Reconstructing Race

This content is restricted to subscribers

This content is restricted to subscribers

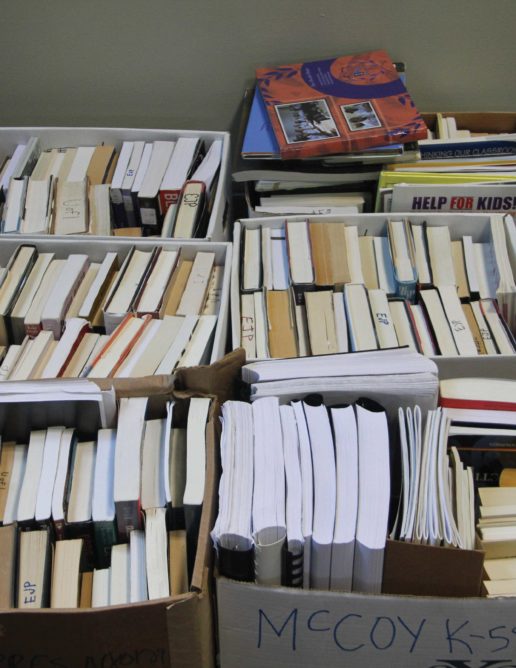

In late January, authorities at the Danville Correctional Center in east-central Illinois removed more than 200 titles from the prison’s library. One of the books that was confiscated was the Rethinking Schools book Rethinking Our Classrooms: Teaching for Equity and Justice, first published in 1994 and edited by Bill Bigelow, Linda Christensen, Stan Karp, Barbara Miner, and Bob Peterson.

A 3rd-grade teacher uses thousands of pieces of macaroni to facilitate a lesson about fractions and to spur classroom conversations about wealth inequality.

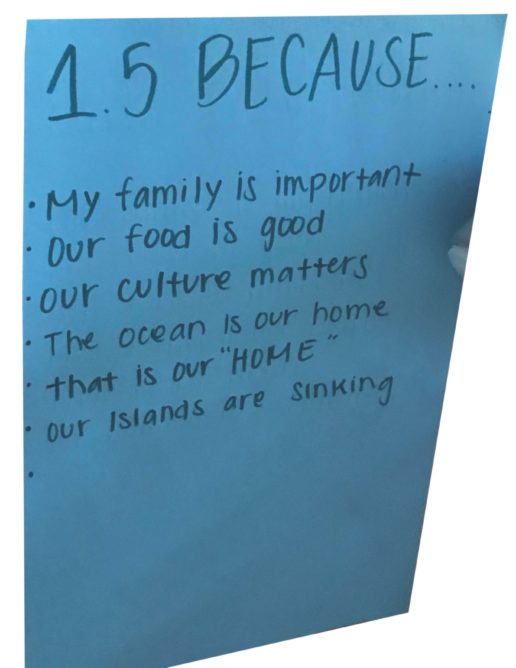

A high school ethnic studies teacher describes how students in the Pacific Island Club used poetry to refocus the narrative surrounding climate justice onto frontline communities.

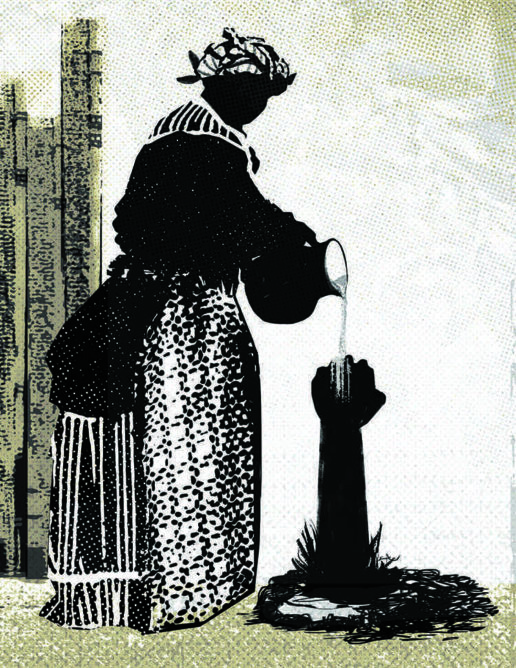

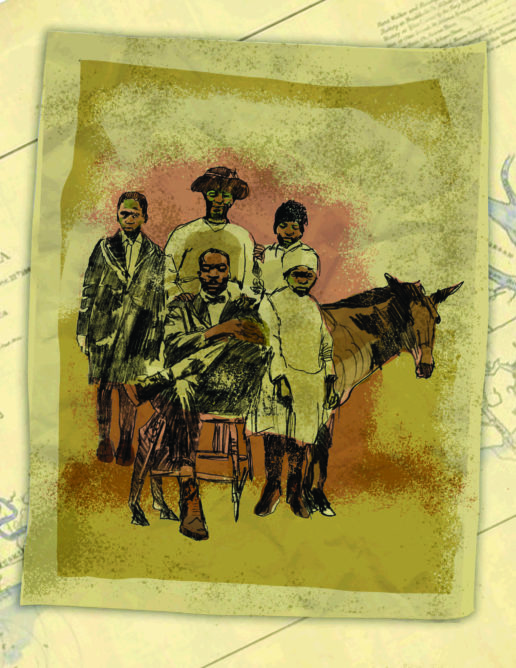

Unfortunately, the transformative history of Reconstruction has been buried. First by a racist tale masquerading as history and now under a top-down narrative focused on white elites. It’s long overdue we unearth the groundswell of activity that brought down the slavers of the South and set a new standard for freedom we are still struggling to achieve today.

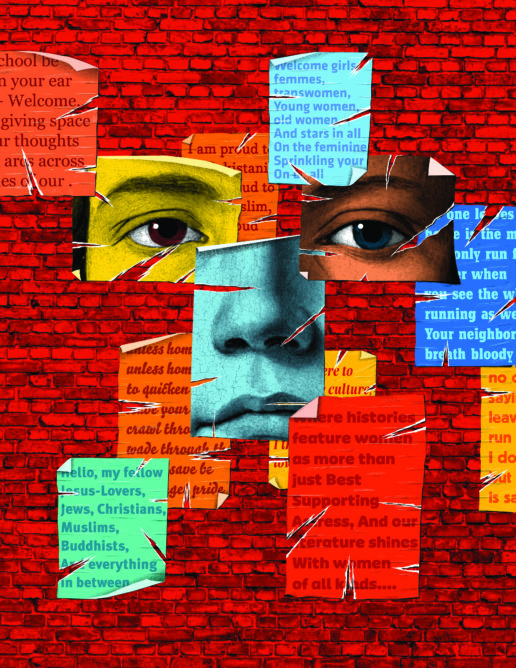

Students’ names are the first thing teachers know about the young people who enter our classrooms; they can signal country of origin, gender, language. Students’ names provide the first moment when a teacher can demonstrate their warmth and humanity, their commitment to seeing and welcoming students’ languages and cultures into the classroom.

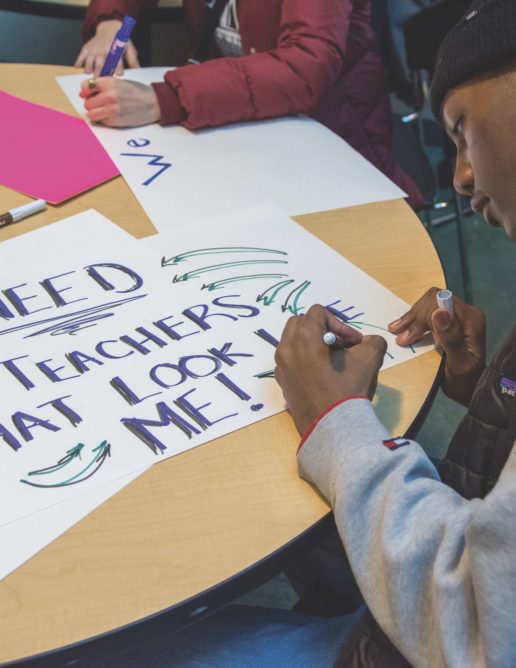

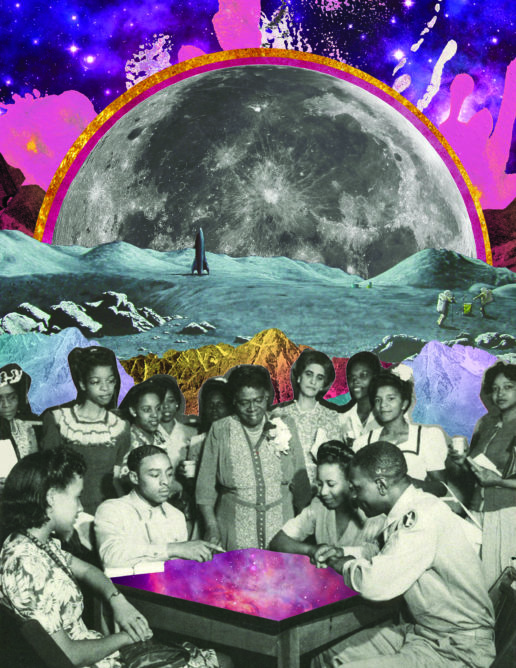

In an era when a U.S. president calls Haiti and African nations shithole countries; a time when hate crimes are on the rise; a time when Black students are suspended at four times the rate of white students; and a time when we have lost 26,000 Black teachers since 2002, building a movement for racial justice in the schools is an urgent task. Black lives will matter at schools only when this movement becomes a mass uprising that unites the power of educator unions and families to transform public education.

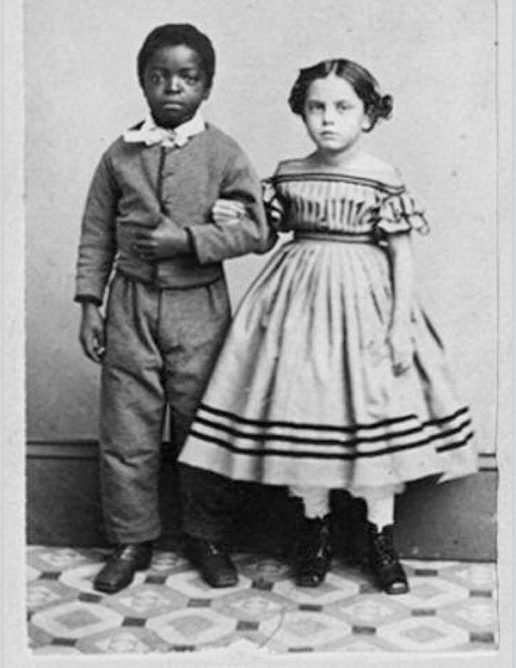

A high school teacher uses a role play so students can imagine life during Reconstruction, the possibilities of the post-Civil War era, and the difficult decisions that Black communities had to wrestle with.

A teacher-educator describes how she keeps her students talking about race, even when it’s uncomfortable — and shows how those conversations make better teachers.

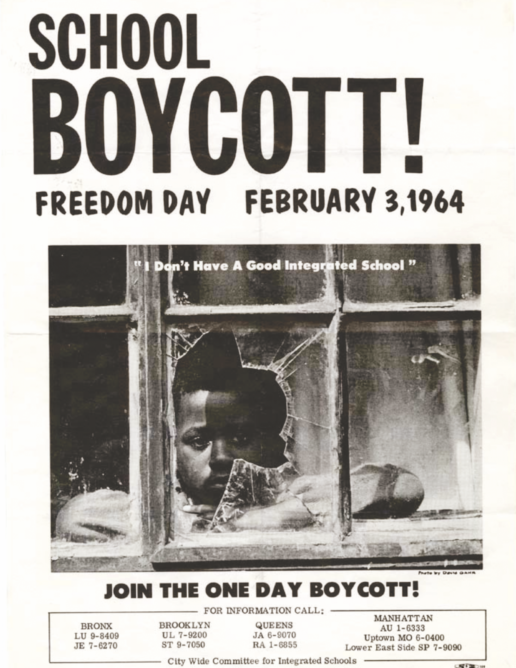

The largest civil rights protest wasn’t in the South, it was in New York City in 1964 when hundreds of thousands of students stayed home to protest school segregation. Here’s how today’s students reacted to a lesson about this historic boycott.

Every social justice educator should make building the BLM at School Week of Action during the first week of February a top priority.

A teacher creates a welcome poems lesson to celebrate the diversity of students — and with students.

We asked a group of radical educators to weigh in on what they hoped would be part of any 2020 presidential candidate’s education platform.

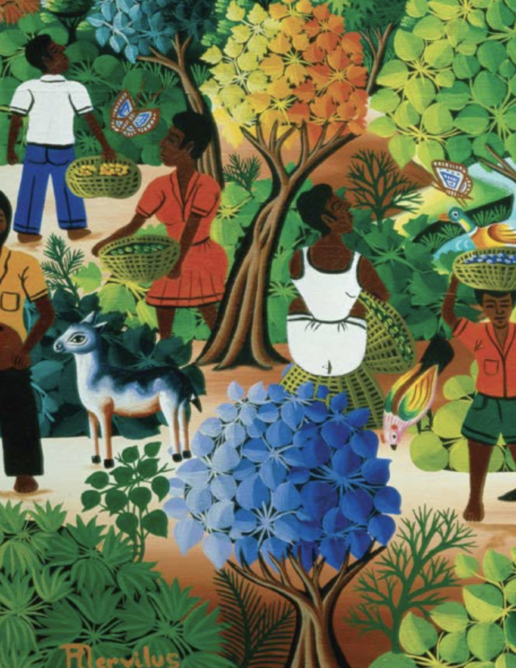

“Haiti is one of the poorest countries in the world.” That’s the only thing this Haitian American teacher remembers being taught in school about her family’s country of origin. She calls for a revolution in how educators teach Haiti.

A physics teacher uses student research and other exercises to urge his high school class to wrestle with race, privilege, and representation.

How 4th-grade students in Southern California were helped by their teachers to develop curriculum surrounding the mass deportation of U.S. citizens of Mexican heritage in the 1930s and pass a law to investigate what happened.

Right away I recognized her. Ruby Bridges. The courageous girl who defied white racists and became the first to integrate an all-white elementary school. My 7-year-old son pulled a handout out of his backpack with her face on it. He is in a bilingual, two-way immersion program at our local elementary school. As is our custom on Friday, we emptied his backpack and sorted the contents. We determined what needed to be recycled, what would be hung on our whiteboard, and what needed to be stored in my Things-to-take-care-of box by the fridge. I smiled, because as a former history teacher and lover of Black history, I was happy to see my son learning about this important historical moment. And then, I took a closer look and saw that it was in Spanish. I was elated as it dawned on me that my son truly is emergent bilingual. “Caleb, what’s this about? Did you read this in school?”

A first-year teacher struggles with what it means to be a social justice educator.

Trump supporter Carl Paladino’s racism, misogyny, and transphobia galvanized community members to oust him from the Buffalo School Board. Their struggle also laid the groundwork for new coalitions and progressive change.

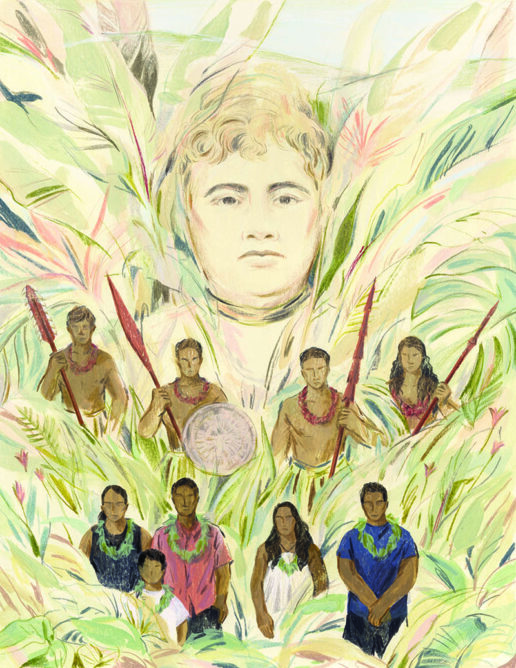

A high school teacher uses the #MeToo movement and students’ own experiences with apologies to interrogate the government’s 1993 apology to Native Hawaiians for the 1893 overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawai’i.

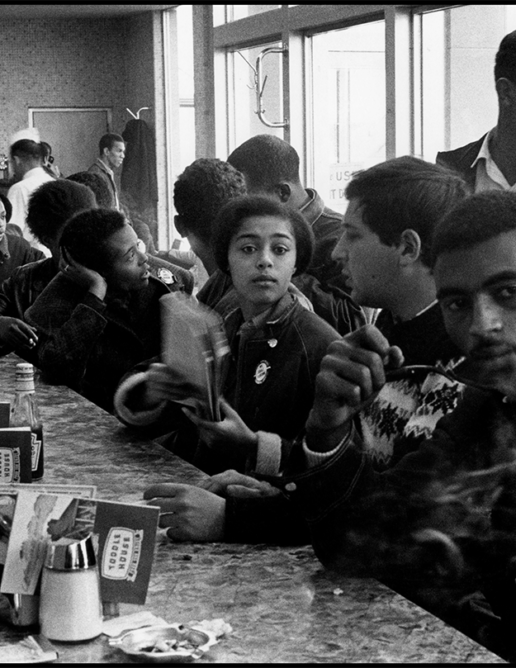

Teaching the history of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee helps students see the Civil Rights Movement as being fueled by thousands of young people like themselves instead of a few charismatic leaders. “Without the history of SNCC at their disposal, students think of the Civil Rights Movement as one that was dominated by charismatic leaders and not one that involved thousands of young people like themselves. Learning the history of how young students risked their lives to build a multigenerational movement against racism and for political and economic power allows students to draw new conclusions about the lessons of the Civil Rights Movement and how to apply them to today.”

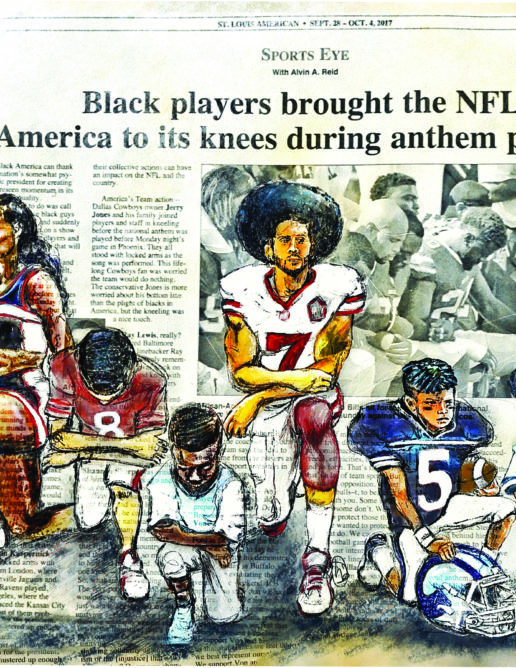

In the initial weeks of the 2016 football season, as Kaepernick’s fledgling protest began to take shape, critics bombarded him with insults and it was unclear what the response around the country would be. And that’s when Garfield, and high schools and students around the nation, stepped up to the challenge.

The increasing violence against Muslims, Sikhs, South Asians, and others targeted as Muslim, suggests we, as Americans, are becoming less tolerant and need educational interventions that move beyond post-9/11 teaching strategies that emphasize our peacefulness or oversimplify our histories, beliefs, and rituals in ways that often lead to further stereotyping.

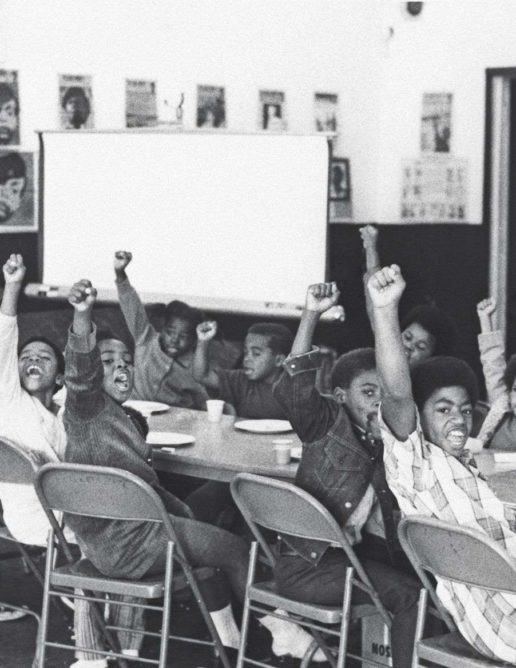

The history of the Black Panther Party holds vital lessons for today’s movement for Black lives and all movements to confront racism, inequality, and police violence. But our textbooks distort the significance of the Panthers — or exclude them completely.

A victory for ethnic studies in Arizona.