Teaching More Civics Will Not Save Us from Trump

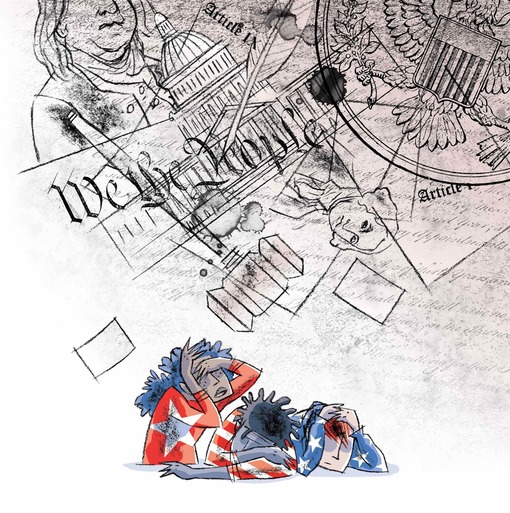

Illustrator: Christiane Grauert

Working as a social studies teacher for almost two decades, I have noticed a predictable and perennial pattern. A study is published showing some alarming deficit in the knowledge of people in the United States. Two-thirds of respondents cannot find Iraq on a map. One-third cannot name a single right protected by the First Amendment. More people can accurately identify Michael Jackson as the artist behind “Billie Jean” than can identify the Bill of Rights as amendments to the Constitution. And each time one of these gobsmacking studies is published there is an equally predictable response: Why aren’t kids learning this stuff in school?

Cue the calls for reform: “a return to the basics,” stricter standards, high school exit exams, more civics education.

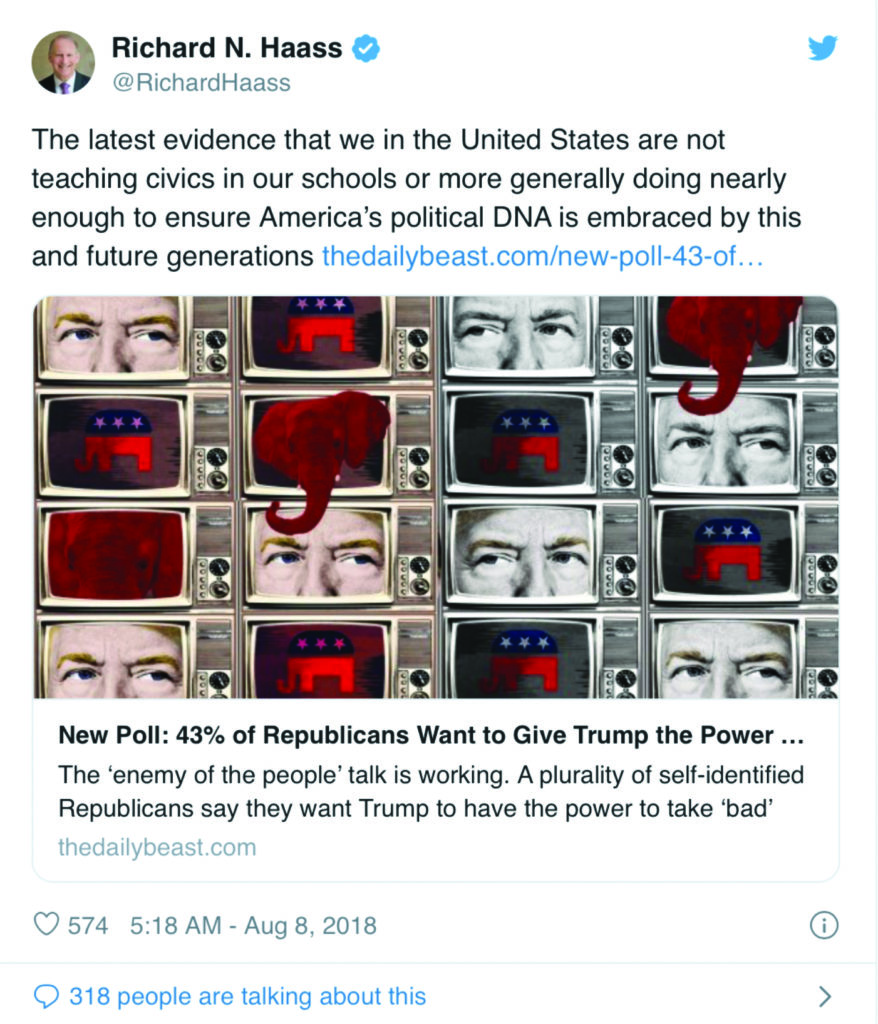

For example, not long ago, Ipsos reported that 43 percent of self-identified Republicans say that “the president should have the authority to close news outlets engaged in bad behavior.” Some analysts saw in this data evidence that President Trump’s “enemy of the people” refrain is working to erode public confidence in the news media. But others sounded a different and familiar alarm. Here, below, is Richard Haass, the president of the Council on Foreign Relations, on Twitter.

These poll numbers are terrible; and this political moment is unquestionably an emergency demanding resolute action in every corner of U.S. life, including schools and curriculum. So although I wholeheartedly support Haass’ suggestion that students need civics, I wonder what kind of civics?

Haass says children in the United States are not being taught civics. But what if he has it wrong? What if it is not the absence of civics that is the problem, but its standard, default iteration? Too often, our curriculum teaches the Constitution as if it is a holy text (with the framers its prophets). It asks students to memorize what is legal more often than it asks them to grapple with what is just, and privileges the mechanics of political institutions over the social movements that can transform them. It is a curriculum that tells students the meaning of citizenship rather than inviting them to be authors of its ongoing definition and redefinition. Not surprisingly, this is a civics education that can be standardized and tested, adding yet more millions into the corporate textbook and testing industries. So I enthusiastically endorse more civics, but it cannot be more of the same.

And what of Haass’ suggestion that the goal of civics education is to “ensure America’s political DNA is embraced by this and future generations”? One hopes Haass is not beseeching children to “embrace” land theft, genocide, slavery, and the disenfranchisement of women and people of color. Yet there can be no honest study of the U.S. political DNA absent those reprehensible strands in its helix. Haass’ use of the verb “embrace” romantically alludes to something pure and uncomplicatedly good in our collective past. But there is no pristine moment — no uncontaminated DNA — to which we can return to escape the evil of the present; indeed, the white supremacist, nativist, misogynist language we have heard spill from the lips of Donald Trump resonates with the 39 percent who steadfastly support him precisely because it has deep roots in U.S. history and politics.

If not more of the same civics education we’ve seen recycled for decades, nor more of the sort suggested by Haass’ idealization of the nation’s “political DNA,” then what? The civics we need more of provides students a clear-eyed understanding of U.S. founders and foundations, free of mythology and hagiography. It surfaces the lives and experiences of groups historically denied voice and power in U.S. politics: women, the enslaved, Indigenous peoples, immigrants. It highlights activism — not just institutions or heroic individuals. It acknowledges that although our “political DNA” has never been worthy of a full, unqualified embrace, abolitionists, feminists, and labor organizers established a tradition of activism that is. It enjoins young people — and all of us — to act against injustice, providing historical and current examdples of what that looks like. This is the civics I want more of.

*** Get more articles like this by subscribing to Rethinking Schools ***

In my social studies classroom over the years, civics has often meant incorporating lessons and resources from the Zinn Education Project, which Rethinking Schools coordinates with Teaching for Change. ZEP is dedicated to helping teachers teach a more accurate, complex, and engaging history than what is found in most textbooks. For example, with my students, civics has meant investigating the United States’ “political DNA” in a role play by Rethinking Schools curriculum editor Bill Bigelow that upends the traditional narrative of the Constitutional Convention by including the perspectives of workers, enslaved people, and poor farmers, alongside those of the real participants — the white wealthy elite. There is no “civics education” that does not begin with the understanding that white supremacy is a fundamental component of our founding documents. The Constitution was not a document to promote democracy, but to prevent it. Through the Constitution Role Play, my students engage in an activity where they see this unfold in the classroom.

Civics has meant teaching the role of tribal sovereignty — and its suppression — in the “political DNA” of the United States in a lesson about the Cherokee and Seminole Nations confronting the Indian Removal Act of 1830. Students see how the naked racism and greed of Southern whites found expression in Andrew Jackson’s presidency and led to the Trail of Tears, and the death of perhaps a quarter of the Cherokee people. And in a role play I co-wrote about the Dakota Access Pipeline, students bring to life this long-standing conflict between Indigenous rights and settler colonialism.

Civics has meant reminding students that for most of the history of this country, excluding marginalized groups from the franchise was part of its “political DNA,” for example, by investigating the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention, where even the first U.S. gathering of women to demand their rights as women failed to include Indigenous women, African American women, working-class white women, or women from lands recently seized from Mexico. Similarly, my version of civics education has meant highlighting the Black struggle for voting rights during Reconstruction, 100 years later, and today — to see how this country’s history is not a neat pageant of progress, but has always been characterized by struggles for racial equality and attempts to maintain white supremacy.

Civics has meant equipping students to understand that from its founding, the United States has aspired to empire. Students examine James Madison’s arguments in Federalist Papers #10 that the Constitution establishes a republican — rather than democratic — form of government to allow for and promote expansion. No matter how it has been prettied up in textbooks with terms like the Louisiana Purchase or the Mexican Cession, or romanticized in the Oregon Trail, the “political DNA” of this country includes the military takeover of the lands of people of color and the expansion of the United States of America. And it has meant asking my students to look for patterns in U.S. history to explain recent and current military interventions, from Guatemala to Vietnam to Chile to Iraq.

Finally, civics has meant challenging students’ unquestioning faith in our “political DNA” by introducing them to times when, if not for whistleblowers and lawbreakers, the unconstitutional use of state power would have proceeded unchecked, like the FBI’s war on the Black Freedom Movement and “The most dangerous man in America,” Pentagon Papers whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg. Teaching “civics” means alerting students to the fact that every expansion of freedom and democracy in our country is the product of activism and organizing, of civil disobedience, of people enacting Frederick Douglass’ prophetic words, “If there is no struggle, there is no progress.”

Yes, let’s teach civics. But let it be a civics that arms our students with an honest account of our nation’s political DNA, so they may have the wisdom to actively transform it into one worthy of our embrace.