Rethinking Islamophobia

A Muslim educator and curriculum developer questions whether religious literacy is an effective antidote to combat bigotries rooted in American history

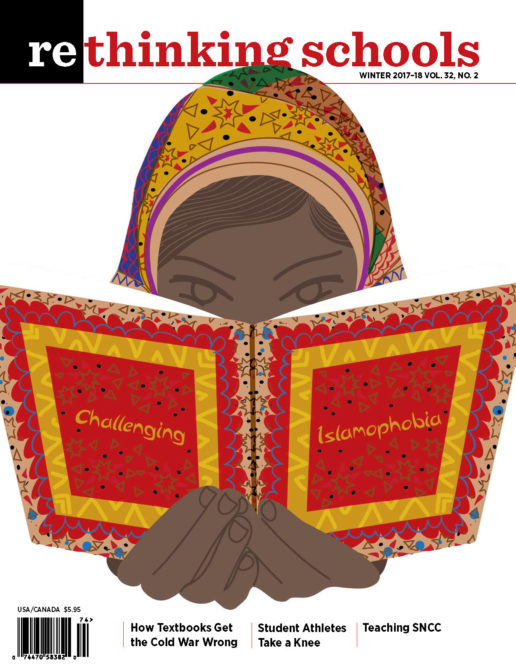

Illustrator: Khalid Albaih (@khalidalbaih and www.facebook.com/KhalidAlbaih)

The increasing violence against Muslims, Sikhs, South Asians, and others targeted as Muslim, suggests we, as Americans, are becoming less tolerant and need educational interventions that move beyond post-9/11 teaching strategies that emphasize our peacefulness or oversimplify our histories, beliefs, and rituals in ways that often lead to further stereotyping. Although I support religious literacy — increasing our knowledge of religious texts, beliefs, and rituals — as a common good and believe increasing religious literacy in schools challenges stereotypes, my experience teaching Islam makes me question whether it is an effective antidote to Islamophobia.

Hate crimes against Muslims increased 67 percent from 2014 to 2015 and were also up a frightening 91 percent in the first half of 2017 compared to the first half of 2016, according to the FBI and the Council on American-Islamic Relations. And in a recent survey conducted by the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding (ISPU), 42 percent of Muslims reported bullying of their school-aged children, and even more disturbingly, 25 percent of those cases involved a teacher.

In reviewing current pedagogies around Islam, I haven’t seen many lessons that address the historical connections between Islamophobia and anti-Black and anti-immigrant racism, yet through my own study of U.S. history those connections are clear and relevant. Instead, the teaching strategies and content I see reproduced most often in textbooks, teacher workshops, online teaching lessons, and even in graduate lectures is what I call the “Five Pillars of Islam” teaching approach, which represents Islam as a religion that can be summed up in a memorizable list of beliefs and rituals. This approach reduces Muslims to a set of stereotypes that reinforce media caricatures of Islam as foreign and unidimensional and Muslims as automatons who blindly follow an inflexible faith. It also does not allow students to make critical connections between Islamophobia and racism.

There is a set script with certain narrative threads that the Five Pillars of Islam teaching approach follows and it comes with a number of profound weaknesses. The story often contains references to violence without providing examples or any real context, making it easy for readers to assume Islam is a foreign religion from a foreign land that is inherently violent. For example, under the heading “The Homeland of Islam,” Ways of the World, a popular high school and college world history textbook published by Bedford/St. Martin’s, explains that “The central region of the Arabian Peninsula had long been inhabited by nomadic Arabs. . . . These peoples lived in fiercely independent clans and tribes, which often engaged in bitter blood feuds with one another.” After describing Muhammad’s 22-year prophecy from 610-632 CE, which is collected in the Quran, the textbook says, “The message of the Quran challenged not only the ancient polytheism of the Arab religion and the social injustices of Mecca but also the entire tribal and clan structure of Arab society, which was so prone to war, feuding, and violence.”

How are students supposed to make sense out of these statements? Free from examples and context, readers can assume that there is something fundamentally violent about the place and people, reinforcing the terrorist stereotype. Nor are these descriptions ever followed by an explanation of the differences between Muslims and Arabs, mimicking the way they are often confused as identical (the majority of Arabs are Muslim; the majority of Muslims are not Arabs).

The Ways of the World textbook then launches into a description of this new religion: The Five Pillars of Islam. A quick Google search for “teaching lessons on Islam” or “teaching lessons on Muslims” illustrates the dominance of the Five Pillar teaching approach. For example, a PBS lesson states that “students explore and understand the basic beliefs of Islam as well as the Five Pillars that guide Muslims in their daily life: belief, worship, fasting, almsgiving, and pilgrimage. They will view segments from Religion & Ethics NewsWeekly and information from Internet sources to look closely at each pillar. Then, as a culminating activity in groups, students will create posters about the Five Pillars for classroom display.”

In this lesson, “Muslims” are represented as all one people and Islam is a fixed set of beliefs dating to 7th-century Arabia. It is instructive to think about what the lesson does not teach. It doesn’t teach us the names of diverse identities that fall under the category of Muslim (Ithna’ashari, Ahmadiyya, Ismaili, or Druze, to name a few). It doesn’t talk about the Muslims who don’t follow all Five Pillars or add a few more to the list. It doesn’t talk about the mind-boggling diversity of rituals and beliefs and texts that have been in continuous flux for 1,500 years across the entire world. Suspiciously, the Five Pillar script sounds a lot like the sanitized Saudi-sponsored version of Islam that is as popular in academic institutions as it is in the halls of government and missionary venues.

These simplistic descriptions have consequences. While describing the legal system that formed in the “Islamic empire” after the death of Muhammad in 632 CE, Ways of the World claims that there was “no distinction between religious law and civil law, so important in the Christian world, existed within the realm of Islam. One law, known as the sharia, regulated every aspect of life.” This is incorrect. There was never a singular Islamic empire but rather multiple centers of power ruled by different leaders. Rulers used a variety of legal codes other than the sharia, like in the Ottoman Empire for example, where they included a secular code known as Kanun. There were no polities that exclusively used sharia in their legal systems. This kind of misinformation reinforces popular beliefs that sharia is an all-or-nothing totalitarian ideology that is intent on overthrowing the U.S. government — and it can lead to absurd, and racist, public policy. According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, 120 anti-Sharia law bills have been introduced in 42 states since 2010 and 15 of those bills have been enacted. One of the chief architects of such legislation, David Yerushalmi, noted the functional purpose of the laws “was heuristic — to get people asking this question, ‘What is Sharia?'”

Even when I search for lessons on Islamophobia, I either get Five Pillar results or the lessons take the conversation out of the United States. For example, in a Teaching Tolerance article called “In a Time of Islamophobia, Teach with Complexity,” the introductory paragraph says, “When teaching about the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), U.S. teachers are often confronted with a dearth of accurate and nuanced material about the history, politics, and people of the region.” The authors suggest lessons about the MENA, which is great if you are teaching about the region. If the goal is to challenge Islamophobia, these lessons won’t be as effective because they communicate that Islam, Muslims, and Islamophobia are from somewhere else rather than from here and that Islamophobia is not also rooted in U.S. history. Rather, I am looking for teaching resources that make Islamophobia personal by connecting it to shared American histories before taking the story global.

Disappointingly, some curricula on Islamophobia includes discussion of violent extremism, a choice that keeps terrorism central to any discussion of Muslims. In an article from Teaching Tolerance called “Expelling Islamophobia,” the authors suggest “integrating Islam” more fully into the curriculum. One teacher explains that “We look at Islam from three different perspectives: history, violent extremism, and Islamophobia. . . . The history of Islam acts as the introduction . . . helping students get a handle on vocabulary and context. The course then pivots to violent extremism — who and where such groups are, their motivations, and how they compare to extremists in other major religions, including Christianity.”

The coupling of Muslims and extremism is troubling because it is a consequence of Islamophobia and fuels further pairing. We must talk about terrorism more, not less, but we need to do it in a way that acknowledges multiple relationships between Islamophobia and terrorism, like U.S. military interventions (it has been 27 years since the first Gulf War), drone warfare, and financial imperialism. And we also need to contextualize any terrorism committed by Muslims with the fact that among the more than 1,600 extremist groups being tracked by the SPLC, the majority are white supremacists and anti-government militias. Regardless, these lessons still don’t give students the opportunity to make connections between Islamophobia and racism nor do they reinforce the fact that Muslims have been part of U.S. history since colonization.

I have seen how common it is to walk away from these Five Pillar recitations thinking that Islam can be summed up in a set of bullet points easily regurgitated on a test. Yet Muslims are complicated people who have rich and varied relationships with their religious identity. The caricatures we see in the media become all that more believable when we are taught that 1,500-year-old traditions can be summed up in neat, formulaic ways. I’m not suggesting these caricatures are used intentionally on the part of educators; quite the opposite, I sympathize with these educators. I taught this way myself in my early years in a community college because the Five Pillar teaching strategy is how I was taught about Islam academically.

Through my teaching experience, I began to ask myself: Will learning about rituals I practice (or don’t) with different levels of dedication over my life span effectively help students make connections between dehumanization and violence? Maybe we should begin our inquiry into Muslims and Islam and Islamophobia in the place where we live rather than in some other place. How does that choice shift our perception about what Islamophobia is and where it comes from? If Islamophobia is a process of dehumanization, who else has been demonized this way in U.S. history? Is there something we could learn from connecting those experiences that will aid our fight against Islamophobia?

After coming to the conclusion that religious literacy does not produce the outcomes I want to achieve in fighting Islamophobia, I decided to write a lesson I could share with other educators who want to teach about Muslims and Islam but don’t want to teach from a religious studies perspective. I work in a variety of educational settings so I wanted the lesson to be effective in middle and high school classrooms and in activist or nonprofit professional development workshops. I wanted to share some of the stories I read in academic texts like Black Crescent: The Experience and Legacy of African Muslims in the Americas by Michael Gomez, African Muslims in Antebellum America by Allan Austin, Servants of Allah: African Muslims Enslaved in the Americas by Sylviane Diouf, Islam in Black America by Edward Curtis IV, A History of Islam in America by Kambiz GhaneaBassiri, Inside the Gender Jihad by Amina Wadud, and others that have enriched my thinking about the stories we use to teach about Muslims, Islam, and Islamophobia. In addition to narrative-changing content, I wanted to use a teaching strategy that reflects an active inclusivity rather than a passive authoritarianism between teacher and students. I wanted everyone to be part of the conversation. I wanted a lesson that would give all of us, Muslims and non-Muslims alike, the opportunity to think differently about our shared history as Americans. I wanted the lesson to blur the lines between who “us” and “them” are, since this is one of the steps of dehumanization we want to interrupt.

Taking all these goals into consideration, I developed a Black Muslim meet-and-greet teaching activity. The lesson empowers participants to fight Islamophobia by raising up voices we rarely hear in the media when we talk about Islam and Muslims — Black Muslims. The personalities included in the lesson are all Black, which not only teaches us about Islam in America but also advances themes in Black history.

Why Black Muslims and not all Muslims? I envisioned this lesson as the first in a series that help students see Islamophobia as a consequence of racism. American racism is an ideology borne out of white supremacy and of the need to steal land, resources, and labor. Islamophobia, like racism, is used to justify American imperialism or the stealing of land, resources, and labor in Muslim-majority countries. I want students to make connections between the abuse of power at home and abroad. There are a lot of heavy topics to cover if we want to empower students to make these connections that must include lessons in both U.S. and global history. I wanted this first lesson to introduce students to a new way of learning about Islam and Muslims that raises awareness of stories most Americans have not heard, setting the stage for deeper inquiry.

I wrote half-page biographies of 25 Black Muslims who lived in the United States from colonization to the present. When identifying the characters who would populate my lesson, I soon discovered that there were too many examples to choose from. In order to remedy this, I defined three time periods — colonization to the Civil War, Reconstruction to 1970s, and 1970s to the present — and then tried to balance out the names according to each time period. The earliest time period contained, predictably, almost exclusively male biographies. For this reason, I overrepresented women in the 1970s-present period, allowing me to also highlight the accomplishments of contemporary women. I chose to tell the story of Betty Shabazz rather than her husband, Malcolm X/Malik el-Shabazz, as I did for Clara and Elijah Muhammad. (Elijah led the Nation of Islam from 1934 to 1975.) These women were fierce activists and educators in their own right but their stories are almost always told in relation to their husbands. I mined a variety of sources — academic texts, documentaries, interviews Ñ for the major events in their lives and then wrote about those experiences in a conversational first-person voice.

I reached out to a friend, Neha Singhal, who teaches social studies at John F. Kennedy High School in Silver Spring, Maryland, which serves the suburban communities within short commuting distance to Washington, D.C. The school is racially, ethnically, and financially diverse, and provided a welcoming setting for piloting the lesson among 25 juniors and seniors.

I introduced myself to the class and asked, “Do you know any Black Muslims?” One of the students, Fatima, said, “I am a Black Muslim. I was born here but my parents emigrated from Senegal.” Nino said there was a Muslim woman in the 2016 Summer Olympics, but no one could give me her name. Derrick offered Elijah Muhammad and told me he started the Nation of Islam. I corrected him that technically, Fard Muhammad started the Nation, but Elijah was the leader for many years. They couldn’t list any other names. I explained to them, “I want to remedy this problem. Black Muslims have been in the United States for 400 years. Why can’t we name more of them?”

I gave each student a half-sheet biography of one Black Muslim and asked them to take two minutes to read the descriptions quietly. I also told them that the names can be difficult for some students to pronounce and they should ask me if they needed help. While they read, I circulated around the room and said the name of the character for each student. I asked them to think quietly about which pieces of information were most important to share with someone who has never heard of their character. This was more challenging than I thought it would be for them. Later, I changed the instructions for the lesson, asking students to flip over their half-sheet biography and create this list in five bullet points. The content in this activity is unfamiliar to most students, so they need an extra minute to absorb the story, summarize the main ideas, and ask for clarification.

I then explained to the class, “In a minute, you will all get out of your chairs and meet and greet one another. How do you do that? You introduce yourself just like you would at a party, but instead of introducing the real you, you will introduce yourself as your Black Muslim character.” Neha and I stood in the front of the room and briefly role-played for them. “Hello, who are you?” Neha answered, “I am Aisha al-Adawiya. I was born in 1944 and grew up in the Black church but I converted to Islam after reading the Quran in the early 1960s. I am the founder and president of Women in Islam, Inc., an organization of Muslim women that focuses on human rights and social justice. I represent Muslim women at the United Nations. I make sure the stories of Muslims are included in Black history through my work at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture at the New York Public Library.” I explained that I would then introduce myself to Neha, and we could follow up with additional questions, particularly those listed on the worksheet.

I gave students the worksheet and explained, “These are questions to help guide your conversations and collect information we can use later in our discussion.” I asked individual students to read them out loud: Find one person who was enslaved. Where were they from? Where did they end up? How did they resist? Find one person who experienced discrimination based on their race or religion. Describe their experience. Find two women. Describe some of their achievements. Find two people who worked for justice. Explain how they do/did that.

Some of the students got up and immediately launched into introductions. “Hi, I am Carolyn Walker-Diallo. . .” “I am Mahommah Gardo Baquaqua. . .” “Were you discriminated against because of your race or religion?” Others needed to be coaxed to get up. Sure, it was one of the last days of school before summer break. But as Neha noted in our post-activity feedback session, some students find it intimidating and uncomfortable when asked to take more responsibility for teaching one another, making it hard to get some of them to take their attention off the teacher. As the lesson progressed, we could see the students becoming more comfortable with the format and it made clear to Neha and me the way that inclusive pedagogies can help students more actively engage in their learning.

The students continued to meet one another for about 25 minutes. After we finished, I asked them to take a seat. I gave them each a handout and said, “At the top of the paper, please list three things you learned about Muslims from this activity.”

After giving them one minute, I asked them to share their answers with the group. Melanie said, “I was shocked to find out that Muslims were enslaved in the U.S. I never heard that before.” Joon quickly added, “I like learning about the successes of Muslim women, so many of them are scholars.” I asked her, “What do you hear about Muslim women in the media?” She looked up in the air inquisitively and said, “I don’t really hear about them.” I said, “OK, what comes to your mind when you think of a Muslim woman?” Another student, Carrie, yelled out, “They are oppressed.” Joon added, “Yeah, I see that, but the women I learned about today, they are a strong group of people.” Other students found it surprising that so many Black Muslims were from West Africa. When I asked why that is important, Nicole said, “We never hear anything about Black people before slavery. They were kidnapped and then end up picking cotton in the South.” Mika said, “I didn’t know Mos Def was Muslim, he changed his name to Yasiin Bey and his music uses Islamic principles.” I asked, “What kind of Islamic principles are reflected in hip-hop?” She had to look at her biography again but then answered, “like being worried about poor people and people who have to deal with discrimination.”

On the same handout, there is a list of questions for students to discuss in small groups. Because we got started a little late, we decided to keep the group whole for the entire discussion, but given the full class period, I would have let the students discuss the questions in small groups before we debriefed together since this will maximize student participation.

I asked the class to give me a few examples of the first Muslims to come to the United States. Fatima offered, “Ayuba Suleiman Diallo was born in West Africa, he was enslaved and ended up in Maryland, on an island off the Chesapeake Bay. He eventually made it back to Africa.” I quickly followed, “Where in Africa? It is a continent, not a country.” She scanned her paper and replied, “Gambia.”

Lydia relayed the story of Margaret Bilali, who we know about because her granddaughter, Katie Brown, was interviewed by the Works Progress Administration (WPA). The WPA, the largest New Deal agency during the Great Depression, employed millions of Americans for public works projects, including the construction of buildings and roads, but they also supported art, music, and theater projects. Fortunately, they chose to collect oral histories of enslaved people and their descendants. It is from these interviews that we get Margaret’s story. “Margaret’s dad was enslaved on Sapelo Island off the coast of Georgia. She remembers seeing her dad and his wife praying on the bead and kneeling on a mat to pray,” Lydia explained. “What does that mean — praying on the bead and kneeling on mat? Why would they do that?” I asked. One of the Muslim students explained that some Muslims use a string of beads to pray, called a tasbih or misbaha, that is similar to a rosary, japa mala, or other prayer beads. Muslims often use a small carpet or mat when praying because they fully prostrate by putting their forehead, knees, and hands on the floor. The prayer mat ensures you are praying on something clean. What’s nice about this lesson is that it makes the connection between Muslims and Black history, and within those biographies, the stories can include religious literacy lessons without religion being the central focus.

We also talked about the ways Muslims fight injustice. Neha offered, “Kenneth Gamble fought injustice. He is the guy in Philadelphia who was a musician and then started a nonprofit to help fix houses in the South Philly community and then sell them to people who are from those neighborhoods. With gentrification taking over entire neighborhoods right now, this is important work.” Sandra offered the story of Clara Muhammad, who started her own schools so they could teach their kids about their religion. “Her husband, Elijah, was put in jail because he wouldn’t fight in WWII,” she added. Marcus said, “Keith Ellison is a Muslim in the U.S. House of Representatives.” I asked, “How does he fight injustice?” Marcus replied, “Being there is important so that when people have questions about Muslims, he can answer them.” Lydia, who played Keith in the activity, added, “He also worked on police brutality issues before he came to Washington.” As we were waiting for the bell to ring, a couple students pulled out their cell phones and started looking up photos of the Muslim characters they learned about. Once they saw Ibtihaj Muhammad’s picture, for example, they made the connection between the face and the story about her shared in the meet-and-greet. After seeing how effective it was at grabbing their attention and making them continue talking about the lesson, I decided to add a PowerPoint presentation with as many open-source pictures of the characters as possible that teachers can use after the discussion.

After working with Neha and her students, I decided to add some questions to emphasize the fact that many of the characters in the activity are still alive. It is important that students be asked to connect the past to the present. In the worksheet, I included the prompt “Find at least one person who has been active during your lifetime. Describe some of their experiences.” In the discussion, I added, “Who would you want to meet or research more? Why?” This last question gives the student a chance to make the story more personal and the character more relatable by thinking about who they admire and why.

In June 2017, a Somali American Muslim woman living outside of Columbus, Ohio, Rahma Warsame, was beaten unconscious and sustained facial fractures and the loss of teeth by a white man who screamed, “You will be shipped back to Africa” before he attacked her. As educators committed to pedagogies of equity and inclusion, we have to help students make connections between race, religion, and the racialization of Muslims.

Our students are bombarded with violent images of Black men and women being killed by the police, immigrants being forcibly removed from their communities, and increasing hate crimes against Muslims. We cannot allow our students to think these are discrete events. The Movement for Black Lives platform reads, “We believe in elevating the experiences and leadership of the most marginalized Black people, including but not limited to those who are women, queer, trans, femmes, gender nonconforming, Muslim, formerly and currently incarcerated, cash poor and working class, disabled, undocumented, and immigrant.” Lessons like the Black Muslim meet-and-greet help students build vocabularies that increase their ability to talk about racism in ways that capture these intersections of oppression. We have to give them new ways of understanding racism if we want them to create solutions in the present and future that humanize all of us.

RESOURCES

For Alison Kysia’s Black Muslim meet-and-greet, go here: http://www.teachingforchange.org/black-muslims

Alison Kysia has been an educator for 20 years. She is the project director of “Islamophobia: a people’s history teaching guide” at Teaching for Change. She wants to offer special thanks to Margari Aziza Hill, co-founder and co-director of the Muslim Anti-Racism Collaborative, for her thoughtful feedback on this lesson.