Katrina’s Lessons

Illustrator: Randall Enos

In early September, Hurricane Katrina’s 140-mile-per-hour winds swept through New Orleans and exposed this nation’s underbelly of racial and economic inequality.

As the whole world watched, the waters surged and the levees were breached, leaving a broiling mass of human suffering in the hurricane’s wake. And although Katrina’s damage was overwhelming, much of the devastation in the Gulf came from a slower, more preventable surge of racism and poverty.

A vast number of Katrina’s casualties were poor and black people. As evacuation was left to the free market, those without cars and money were stranded as the floodwaters rose. The disaster laid bare the effects of Bush’s brand of capitalism, which features the privatization of public services. The neglect of the levees, the profiteering of commercial interests, and the destruction of wetlands all helped turn natural disaster into horror.

New Orleans was the shining example of just what the free market could do. Despite a thriving tourist trade, the city’s poverty rate is double the national average, hovering at nearly 30 percent. This means that about 130,000 of its 445,000 residents are poor. The poverty rate for children is significantly higher at 40 to 50 percent. Although firm numbers are difficult to pin down, it is estimated that between 66 and 84 percent of the poor are African American.

Even though the spotlight has been on New Orleans, that city is just a microcosm of what is happening everywhere in the United States. As Nicholas D. Kristof pointed out in his New York Times column, “The Larger Shame Behind New Orleans,” the Census Bureau recently reported that the number of people living in poverty in the United States increased by 1.1 million people from 2003 to 2004. We’ve experienced a 17 percent increase in the number of poor people in the last five years, the fact that the federal government regularly underestimates the number of poor notwithstanding.

For the first time since 1958, the U.S. infant mortality rate has increased, and almost a third of the children in the United States did not have health insurance at some point during the last year.

The neglect of the levees, the wetlands, and ultimately of New Orleans’ residents, is an inevitable by-product of the tax-cutting, infrastructure-starving, war-waging policies that have eroded government capacity and the public sector for several decades. It also represents a foreshadowing of other environmental and social disasters that may await us in an overdeveloped and under-planned economic system.

Katrina’s Children

New Orleans’ schools were also caught up in a flood of racism, poverty, and neglect long before Katrina arrived. There are 60,000 children in New Orleans public schools, and 96 percent of them are African American. Last year, about 10,000 of those children were suspended at one point or another, and almost 1,000 of them were expelled. Half of the high school students in New Orleans don’t graduate.

The district had to borrow money last year to pay the salaries of its teachers. Today, New Orleans’ schools are closed indefinitely and, according to Reuters, 7,000 city teachers and other staff “will not get paid for periods after Hurricane Katrina because there is almost no money left in the city’s strapped school system.”

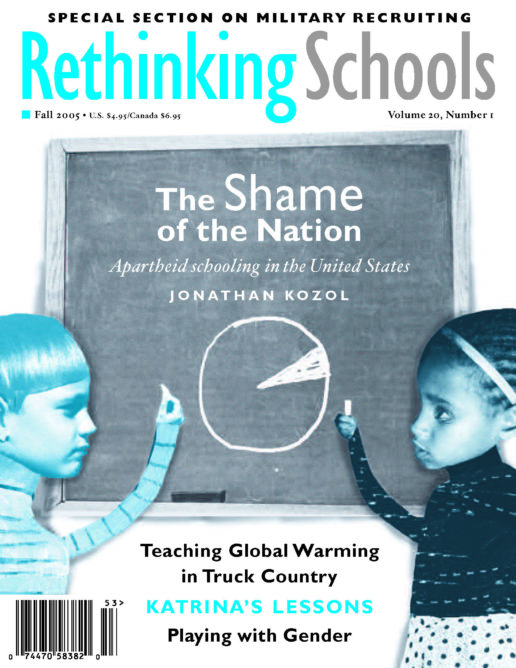

Hyper-segregation, such as that found in New Orleans, means poor children of color receive unequal and inadequate educations. In his new book, The Shame of the Nation: The Restoration of Apartheid Schooling in America [See excerpt], Jonathan Kozol reminds us that our schools are still rife with extreme racial segregation. Children in highly segregated urban schools have worse facilities, lower paid and less-trained teachers and staff, access to fewer classroom and school resources, and are regularly subjected to scripted, dumbed-down curricula. New Orleans is no exception.

Now, according to current estimates, nearly 400,000 students who have been displaced from schools in Louisiana and Mississippi are expected to enroll in schools around the country. According to the Department of Education, at least 28 states and Washington, D.C., are receiving Katrina’s victims. This massive influx of new students into schools, many of which are already struggling under No Child Left Behind mandates, further stretches the meager resources for public education. And at least two of these states, Texas and Utah, propose teaching some of the displaced Gulf Coast school children in shelters rather than in their own public schools.

Consistent with the continual budget cuts, privatization, and overall shrinking of public services, Bush recently announced the allocation of $488 million to help families displaced by Katrina place their children in private schools-specifically those families whose children were already in private schools before Katrina hit. This smells like a back-door approach to get public funding for private schools and would essentially create the first national school voucher plan.

The public sector, which is supposed to serve all people, especially the poor, has been under attack by Bush and his supporters. It is the height of cynicism to turn the failed government response to Katrina, which demonstrated the need to improve and expand the public sector’s capacity to deal with such disasters, into a reason to undermine the public sector-in this case public schools. Why not put that money into the already financially strapped public schools that serve evacuee children?

The federal government’s inability to address poverty in a meaningful way, coupled with its drive to privatize and shrink social services, implies dire consequences for education in this country. As Jean Anyon points out in her book Radical Possibilities [See review, page 54], federal policies around issues such as livable wages, affordable housing, health care, and transportation, play key roles in the educational achievement of children in public schools. The formula is simple: Children with shelter, enough food to eat, health care, and parents who are not forced to work two poverty-wage jobs just to make ends meet, generally do better in school.

There is no silver lining to a disaster like Katrina, but where there is resistance there is hope. In a widely circulated statement, the organization Community Labor United issued a warning: “The people of New Orleans will not go quietly into the night, scattering across this country to become homeless in countless other cities while federal relief funds are funneled into rebuilding casinos, hotels, chemical plants. We will not stand idly by while this disaster is used as an opportunity to replace our homes with newly built mansions and condos in a gentrified New Orleans.” This coalition of progressive New Orleans-area organizations is demanding popular oversight of the rebuilding process and that resources be distributed equitably. [Visit the Quality Education is a Civil Right website, www.qecr.org, to donate to the People’s Hurricane Fund.]

This kind of democratic response is inspiring. We need a similar challenge to apartheid schooling-and all our country’s apartheids: in jobs, health care, housing, and transportation. We need to shore up support for an infrastructure that suffered long before Katrina blew in. As the residents of the Gulf work to rebuild their lives and homes, the need for a strong public sector has become greater than ever-so that this horrific spectacle is never repeated.