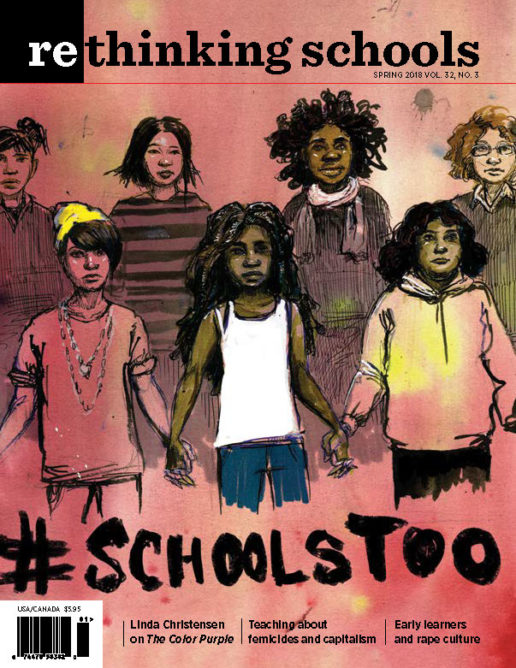

#SchoolsToo: Educators’ Responsibility to Confront Sexual Violence

Illustrator: Sally Deng

Tarana Burke sparked the #MeToo movement more than 10 years ago to speak out against the sexual violence she experienced and to bring healing to the young women of color she works with at Girls for Gender Equity. In a Democracy Now! interview, Burke said, “‘Me Too’ was about reaching the places that other people wouldn’t go, bringing messages and words and encouragement to survivors of sexual violence where other people wouldn’t be talking about it.”

One of those places is schools. The ongoing, persistent verbal and physical violence against women, youth, and LGBTQ communities has not been adequately addressed in most schools. Instead of educating children and youth about gender equity and sexual harassment, schools often create a culture that perpetuates stigma, shame, and silence. Student-on-student sexual assault and harassment occurs on playgrounds, in bathrooms and locker rooms, on buses, and down isolated school hallways. Students experience sexualized language and inappropriate touching, as well as forced sexual acts. And they encounter these at formative stages of their lives that leave scars and shape expectations for a lifetime. What isn’t addressed critically in schools becomes normalized and taken for granted.

When a few Rethinking Schools editors gathered together with early-career teachers over winter break, stories spilled out. One teacher told about a high school girl sexually assaulted on a school bus, with witnesses, including the bus driver and a videotape, but nothing happened to the perpetrator. These kinds of assaults on young women and LGBTQ students sparked a backlash at Madison High School in Portland, Oregon, according to Camila Arze Torres Goitia, (p. 8) where 120 students held a day-long Restorative Justice Circle demanding the school and district create and enforce a sexual harassment policy. But as Zanovia Clark poignantly discusses in “‘How Could You Let This Happen?'” (p. 14), these incidents begin much earlier.

Although few schools have adequately addressed sexual harassment and sexual violence, we still believe that schools are the best places to educate students about these issues because they house the population most likely to be both victims and perpetrators of assault.

Sexual harassment and sexual violence are systemic problems that demand structural and curricular changes in our schools. Schools need to move beyond the click-through online sexual abuse trainings for staff and have real conversations, discuss dilemmas that illuminate both contemporary and historical issues, and work together to create curriculum to address the problems. Because some teachers and administrators have grown up in families and cultures where males dominate and sexual abuse and harassment have been tolerated, many are unclear about what constitutes sexual violence. Just as racial stereotypes and attitudes develop at a very young age so do sexist attitudes. Too often, faculty, administrators, and students are oblivious to the culture of male domination that provides the soil for assaultive sexual misbehavior.

For example, two early-career teachers we know noticed the toxic masculinity in their high school. During a faculty meeting, they tallied the number of times men spoke compared to the times that women spoke. After taking notes in one meeting, they stopped counting, because talking over and crowding out women’s voices was so rampant. This one action — a tally — points toward the larger issue of silencing students and faculty who fear coming forward or whose allegations are treated as tattling or rumors. But what these teachers noticed also illustrates the prevalence of male voices and perspectives in the curriculum, the faculty room, and in district offices where decisions are made.

Unfortunately, there’s a brotherhood of silence that allows predators to continue to abuse children and adults. Both official and informal strategies of denial feed this culture of silence. Institutions seek to suppress damaging information. Nondisclosure agreements allow predators to buy silence from victims. Shaming campaigns and “codes of silence” shut down investigations. These are all reasons why schools need pro-active policies and open discussion of norms and consequences in place of reactive damage control. Schools reflect the sexist culture around them and that sexist or harassing behavior among faculty and administrators often sets the backdrop for similar patterns among students.

In one school district, a teacher’s file of sexual abuse allegations dated back almost 20 years. A student, who told police about the teacher’s actions in 2001, said that having adults discount her story undermined her sense of self-worth. “I must not have mattered enough,” she said. “I sure as hell didn’t feel protected by anybody.” Years later, after middle school girls intentionally wore shoes inappropriate for gym so they didn’t have to go to this teacher’s PE class, the school wrote that these girls’ allegations against him were “rumors.” He wasn’t fired until a male administrator filed a complaint against him.

How do we create schools that nurture both safe and educational spaces? School districts must act in multiple areas. Quality curriculum and staff development is necessary on a range of topics from sexual harassment and abuse to growth and human development to anti-bullying. Such teaching should be in the context of a broader retooling of school curriculum, textbooks, and practices so that issues like sexism, gender equality, and the history of struggle for women’s and LGBTQ rights are woven through all subject areas and grade levels.

To combat the misogynist culture, parents and educators have to disrupt sexist gender roles and the objectification of women that feature prominently in advertisements, TV, and movies. Young children absorb the sometimes subtle, sometimes not-so-subtle, sexist and patriarchal, oppressive attitudes from car commercials, comments of older siblings, a grandparent’s gendered remarks, a catcall from an unknown male in a public place, a Barbie doll, and the left-out history, literature, and accomplishments of women.

Most discipline policies need revamping to adequately address these issues. When situations occur — from disrespectful hallway comments to bus harassment to coerced oral sex in the back halls — instead of sweeping the charges under the rug and pretending nothing happened, schools need policies in place that both exact justice and promote education. As we see in Clark’s article, her school punished boys for groping a girl, but never addressed the behavior as a problem of schoolwide culture or educated the boys about the nature of their wrongdoing. Of course, perpetrators need to understand and be held accountable for their actions, but schools also need to acknowledge that these youth are members of a society that often teaches unhealthy practices around sexuality. Who else will disrupt these misogynistic practices and ideas?

Other school policies should also be reviewed with these issues in mind. For example, dress codes often single out girls for wearing “distracting” clothing. In her Rethinking Schools article, “Girls Against Dress Codes,” Lyn Mikel Brown [Volume 31, No. 4 — Summer 2017] discusses young women who created a feminist club and took on the administration’s dress code that forbade them from wearing shorts and shirts with spaghetti straps. “After reasoned conversation with administrators failed, club members quietly posted dozens of 8.5″ x 11″ sheets of white paper with large black print on school bulletin boards: ‘Instead of publicly shaming girls for wearing shorts on an 80-degree day, you should teach teachers and male students to not overly sexualize a normal body part to the point where they apparently can’t function in daily life.'” As Brown points out, schools suffer from a sexist vision of the world that finds its way into school culture, curriculum, and policies:

Dress codes are a stand-in for all the ways girls feel objectified, sexualized, unheard, treated as second-class citizens by adults in authority — all the sexist, racist, classist, homophobic hostilities they experience. When girls push back on dress codes they are demanding to be heard, seen, and respected. This means it’s a moment primed for intergenerational engagement and education.

As Brown points out, we need a reconstruction of schools that looks critically at our curriculum and asks, “Who counts? Whose voices are heard, whose history is studied? Whose literature is read?” Schools need a curriculum that takes women’s lives, voices, struggles, and accomplishments out of the margins and into the center.

When Linda Christensen (“#MeToo and The Color Purple,” p. 24) worked with school districts and asked members of high school language arts communities to make a list of each book they taught by grade level and then to note the gender and race of the main characters and authors, every single school district discovered that during their four years of high school language arts, students rarely encountered main characters or novels by women, writers of color, or from LGBTQ communities. If we reconceive schools by bringing women in from the margins, educators in every subject area should conduct similar inventories asking: Where are the women scientists, historians, labor organizers, mathematicians, artists, dancers, choreographers?

And of course, schools should teach about the rich tradition of feminists who have fought directly against women’s political, social, and economic oppression. Students need to learn about the historic Seneca Falls conference, which Bill Bigelow’s role play at the Zinn Education Project website both celebrates and troubles for its lack of economic and racial diversity. Students need to learn about the role of women in both the Abolitionist Movement and the Civil War. Students need to know how the women in the Civil Rights Movement — Ella Baker, Septima Clark, Fannie Lou Hamer — created grassroots campaigns for equality. Students should study the intersection of Indigenous rights, treaties, and contemporary climate justice issues by learning about the women-led Idle No More movement to stop the desecration of the land. And students should learn about both the femicides on the border that Camila Arze Torres Goitia and Kim Kanof describe in their article, “Young Women Like Me” and the ways people have resisted through art, poetry, and organizing.

Schools need to recreate both classrooms and faculty rooms with a vision that includes opening spaces for students and teachers to learn from each other through writing and telling stories from their lives. This vision would prize listening over talking, empathy over indifference, collaboration over competition, activism over compliance. We need a curriculum that honors activists and those who interrupt injustice. In addition to pinning awards on competitive sports teams, let’s create awards for the whistleblowers, the truthtellers, the students who investigate, stand up, walk out, protest. Let’s nurture schools as places where addressing such issues as sexual equality and respect are considered vital priorities rather than bothersome distractions.

In her poetic tribute to her mother’s accent, a “sancocho of English and Spanish,” the poet Denice Frohman wrote,

there is no telling my mama to be “quiet,”

she don’t know “quiet.”

her voice is one size better fit all

and you best not tell her to hush,

she waited too many years for her voice to arrive

to be told it needed housekeeping.

For too long schools have silenced the voices of children who have been sexually abused, hazed, or shamed. For too long, the curriculum smothered the voices of women and LGBTQ communities, their writing, and achievements. Like Denice Frohman’s mother, our students’ voices and lives don’t need “housekeeping”; they don’t need to be “hushed.” Young women and girls need to be given the authority to speak out. They need a curriculum and a school culture that unleashes their capacity to envision a world that nurtures instead of competes, that cooperates instead of dominates.