, schools were too important to shut down — families depend on schools for childcare, students rely on the meals they receive, and the more than 114,000 homeless students in New York City rely on schools for showers, laundry, and much more.

Although this argument was echoed across the country, it was amazing to watch the breathtaking speed with which some politicians pivoted from touting the importance of public schools to slashing their budgets. Gov. Cuomo announced in early April that school funding would be drastically cut throughout the state, and New York City proposed cuts to schools and other public services in response to a projected $7.4 billion loss in tax revenue. Indeed, without federal intervention, U.S. school districts are bracing for massive cuts. In his article in this issue [see p. 48 in the print edition], Stan Karp cites an Education Week analysis: “America’s public schools will need $70 billion for three consecutive years in the next round of federal stimulus spending to avoid painful cuts such as teacher layoffs.”

While the economic crisis encourages political elites to ramp up demands for austerity, the public health crisis requires the exact opposite. To reopen amidst a pandemic, schools will need to drastically cut class sizes to maintain social distancing, hire more counselors and nurses to support students’ mental and physical health, give teachers more time to collaborate and give meaningful feedback to make learning relevant in new circumstances, and reduce workloads to give school workers time to reassess past practices and implement new ones. This will require an unprecedented investment in public education. As the $500 billion corporate slush fund passed as part of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act revealed, the money is there, it’s just in the hands of the wrong people.

It is up to us — and to our unions — to demand safety and funding. There will be increasing pressure to return to in-person school in the fall.

It is up to us — and to our unions — to demand safety and funding. There will be increasing pressure to return to in-person school in the fall. Although we know that our students and families deserve in-person learning and community, before this can happen schools need to establish rules, expectations, and parameters for returning safely. We can’t leave this up to district officials and corporate consultants. Teachers and our unions need to articulate the precise conditions under which it is safe for workers, students, and families — especially the most vulnerable — to return, and refuse to go back if those conditions aren’t met.

One silver lining to the pandemic is how quickly states canceled high-stakes standardized tests, revealing to those of us who have fought against these tests how easily they can be eliminated if the political will is there. But at the same time, the inequity that the pandemic has exposed and exacerbated requires an even deeper rethinking of the system that has ranked and sorted students for decades. The San Francisco Unified School District made national headlines when school leaders debated giving all middle and high school students A’s before ultimately settling on a Credit/No Credit grading policy. In Los Angeles, students and teachers organized to ensure no student could fail. What many recognized in this debate that played out in districts across the country is that grades, like standardized tests, have often been indicators of racial and class inequality, and of a student’s willingness to comply with school rules rather than meaningful assessments of achievement.

During the last decade, politicians and corporate executives have vigorously argued that education is the ticket out of poverty, while attacking wages, gutting services, and drastically lowering students’ and families’ standard of living. They have emphasized poverty and lack of success at school as a personal, rather than societal, failure. Many in the school system have internalized this argument and continue to make the case that the best way to teach students about the consequences of their actions and prepare them for the “real world” is to fail them if they do not meet institutional expectations. But as the public health and economic crises deepen inequality, and increase trauma, stress, and anxiety for all of us, it becomes more and more difficult to blame failures on individuals. Every moment of the pandemic teaches all of us — including our students — that the economy values profit over our lives and health. The job of schools in this moment should not be to reinforce this lesson by preparing students to be “good workers,” or obsessing over deficit models like “learning loss,” but instead should help foster compassionate citizens who can strengthen our democracy and make the world more just. Although it seems likely that most districts will return to ranking and sorting through grades and high-stakes testing in the fall, we should heed this lesson and push for a rethinking of assessment as schools navigate this crisis.

The public health crisis demands that we rethink and fight for a different vision of public schools: a less discipline-based, more integrated curriculum; a focus on students’ emotional and physical well-being instead of high-stakes standardized tests; smaller class sizes and workloads where teachers have the capacity to work collaboratively and give meaningful feedback; curriculum that probes inequities and social problems, and inspires curiosity and creativity; democratic decision-making at every level of school governance. The pandemic is likely to reshape the landscape of public education. It is up to us whether that landscape is shaped by billionaires and corporate politicians or by students, parents, and teachers.

Subscribe to Rethinking Schools magazine at rethinkingschools.org/subscribe.