Nurturing Student Activists in the Time of Trump

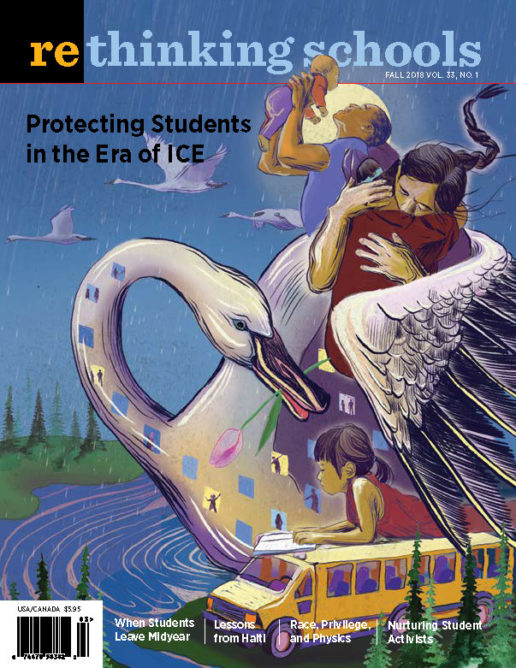

Illustrator: Maggie Chiang

The 2018-19 school year has begun at a time of terrifying climate disruption, seemingly endless war, spectacular inequality, xenophobic and fascist revival, police brutality — and a president fanning the flames of all of the above.

But the year also begins during a renaissance of student activism: around racism and police violence, climate justice, solidarity with immigrants, gun violence, sexual abuse and harassment, and fighting school closures.

So how do social justice educators deepen and support this activism, and seed future activism? How do we equip students to act thoughtfully and effectively? And where are the lines between education and manipulation?

The first way we support student activism is through our curricular choices. Throughout the K-12 curriculum, we want to highlight individuals and movements that challenged injustice, that were grounded in solidarity. We need to make activism common sense. Our curriculum should emphasize that the world becomes more just only when people organize and fight — in the abolition movement, the labor movement, the women’s movement, civil rights and anti-racist movements, antiwar movements.

We should make special efforts to introduce students to young people who worked for justice through collective action — in SNCC (the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee), South Africa’s anti-apartheid movement, the Chicano student blowouts, the anti-Vietnam War movement, etc. Students should learn that these movements were not built by charismatic leaders but by young people like themselves.

And we want to alert students to the young people working for justice today. With breathtaking courage, the Dreamers have helped shape the national debate and fight around immigration. Mexican American Studies students in Tucson and students elsewhere demanding ethnic studies have raised profound questions about whose lives are valued in school curriculum. Black Lives Matter activists raised their fists and voices while building the national movement against police brutality and for criminal justice reform. The Parkland students mobilized school communities across the country as never before to take action on gun violence. Young climate activists, like the plaintiffs in the important Juliana v. United States lawsuit, have put themselves at the center of the fight for their own futures and our planet’s survival. And high school students who are pushing for a meaningful response to sexual harassment, like those featured in Camila Arze Torres Goitia’s “What Students Are Capable Of” (Rethinking Schools Vol. 32.3, Spring 2018), have deepened the #MeToo movement.

This is not the fare for just high school social studies or language arts classrooms. As we wrote last year in our editorial “Little Kids, Big Ideas,” (Rethinking Schools Vol. 31.4, Summer 2017), with younger children, we can help them learn to ask: “Whose story is not being told? What does this look like from a different perspective? What is fair? How can everyone’s needs be met? What can I do?” And as with older students, we can introduce them to “moral ancestors” who stood up for themselves and others, such as the New Orleans 1st grader Ruby Bridges, the first Black child to integrate an all-white elementary school in the South; the young people who marched and went to jail in Birmingham, Alabama’s 1963 Children’s Crusade; and the child workers who in 1913 marched with Mother Jones from Philadelphia to New York City to “show the New York millionaires our grievances.”

Teachers alert children to these currents of activism and justice through stories, picture and chapter books, videos, songs, plays, news articles, and group projects. Elementary reading programs can include an array of nonfiction and historical and realistic fiction in which the main characters are children who work for social, racial, or environmental justice. Teachers in other disciplines can also put activism for justice at the center of the curriculum. See for example, the chemistry teachers who organized a schoolwide “Climate Justice Fair,” described in this issue’s “Earth, Justice, and Our Classrooms” column.

It also matters how we present these stories. We need a pedagogy of respect, and active participation — a people’s pedagogy that mirrors the people’s history of social movements at the center of our teaching. Our curriculum should feature role plays in which students confront the difficult choices that actual organizers confronted, improvisations that bring to life the day-to-day interactions that add up to social change, mixers that alert students to a multiplicity of perspectives on a particular issue. Our pedagogy should help students develop skills they’ll need beyond the classroom — how to run a meeting, how to construct an argument, how to deal with disagreement among peers.

We need a “show, don’t tell” pedagogy that underscores the message that people make history. This kind of teaching insists that students learn through participation, not by absorbing knowledge from the authority of the teacher, a pedagogical ritual that reinforces intellectual passivity and an uncritical acceptance of the status quo.

Some of this work will take place in formal classroom settings, but we can also provide space and time outside of class hours for students to meet about issues that concern them. Elementary student clubs we are familiar with have included Students Against the War, Students Against Child Labor, and Students to Save the Librarians. In Milwaukee, high school teachers have volunteered to be advisors for groups like Youth Empowered in the Struggle, the youth affiliate of the community organization Voces de la Frontera.

But not all activism is equal. We need to help students distinguish between description and explanation of injustice, so that our classroom inquiry identifies root causes and not only symptoms. Corporate hucksters are eager to deflect activism toward individualistic, consumer models of addressing social and environmental ills — take shorter showers, recycle, don’t be a litterbug — rather than toward the deep systemic foundation of injustice. This conservative orientation shows up in too many textbooks and mainstream curriculum. The deeper and more precise students’ analysis of social wrongs, the more profound their activism will be. Imagining real solutions connects to understanding the fundamental causes of grievances. That means giving students the tools to weed through and name multiple and interlocking systems of oppression. And our curriculum should be internationalist, so that students see how struggles here connect to others around the world — and that allow students to learn how social movements from Okinawa to Haiti identify and organize to address their grievances.

At the same time, a classroom is different from an organization. Students are attending public schools, not joining an activist group. And sometimes the lines between equipping students to imagine themselves as activists, and directing their activism, can be a blurry one. We want to empower and encourage, but not to direct or “lead.” In a time of resurgent student activism, including student walkouts, teacher participation in actions can show respect for student initiative and teach important lessons about how change happens. But teachers should also be careful not to impose their own ideas, which can stifle independence and silence diverse perspectives in the classroom.

That said, one recurring feature of established authority’s response to student activism is to charge that their activism is phony, the product of teacher and adult manipulation. When, for example, students in Tucson organized to defend that school district’s outstanding Mexican American Studies program in 2011, Tucson Superintendent John Pedicone was incredulous that students themselves could plan and execute a school board occupation and articulate demands. In the Arizona Daily Star, Pedicone wrote that the students “have been exploited and are being used as pawns to serve a political agenda.” According to the then-superintendent, Tucson students “are being used to lead the charge for those who wish to make this a civil rights issue” — as if students were incapable of recognizing that the character of their education is a civil rights issue.

In apartheid South Africa, the idea of the “outside agitator” stirring up students became an article of faith for the white minority regime. During the 1986 State of Emergency, authorities even forced students to carry IDs to school so they could detect who was an actual student and who was an alleged manipulating adult. Students responded by throwing their IDs into bonfires.

The point is that when we help seed student activism and teach with a language of justice and defiance, defenders of the status quo will often label us as puppeteers, controlling student activism. It’s another sign of disrespect by people in power of students’ capacity to question, to think critically, and to take action for what they believe is right.

So it’s vital to be self-aware and make sure that we respect our students’ integrity as thinkers and actors, and not substitute our priorities for theirs. But that doesn’t mean that educators cannot have a curriculum that itself reaches outside the classroom and gives students opportunities to exercise their moral and political sensibilities. In fact, it’s only through helping students come to see themselves as activists that we can help defend young people from the cynicism about the prospects for a better world that is so prevalent. For example, the resolution that activists — including students — got the Portland Public Schools school board to pass about how schools should respond to the climate crisis says: “All Portland Public Schools students should develop confidence and passion when it comes to making a positive difference in society, and come to see themselves as activists and leaders for social and environmental justice.” That should be an aspiration for all educators.

Having a school district resolution touting the importance of activism is wonderful. But it’s educators who make the critical difference. Beyond the classroom, teachers set an important example for students when we engage in activism. It was educators, in collaboration with community members, who led the inspiring Black Lives Matter at School day of action on Oct. 19, 2016, in Seattle. Staff members throughout the district wore Black Lives Matter solidarity T-shirts to school and sponsored events and classroom activities throughout the city. (See “How One Elementary School Sparked a Citywide Movement to Make Black Students’ Lives Matter,” by Wayne Au and Jesse Hagopian, Rethinking Schools Vol. 32.1, Fall 2017.) This was an instance of teachers creating an activist context that had a huge impact on students. As one Garfield High School senior, Bailey Adams, told a TV news reporter: “There was a moment of like, is this really going to happen? Are teachers actually going to wear these shirts? All of my years I’ve been in school, this has never been talked about. Teachers have never said anything where they’re going to back their students of color.”

How we seed and support student activism will vary from community to community, school to school, and grade level to grade level. But this is a crucial moment in history, and what we do as educators matters. When we help students explore and analyze exploitation, injustice, and danger in the world, we can also help them develop the knowledge and skills to change it.