Sorry Not Sorry

Reckoning with the Power and Limitations of an Apology to Native Hawaiians

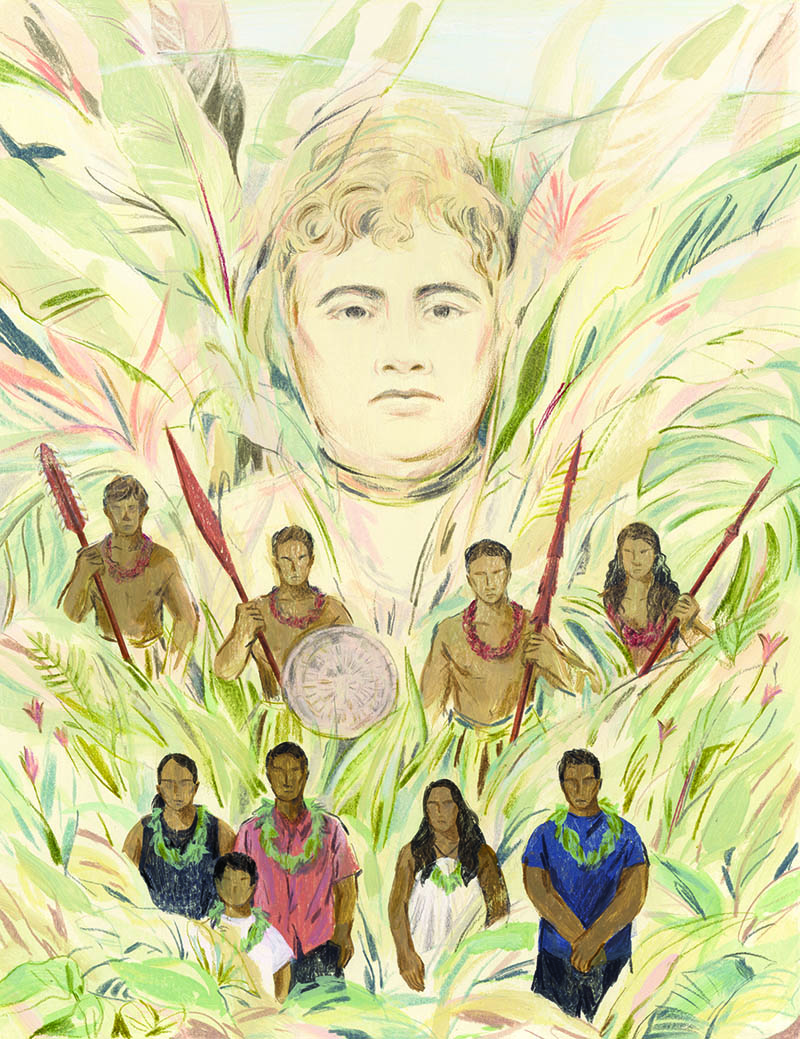

Illustrator: Sally Deng

One evening following the first wave of Hollywood “#MeToo” stories deluging airwaves and newsfeeds in the early winter of 2017, I was having dinner at my dad’s house. My dad’s husband, David, who I have known since I was 18, sat down next to me in the living room while my husband, son, and dad chatted and snacked in the kitchen.

He said, “Ursula, I have been reading the stories of all these women in the paper, and I am just sick. I keep asking myself, ‘How have I been a part of this?'”

I swallowed and thought, “Uh oh. Where is this going?”

He continued, “And I recalled when you were living on 84th Street, and you told us the super was giving you a hard time. I can’t even remember what I said, but I know I didn’t do anything. I just want to say how sorry I am. I should have followed up; I should have made sure you felt safe.”

As David spoke, I felt confusion giving way to memory followed by intense appreciation. Like every woman I know, this “me too” moment surfaced my own personal history of sexual assault and harassment. It is a poignant and dark fact that my list of “me too” moments is so long that until David mentioned that lecherous, dirty-mouthed with-a-key-to-my-apartment super on 84th Street, I hadn’t even recalled that episode. Perhaps I didn’t recall it because although the experience created discomfort in the moment, I didn’t live in that apartment for long, and the harassment never materialized into physical harm.

Now, looking across the couch at David’s face, filled with regret and real anguish, it was easy for me to say, “Wow. I hadn’t even remembered that! But thank you. Thank you so much for saying that.”

A few weeks after the dinner where David apologized, I shared the conversation with my classes.

That day’s lesson started by asking kids to make a list of apologies they had received in their lives. I said, “I want you to list both apologies that landed, ones that helped repair harm, and those that did not land, ones that seemed unsatisfying or incomplete.” I walked to the whiteboard and, as a way of helping them brainstorm their lists, shared my own list, ranging from the silly (when my son “apologizes” for not lifting the toilet seat to pee) to the serious (David’s). Hoping that my list would spark some examples of their own, I said, “OK, you have two silent minutes to jot down as many apology moments as you can think of.”

My U.S. history classes were in the midst of our U.S. imperialism unit. I was about to dive into an investigation of the overthrow of the Hawaiian Queen Lili’uokalani by missionary-born sugar barons in 1893. The lesson culminates in an evaluation of the 1993 Apology Resolution, which:

Apologizes to Native Hawaiians on behalf of the people of the United States for the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii on January 17, 1893, with the participation of agents and citizens of the United States, and the deprivation of the rights of Native Hawaiians to self-determination.

This resolution has always struck me as a surprisingly forthright and uncharacteristically honest, government-endorsed account of the treachery of the United States in Hawai’i. And yet, many people have no idea it exists; it appears to have done little to actually change the place of Hawai’i — and of native Hawaiians in particular — in the larger narrative of U.S. history. Nor has it led to any significant reckoning with what is owed to those whose lives and lands were ravaged and transformed by settler colonialism and occupation.

The disparity between the magnitude of the stated apology and its actual impact on social relations was a rich vein I had tried to mine with students before. Hoping for deeper and more meaningful engagement this year, I was trying something new, asking students to use their own experiences of apologies as an analytical springboard for evaluating what it means for a government to apologize for and reckon with colonialism, land theft, and genocide.

After students created their lists, I returned to my apologies still on the whiteboard and circled the one that said, “David’s ‘me too’ apology.” “I want to say a little bit more about this one,” I said. I described why I thought David’s “I’m sorry” had worked: “It came out of deep self-examination. I thought it was so cool that David’s response to all these revelations about sexual harassment was to think about himself, and how he might have been part of the problem.” I continued: “And it was so long after the fact, so unexpected.”

I shared these musings to model for students where I hoped to take them next. I said, “Now, choose one apology from your list — it can be one that worked or one that didn’t — to explore in more detail.” I asked them to describe the original harm, the apology, and to analyze what made it work or fail. I offered some guiding questions:

- How did the nature of the harm or misdeed shape the kind of apology that was needed?

- What are the characteristics of a genuine apology?

- How do you feel when you get a hollow apology? Why?

- Why are apologies important?

I set the timer for 15 minutes and the class got to work.

Students wrote about divorce, betrayal by friends, sibling cruelty, bullying, forgotten birthdays, and more. Like many of her peers, Justine wrote about the importance of apologies being matched with action:

Post divorce, 2009, my dad sat me down and had a real conversation with me. He apologized for the way he and my mom had been acting. As a child, I just kinda blew through the convo, but in hindsight, it means a lot to know that he felt bad about his actions. . . . Just saying sorry doesn’t cut it, though. I need to see action in order to feel the apology worked. Stop arguing with my mom through me. And he did.

Nora noted the importance of the form an apology takes. She wrote:

My dad didn’t remember and did not care enough to acknowledge me and say, “Happy birthday.” He would leave three days before my birthday, and then, a day after my birthday, send me a text that said, “I am sorry for missing your birthday. I totally forgot. Happy birthday.” If you send me an apology over text I’m not going to accept it because it is not sincere. Now if he had called, wrote a letter and sent it, or even said it to my face, I might have accepted his apology.

Among my students, there seemed to be almost universal agreement that an insincere or incomplete apology can leave the harmed feeling even more wounded than had no apology occurred at all. For example, Jackie wrote about a conditional apology she received from friends who had spread disparaging rumors about her:

I got a text from them saying they were sorry “if” I got hurt “but” they explained all the reasons the stuff they said was “justified.” It was probably the most ingenuine apology I have ever received and left me feeling even more hurt.

Ryan wrote: “When I get a hollow apology I feel angry or I feel like wanting to get the person back.”

Jackie’s final thought gave me chills. She wrote: “Apologies aren’t just important, they are a necessity to having a functional society — without them, everyone would just be mad at everyone else for eternity.”

Later in the week, I handed back the narratives with my comments and said to the whole class, “Thank you for these. They were heartbreaking, funny, moving, and insightful. And we’re not done with them yet. But first, we need to talk about Hawai’i.”

I teach in one of the wealthiest cities in Oregon, so when I asked my classes, “How many of you have been to Hawai’i?” I knew at least half the kids would raise their hands. I quickly and goofily fist-bumped kids in the class whose hands were not raised, as I too have never been to the Hawaiian Islands. Feigning ignorance, I said, “So my understanding is that Hawai’i is really far away. Doesn’t it take a long time to get there?” Kids loudly start blurting how long (six hours) it took them to fly there. Then I said, “Well, even if I won the lottery, I couldn’t hop a plane to Honolulu because my passport is expired.” After a few beats of confusion, kids started hollering, “You don’t need a passport, Ms. Wolfe! It’s part of the U.S.!” “Oh, that’s right,” I joked. “So tell me why is Hawai’i part of the United States?”

This humorous setup (which admittedly wouldn’t fly in many public schools where vacations to Hawai’i are less commonplace) is to focus students on the geographic location of Hawai’i, begging the question: How did this seemingly faraway place come to be part of the United States of America? There is nothing obvious, natural, or inevitable about Hawai’i’s place in U.S. history.

Europeans began arriving on the Hawaiian Islands in the late 1700s, following their “discovery” by Captain James Cook, an English explorer. Though Cook’s first sojourn on the islands was peaceful, that peace didn’t last.

Writer and activist Haunani-Kay Trask argues that within 100 years Hawaiians had been “dispossessed of our religion, our moral order, our form of chiefly government, many of our cultural practices, and our lands and water.” She explains:

When Captain James Cook stumbled upon this interdependent and wise society in 1778, he brought an entirely foreign system into the lives of my ancestors, a system based on a view of the world that could not coexist with that of Hawaiians. He brought capitalism, Western political ideas (such as predatory individualism), and Christianity. Most destructive of all, he brought diseases that ravaged my people until we were but a remnant of what we had been on contact with his pestilential crew.

The next assault on Hawaiian sovereignty came with a wave of U.S.-born missionaries, followed by the rise of the labor- and resource-intensive sugar economy, which was dominated by a white planter elite. This elite placed intense pressure on the Hawaiian monarchy to sell land, negotiate favorable trade agreements with the United States, and ultimately cede power to businessmen.

Support for these policies was growing back in the United States, where imperialists increasingly projected the ideology of Manifest Destiny abroad, with newspapers like The New York Times stating that the United States was “bound within a short time to become the great commercial, and controlling, and civilizing power of the Pacific.”

In 1887, U.S. marines helped install King Kalākaua and a new constitution (the aptly named Bayonet Constitution), stripping the monarchy of much of its power. It also disenfranchised most native Hawaiians through property requirements, ensuring political power would rest firmly in the hands of the sugar barons. When Queen Lili’uokalani ascended to the throne in 1891 she wanted to take back the power ceded under the Bayonet Constitution and lower property requirements for voting.

It was this reassertion of Hawaiian sovereignty that led the so-called “Committee of Safety,” made up of mostly European and U.S. planters, to hatch its plan for the Queen’s removal and an end to the Hawaiian monarchy. The coup was bolstered by the support of the U.S. ambassador and 250 Marines; a treaty of annexation was quickly introduced to Congress.

Yet, U.S. annexation of Hawai’i was still not a foregone conclusion. The new president, Grover Cleveland, opposed annexation. In his 1893 statement to Congress, which I read with students, we find an incredible presidential admission:

By an act of war, committed with the participation of a diplomatic representative of the United States and without authority of Congress, the Government of a feeble but friendly and confiding people has been overthrown. A substantial wrong has thus been done which a due regard for our national character as well as the rights of the injured people requires we should endeavor to repair.

Here Cleveland admits an unlawful act of war by representatives of the United States and suggests some form of reparations. Since it is so rare, this honest reckoning with U.S. imperialism is worth acknowledging. But it is important to surface with kids the racism infusing both sides of the annexation debate.

On the pro-annexation side, students read the famously sickening speech by Albert Beveridge, which claims God “has made us adept in government that we may administer government among savage and senile peoples.” On the anti-annexation side, students analyze anti-imperialist political cartoons that depict the queen as a pickaninny, the wildly disparaging caricature of African Americans ubiquitous in U.S. popular culture at the time.

I want students to understand Cleveland’s opposition to annexation in this racial context, not motivated only by the wrongdoing of U.S. representatives, but also by a belief that the Hawaiian people could not become fully American, that they were “unassimilable” on racial grounds.

After looking at Cleveland’s speech, I remind students of their apology analysis. I say, “Before we talk any more about Queen Lili’uokalani and President Cleveland, pull out your apology narratives.”

Students go to their binders and within a minute have their narratives in hand. I say, “Take a minute to re-read your piece. Remind yourself what you decided were the attributes of a genuine apology. Highlight them.” We generate a list.

Miles calls out: “You feel true regret.”

Bela says, “Prove that you understand what you did was wrong.”

Cami’s contribution results in a whole chorus of yups: “Real apologies are not offered just to make you feel better; they’re offered to make the person you hurt feel better.”

Alejandro adds: “They have to go along with real change in behavior. You can’t just say you’re sorry. You have to be sorry.”

“So,” I say, “did Cleveland’s words meet our criteria for a genuine apology? Go ahead and talk about that with your tablemates.” As I walk around, I overhear snippets of their analysis.

Cameron says, “How can it be an apology if the word ‘apology’ isn’t even in it?”

Morgan notices, “It kind of reminds me of what Cami said because his words seem more about saving face than really apologizing — that whole ‘due regard for our national character’ bit.”

But Andrew sees it differently: “I don’t know. Cleveland is saying what the Americans did was wrong and he is offering to put the queen back in power. That seems like a pretty authentic apology to me.”

Forest says, “But Andrew, the queen had to agree not to punish those guys like Sanford Dole who had carried out the overthrow. If Cleveland is saying what those guys did was wrong, why should they get off scot-free?”

Ultimately, of course, the insurrectionists do get off scot-free. And Congress, under the cloak of its imperial war with Spain, annexes Hawai’i with the Newlands Resolution in 1898. But just because an act is passed by Congress doesn’t make it legal.

Queen Lili’uokalani was well aware of the law. Here is an excerpt from her letter of protest to President William McKinley:

I declare such a treaty to be an act of wrong toward the native and part-native people of Hawaii, an invasion of the rights of the ruling chiefs, in violation of international rights both toward my people and toward friendly nations with whom they have made treaties, the perpetuation of the fraud whereby the constitutional government was overthrown, and, finally, an act of gross injustice to me.

This document is important to introduce to students not only because it raises the legal dubiousness of the U.S. annexation, but also because it gives voice to an important history of resistance to U.S. occupation, a resistance that was widespread and has been almost completely written out of the history books.

In her book Aloha Betrayed, Noenoe K. Silva shows how native Hawaiians wrote stories, songs, poetry, editorials, and essays powerfully opposing and decrying annexation and the racist assumptions underlying it. But because these tracts were printed in Hawaiian, not English, they have been largely ignored by mainstream histories that quote mainly from the English language newspapers of the time.

It’s time for students to tackle the central question of the lesson: How might the United States and its current inhabitants act to repair some of the “fraud” and “gross injustice” noted by Lili’uokalani?

One more time, I ask students to return to our list of attributes of genuine apologies to consider as they read and highlight the 1993 Apology Resolution. After a bit, I ask for volunteers to share what they have marked. Students immediately notice that the apology does not come until the very end of the document. I say, “So why is that? What’s happening in the rest of the resolution?”

Somewhat indelicately, Nick offers: “It’s really just telling the story of Hawai’i — who lived there first, what happened when the Europeans arrived, how the queen was screwed by the American businessmen.”

“Yes!” I affirm. “So why give us that history lesson? What’s that have to do with an apology?”

Morgan chimes in, “It’s like what I said before, you have to show that you understand the wrong before you apologize for it. The history is showing that the government understands what it did wrong.”

“Great,” I say. “So what about the apology itself? What do you make of that?”

Michael said, “Well, I highlighted the part where Congress ‘expresses its commitment to acknowledge the ramifications of the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawai’i, in order to provide a proper foundation for reconciliation between the United States and the native Hawaiian people.’ I thought that was kind of weird.”

“Huh. Why weird, Michael?”

“I don’t know. I guess it makes it sound like native Hawaiians and Americans are fighting, which doesn’t seem true to me.”

“You know,” I say, “that is such an interesting point. What do we know about what native Hawaiians think about this apology? And if we don’t know what they want, how can we think about something like reconciliation?”

I pause to show a short cable news clip from the evening in 1993 when the Apology Resolution was passed. The clip offers some statistics on the outrageously high rates of poverty, ill-health, and incarceration among native Hawaiians, as well as some different options for the future, ranging from seeking federal recognition of native Hawaiians (as is done with some Native American nations) to full independence.

Students are most impressed by Haunani-Kay Trask, an activist in the sovereignty movement; she and her supporters call for the return of all publicly held lands to Native Hawaiians. She is a fiery and persuasive speaker, exclaiming, “We are not American! We are not American! We will die as Hawaiians! We will never be Americans!” When I stop the film, someone asks, “So did that ever happen? Did they get any land returned to them?”

“Not yet,” I say.

Following this too-brief engagement with modern Hawaiian activists, I ask students to respond in writing to a series of questions, the answers to which they will share in a discussion, the culminating activity:

- What do you think of Congress’ 1993 apology?

- Is it appropriate for one generation to apologize for another generation’s wrongdoings?

- Is an apology the first step on a path toward reparations?

- If so, do you support or oppose reparations in this case?

Here is part of what Jackie wrote:

I think the apology is a good idea. However if you are going to issue an apology there has to be reparations with it. The U.S. literally took away their land and leadership and forced its way onto their land to claim it as their own. If that isn’t cause for reparations, then I don’t know what is.

A number of students were uncomfortable with the idea of one generation apologizing for the misdeeds of another, but Otis wrote:

It is appropriate for one generation to apologize for a past generation’s misdeeds if the repercussions are still affecting the wronged people. That’s definitely what’s happening in Hawai’i.

Here’s Justine, whose mother is Hawaiian:

I think it was important for the president to recognize the wrongdoings of America. BUT. What makes for a good apology is ACTION. I want to see Hawai’i become a sovereign nation. I’ve seen where my family lives. I hate seeing luxurious rich Americans ride around in their golf carts sporting “Hawaiian shirts.” I think it is a bit of a slap in the face to say, “I’m sorry,” but then not give anything in return or show that they care about Hawaiians and their well-being. This apology should have been the first step toward SOVEREIGNTY.

The lesson I share here seeks to build on what students already know about the nature of apologies — what heals, what wounds, the importance of honesty and action — to grasp the inadequacy of the U.S. government’s Hawai’i apology decoupled from reparative action.

I am not suggesting any kind of equivalency between personal apologies and calls for state action to address the legacies of genocide, slavery, and colonization. But activating students’ own experiences can be one way to begin wrestling with what a real reckoning with the original sins of the United States might look like. Given the stark inequities in the United States, and their clear and irrefutable connection to the theft of people’s land, labor, and liberty in the past, I want to guide my students toward seeing reparations as plausible, rather than as the outlandish plot of shiny-eyed radicals.

The Apology Act and the question of reparations is only one strand of the battle for justice in Hawai’i. I recognize the need for additional attention in my curriculum to contemporary Hawaiian movements, which are complex, diverse, and dynamic. As Noelani Goodyear-Ka’ōpua makes clear in the introduction to a wonderful collection of essays, A Nation Rising:

These Hawaiian movements for life, land, and sovereignty changed the face of contemporary Hawai’i. Through battles waged in courtrooms, on the streets, at the capitol building, in front of landowners’ and developers’ homes and offices, on bombed out sacred lands, in classrooms and from tents on the beaches, Kanaka Maoli [native Hawaiians] pushed against the ongoing forces of U.S. occupation and settler colonialism that still work to eliminate or assimilate us.

I intend this lesson to be a tiny act of solidarity with these movements for “life, land, and sovereignty,” asking students to reckon with the past and consider what a true act of apology might look like.

Ursula Wolfe-Rocca teaches at Lake Oswego High School in Oregon. She writes frequently for Rethinking Schools.