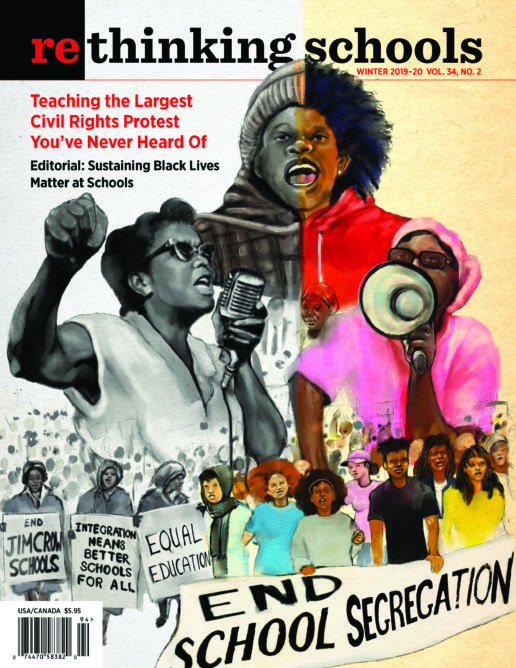

Black Lives Matter at School: From the Week of Action to Year-Round Anti-Racist Pedagogy and Protest

Illustrator: Sharon Chang

Black children are not safe at school.

In September, a “resource” officer at a school in Orlando, Florida, arrested, handcuffed, and fingerprinted a 6-year-old Black girl for throwing a tantrum.

That same month, in the San Juan Unified School District in California, a teacher threw away students’ Black Lives Matter posters.

In October, a cop at a school in New Mexico resigned after a video surfaced of him slamming a sobbing Black schoolgirl to the ground and yanking her arm behind her back — all for the alleged infraction of taking too much milk from the cafeteria.

In November, white parents in Detroit spat on, yelled racial slurs at, and threw garbage at Black football players who took a knee during the national anthem.

These are only snapshots of the daily attacks on Black students.

Beyond these attacks there is the daily curricular violence: the erasure and appropriation of Black struggle, as in the Lincoln-freed-the-slaves myth; the failure of the curriculum to account for the centrality of slavery and anti-Black racism in the shaping of U.S. history, North and South; teaching contempt for Black culture — including African American Vernacular English; and so much more.

Yet despite these attacks on Black youth, an orchestrated backlash to Black Lives Matter at School seeks to silence the voices of anti-racist educators and those who shine a light on the violence — both physical and mental — against our Black students.

Recently, the New York Post gave space to a supporter of racist status quo schooling who attacked the entire Black Lives Matter at School movement as well as two books published by Rethinking Schools — Teaching for Black Lives and The New Teacher Book.

In the attack on Teaching for Black Lives, Peter Meyer wrote:

In the introduction to Teaching for Black Lives, a recently published textbook meant to accompany BLM’s classroom efforts, the first sentence reads: “Black students’ minds and bodies are under attack.”

The stoking of students’ fear and anger continues with a reference to “the continuing police murders of Black people,” along with this characterization of the galvanizing event for BLM’s street protests: “In August of 2014, Michael Brown was killed in the streets of Ferguson, Missouri, his body left in the streets for hours as a reminder to the Black residents in the neighborhood that their lives are meaningless to the American Empire.”

According to Myers, declaring that Black students’ minds and bodies are under attack is a problem because it stokes students’ fear and anger — but the actual attacks on their bodies and minds should go unacknowledged. In his funhouse mirror world, teachers discussing attacks on Black people is more of a problem than the actual attacks.

Nowhere in his article does he mention that in Seattle, where the Black Lives Matter at School movement started, hate crimes have doubled in the last year and risen 400 percent since 2012.

Nowhere does he acknowledge that schools suspend Black students at four times the rate of white students and suspend Black girls at six times the rate of white girls.

Nowhere does he recognize that 1.7 million children go to schools with a police officer but no counselor or the rash of incidents in schools where police officers abuse children.

Nowhere does he discuss the humiliation of Black students being refused entry into school for having dreadlocks — as happened to a 6-year-old Black student in Florida last school year — or a 10-year-old boy in Canton, Michigan, who was charged with assault for playing dodgeball.

Nowhere is it mentioned that many textbooks are Eurocentric and even overtly racist, as the opening lines to Teaching for Black Lives point out with the story of the McGraw-Hill textbook that replaced the word “slave” with “worker,” insinuating that enslaved African people were paid for their labor.

Yet in the face of attacks like these, an uprising for racial justice is growing around the country called Black Lives Matter at School and it is helping to empower students, educators, and families to fight back.

BLM at School began in 2016 in Seattle after John Muir Elementary School educators announced they would wear shirts that said “Black Lives Matter/We Stand Together/John Muir Elementary” — and the school received a bomb threat from a white supremacist. That threat galvanized solidarity and resulted in some 3,000 educators going to school wearing BLM shirts the following month. This action attracted national news, helping it spread to Philadelphia and Rochester, New York.

Philadelphia’s Caucus of Working Educators’ Racial Justice Committee expanded the action to last an entire week, with teaching points around the 13 principles of Black Lives Matter. The following year, organizers around the country took up Philadelphia’s model for the Week of Action, and it grew into a national movement. Last year, thousands of educators in more than 30 cities participated in the Week of Action — including teaching lessons, holding community forums, and organizing rallies in defense of Black lives in education.

The four demands of BLM at School are vital to dismantling institutional educational racism:

1. End “zero tolerance” discipline, and implement restorative justice

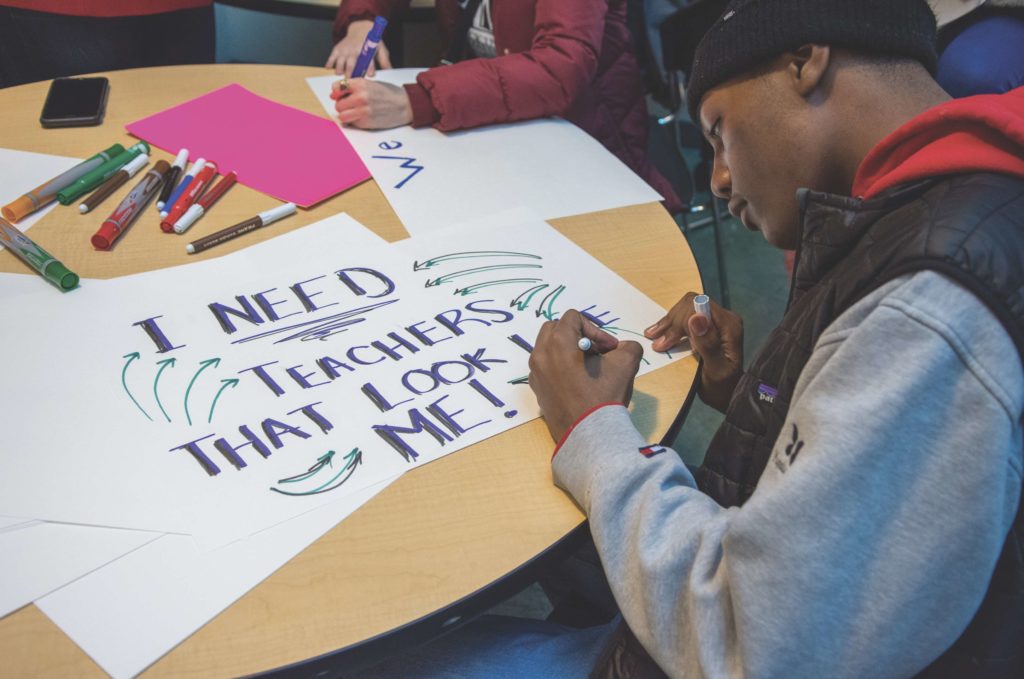

2. Hire more Black teachers

3. Mandate Black history and ethnic studies in K-12 curriculum

4. Fund counselors not cops

The power of the BLM at School Week of Action is its ability to shine a spotlight on these urgent demands. However, we agree with the Week of Action organizers that we can’t confine anti-racist pedagogy or protest to one week or one month — it has to be integrated into the daily practice of educators and schools if we are truly to have an impact.

To this end, we are encouraged by rising actions by students, parents, and educators around the country who aren’t waiting for February to challenge racism and are taking it on whenever they see it.

In September, 10-year-old Promise Sawyers created a viral video where she explained that when she wore her hair in an afro to school in Nashville, Tennessee, “a lot of people had a lot of mean things to say” about her natural hair. But after getting inspiring words from her mother, Qui Daughtery, Promise decided to go back to school with her afro looking bigger and better than ever.

Also in September, Minnesota parents filed a lawsuit against their school district saying its officials failed to respond when Black students endured physical assaults, death threats, and racial slurs, such as being called a “monkey” or “donkey.”

In October, a crowd of Hazel Wolf K-8 students and parents protested outside their Seattle school, calling for the end of the ongoing racist bullying. Aselefech Evans, who chairs the racial equity committee of the school’s parent-teacher association, told the Seattle Times that twice this school year, Black students have been referred to by racial slurs and compared to monkeys by some of their peers. This collective protest is part of a larger plan by the parents and students to change the culture of their school and infuse an anti-racist approach to education.

This year’s Black Lives Matter at School Week of Action holds the potential to ignite more community opposition to educational racism and promises to be the biggest ever.

Educators in the movement are pressing for anti-racist teaching to be integrated in the broader culture of the school and to permeate the curriculum — in social studies, English language arts, math, science, music, art, and beyond.

To support this work, the BLM at School organizers have set up the website www.BlackLivesMatterAtSchool.com, with banks of lesson plans, resources, and a starter kit for those new to the movement.

For educators, it’s not enough to teach about the great social movements of the past, it’s essential to join them today. From educators in Los Angeles and Chicago who raised anti-racist demands in their extended strikes and won important gains for Black and Brown students, to the efforts of many organizations and families around the country struggling against the school-to-prison pipeline, now is the time to get active.

Rethinking Schools believes that every social justice educator should make building the BLM at School Week of Action during the first week of February a top priority — and we offer our solidarity in the fight against racism in schools and the broader society.

Click here to get your copy of Teaching for Black Lives