Honor Their Names

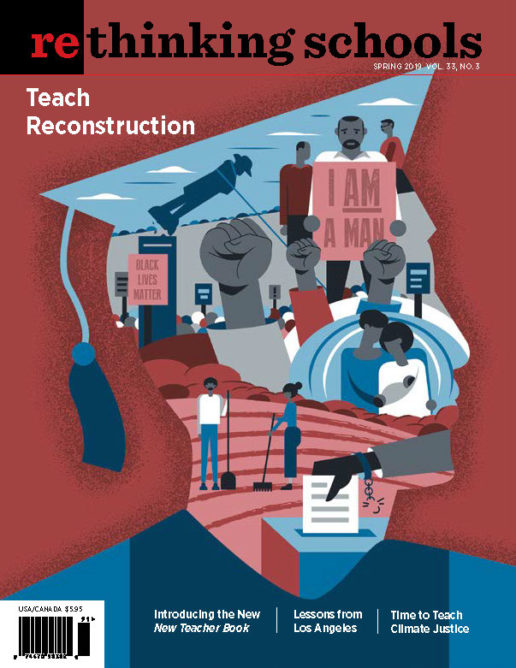

Illustrator: Simone Shin

At a sports bar in British Columbia, a gracious and gregarious young woman seated us. As we slid across the bench in the booth, I asked her name. “Carol,” she said.

“Carol,” I repeated. “My name is Linda. We have names from a different generation.”

She laughed. “Oh, my real name is Chichima. Carol is my white name. My family is from Nigeria, so when we immigrated, I changed my name at school. It’s easier for the teachers. We all have white names.”

“Why is that?” I asked.

“Some of the teachers don’t like to say our long names. So on the first day of school, they say, ‘What’s your white name?’ All of my friends have white names.”

Of course, this doesn’t just happen in British Columbia. It happens in Portland, Oregon, where I live. It happens wherever multiple cultures and languages, one dominant and the others marginalized, bump up against each other. But it’s a problem whether it happens in Bozeman, Montana; Reno, Nevada; or Montclair, New Jersey.

Students’ names are the first thing teachers know about the young people who enter our classrooms; they can signal country of origin, gender, language. Students’ names provide the first moment when a teacher can demonstrate their warmth and humanity, their commitment to seeing and welcoming students’ languages and cultures into the classroom. The poet Alejandro Jimenez wrote about this moment in his poem “Mexican Education”:

When my mother registered me for the 3rd grade

In January of ’96

My ESL teacher

Had trouble with the multiple syllables in my name

She said — “Alejandro is too long, let’s call him Alex.”

My mother looked at the floor and said, “OK.”

To give students nicknames or to refuse to pronounce student names is to reject them from their families, languages, and cultures. To devalue something as intimate and personal as the names their parents bestowed at birth, to whitewash them, to rub out their faces, skins, and vocal cords is akin to saying, “You don’t belong” on the first day of school. So we say their names.

In her fiery poem “Name,” Hiwot Adilow talks back to people who attempt to abbreviate her name or give her a nickname:

i’m tired of people asking me to smooth my name out for them,

they want me to bury it in the english so they can understand.

i will not accommodate the word for mouth,

i will not break my name so your lazy english can sleep its tongue on top,

fix your lips around it.

no, you can’t give me a stupid nickname to replace this gift of five letters

. . . . .

my name is a poem,

my father wrote it over and over again.

it is the lullaby that sends his homesickness to bed

Although I love the study of linguistics, my tongue is a fat slug that tortures every language equally. I took years of French without learning pronunciation; now, in my 60s I struggle through Spanish lessons, still torturing vowels and consonants. So when I take roll on the first day of class, I create a phonemic translation above each student’s name to remind myself how to pronounce it. As Adilow wrote:

take two syllables of your time to pronounce this song of mine,

it means life,

you shouldn’t treat a breath as carelessly as this.

cradle my name between your lips as delicately as it deserves

Every year on the first day of school, I have the opportunity to affirm my students as members of our classroom by cradling their names between lips and trying to sing the songs of their homes.

Resource

Christensen, Linda. 2017. “Name Poem: To Say the Name Is to Begin the Story.” Reading, Writing, and Rising Up: Teaching About Social Justice and the Power of the Written Word (2nd Edition). Rethinking Schools.

***

Name

By Hiwot Adilow

i’m tired of people asking me to smooth my name out for them,

they want me to bury it in the english so they can understand.

i will not accommodate the word for mouth,

i will not break my name so your lazy english can sleep its tongue on top,

fix your lips around it.

no, you can’t give me a stupid nickname to replace this gift of five letters.

try to pronounce it before you write me off as

lil one,

afro,

the ethiopian jawn,

or any other poor excuse of a name you’ve baptized me with in your weakness.

my name is insulted that you won’t speak it.

my name is a jealous god

i kneel my english down every day and offer my begging and broken amharic

to be accepted by this lord from my parents’ country.

this is my religion.

you are tainting it.

every time you call me something else you break it and kick it

you think you’re being clever by turning my name into a cackle?

hewhat? hewhy? he when how he what who?

he did whaaaat?

my name is not a joke.

this is more than wind and the clack of a consonant.

my father handed me this heavy burden of five letters decades before i was born.

with letters, he tried to snatch his ethiopia back from the middle of a red terror.

he tried to overthrow a fascist.

he was thrown into prison,

ran out of his home

my name is a frantic attempt to save a country.

it is a preserved connection,

the only line i have leading me to a place i’ve never been.

it is a boat,

a plane,

a vessel carrying me to earth i’ve never felt.

i speak myself closer and closer to ethiopia by wrapping myself in this name.

this is my country in ink.

my name is the signature at the end of the last letter before the army comes,

it is the only music left in the midst of torture and fear,

it is the air that filled my father’s lungs when he was released from prison,

the inhale that ushers in beginning.

my name is a poem,

my father wrote it over and over again.

it is the lullaby that sends his homesickness to bed

i refuse to break myself into dust for people too weak to carry my name in their mouths.

take two syllables of your time to pronounce this song of mine,

it means life,

you shouldn’t treat a breath as carelessly as this.

cradle my name between your lips as delicately as it deserves

it’s Hiwot,

say it right.

Hiwot Adilow is an Ethiopian American poet from Philadelphia. She was one of the 2018 recipients of the Brunel International African Poetry Prize and author of the chapbook

In the House of My Father (Two Sylvias Press).

***

Mexican Education

By Alejandro Jimenez

My first image of the United States

Came on November 11, 1995

I was waiting in a parking lot

Underneath the lights of a magical place

My uncle said, “Here you find anything”

With his help I pronounced my first real words in English

“gu — al — mart . . . walmar . . . Walmart!”

My aunt walked out of this place

With a green blanket

She wrapped it around my shivering body

I had illegally crossed the border less than two hours before

And now I was warm.

With a big smile on my face —

I thought, I made it.

When my mother registered me for the 3rd grade

In January of ’96

My ESL teacher

Had trouble with the multiple syllables in my name

She said — “Alejandro is too long, let’s call him Alex”

My mother looked at the floor and said, “OK”

It wasn’t until a couple years later

When I knew enough English (and assimilation)

That I realized what had happened

Now, most of my family members do not call me by my birth

name.

That same year I met Mrs. Parrot

She would not allow me to go to the bathroom

Until I pronounced my request correctly

Most of the time I would piss myself.

At that time,

I didn’t know enough English

To cuss her out

So instead I waited until high school

And I would run by her house and spit on her nice lawn

I also used to poop in her fruit tree orchard.

In 4th grade, an ESL assistant would kick my shins under the table

Every time I would mispronounce any of the words

she was holding on a flash card

Until this day I do not find high heels to be attractive.

In 6th grade,

While in the back of the bus with three white kids

Malia Hadley

Whom I had a crush on

Asked me, “Alex, is it true that they call Mexicans beaners?”

(I should have known from her smile that she did not actually want

to broaden her knowledge)

I remembered having beans

The night before

That I did not think about

The implications of her question

“Yes,” I said

Everybody laughed.

. . .

In 7th grade,

My science teacher compared Mexico to trash

He is the reason why I dislike science.

I also used to run by his house and spit on his lawn.

In 8th grade,

My friends and I jumped each other

And started our own “gang.”

We were afraid of what the following school year would hold

After all, that was the furthest any of our parents had gone to

school

I guess punching each other was how we showed support and

guidance

Later, some would drop out

Some would actually join gangs

Some joined the military

And we would not recognize them after their tour

Some would graduate

Very few would go on to college.

In high school,

I was one of four brown faces in AP classes

In a school that was 40 percent Mexican

I always felt weird

When my teachers praised me,

“for not being like the rest of them”

What is this rest of that I am not?

I left my guidance counselor jaw-dropped

When I told her I wanted to go to college.

Instead of guiding me through the application process

She asked me to talk to incoming students and their families

About my success story

Of “how you came from nothing to something.”

My grandmother’s house in Mexico

May not have had running water,

Electricity,

Flushing toilets,

Steak dinners,

Wood floors,

A picket fence,

But

It was

Something.

. . .

I am a green card holder now

I still I have trouble pronouncing some English words

Sometimes my tongue wrestles with itself

It does not know which colonizer’s language it prefers.

I ask my intuition for good judgment in navigating this country

but sometimes it feels like I ask for too much.

I am learning how to thrive in a world

Where I am not wanted if my name is Alejandro

If my skin is too dark

If my accent is too heavy

If my hands are not rough enough.

If my hands are too rough

When my aunt wrapped me in the warmth of the green blanket,

I thought I had made it.

Mexican education in this country:

They will shorten your name to fit their mouths more easily

Sometimes you will think it is easier too

They will be surprised when you want to be successful

Sometimes you will be surprised too

They will tell you that you are better than the rest

Sometimes you will believe them

They will try to turn you against people that look like you

Sometimes they will win

But now I see that a green Walmart blanket

Cannot protect you from everything and everyone

Set up for you to fail.

Read more at www.alejandropoetry.com

Alejandro Jimenez is an immigrant from Colima, Mexico, TEDx speaker, two-time National Poetry Slam semifinalist, Emmy-nominated performance poet and writer whose work centers around cultural identity, immigration narratives, masculinity, memory, and the intersection of them all. He lives in Denver, where he works with youth as a restorative justice coordinator at a public high school, and tries to laugh with his students as much as possible.