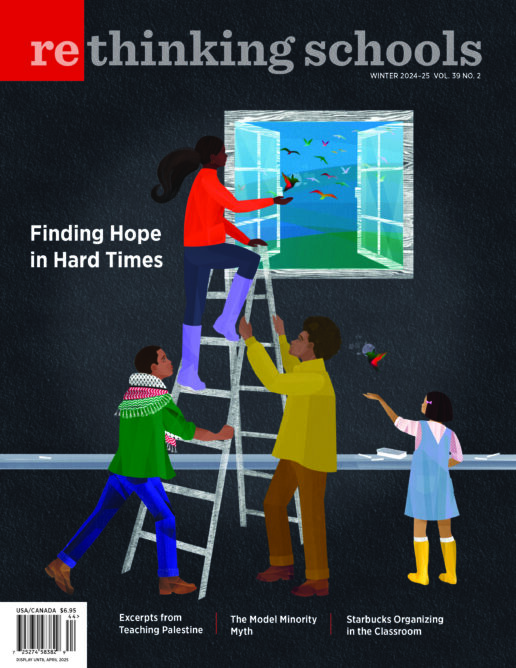

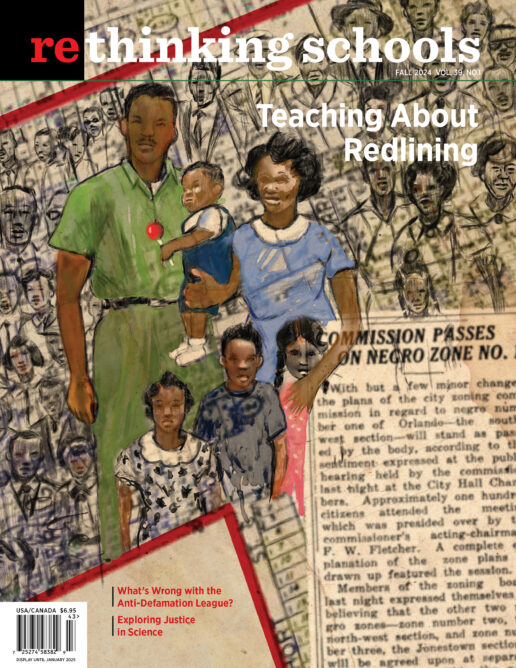

Volume 39, No. 4

Volume 39, No. 3

Volume 39, No. 2

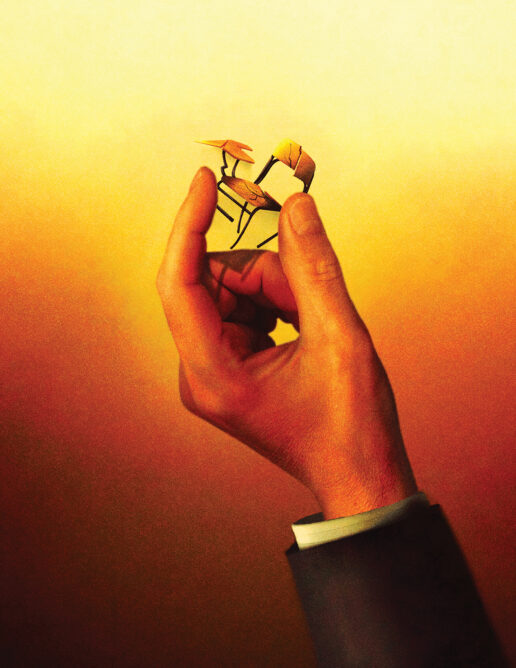

Volume 39, No. 1

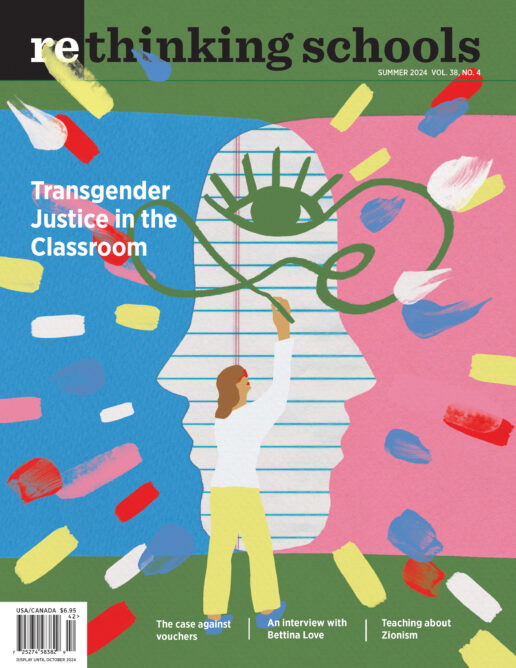

Volume 38, No. 4

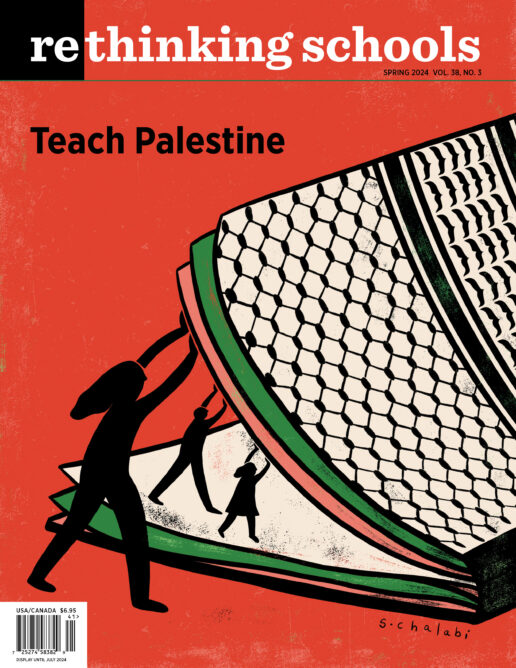

Volume 38, No. 3

Spring 2024

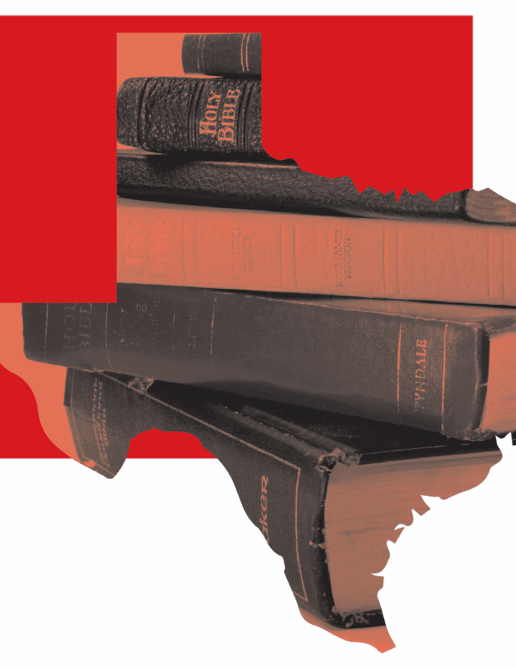

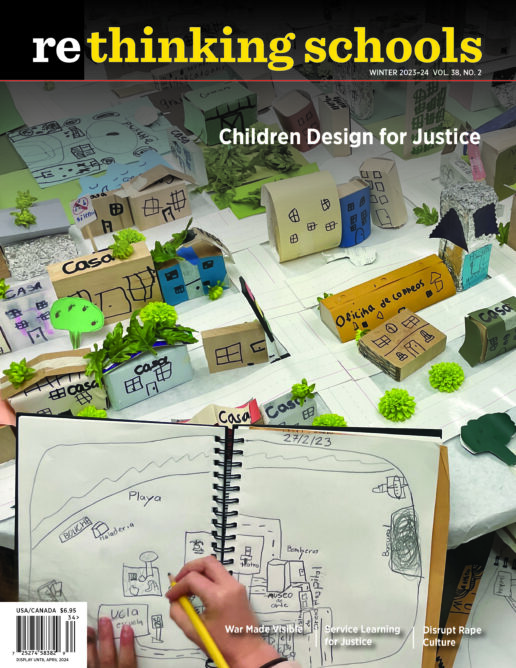

Volume 38, No. 2

Winter 2023-24

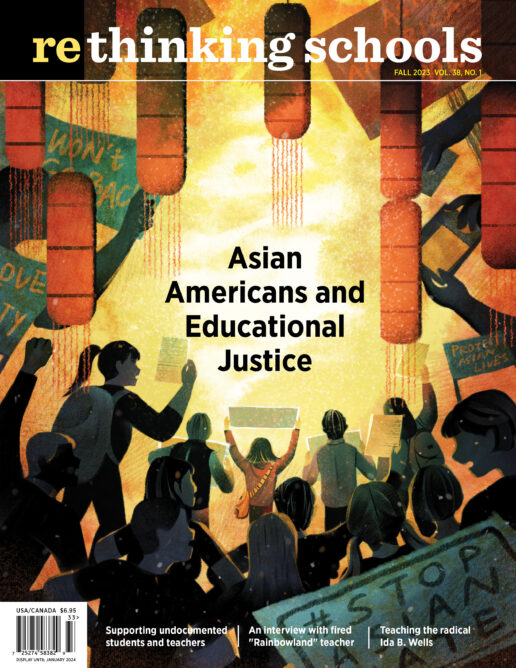

Volume 38, No. 1

Fall 2023

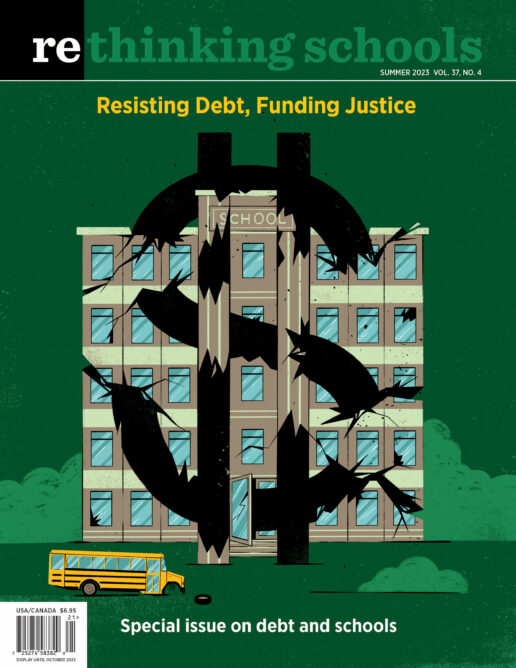

Volume 37, No. 4

Summer 2023

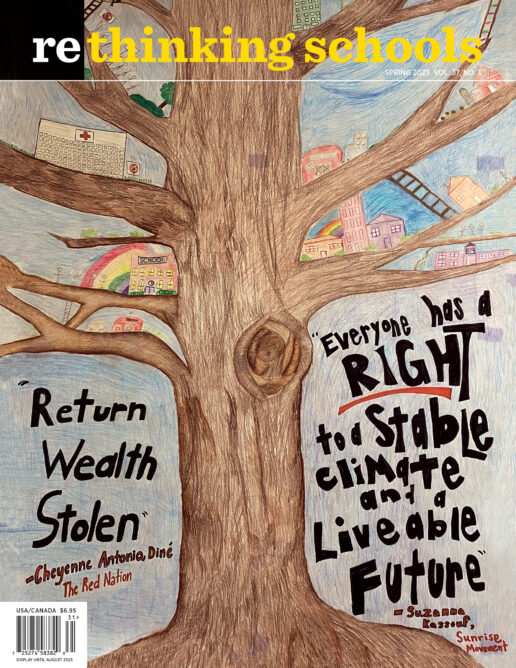

Volume 37, No. 3

Spring 2023

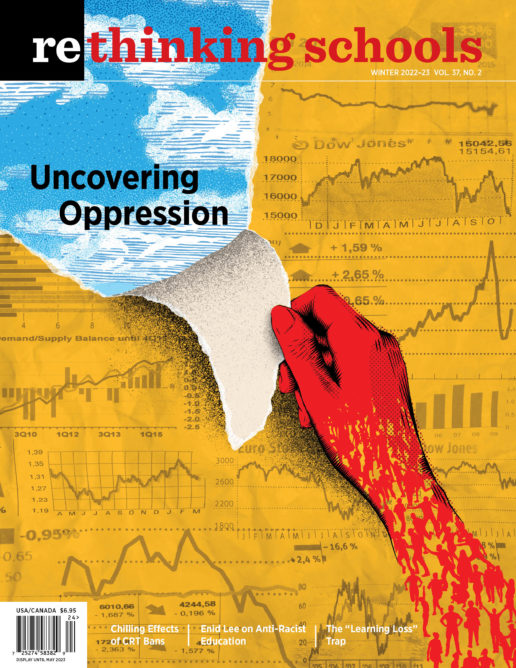

Volume 37, No. 2

Winter 2022-23

Volume 37, No. 1

Fall 2022

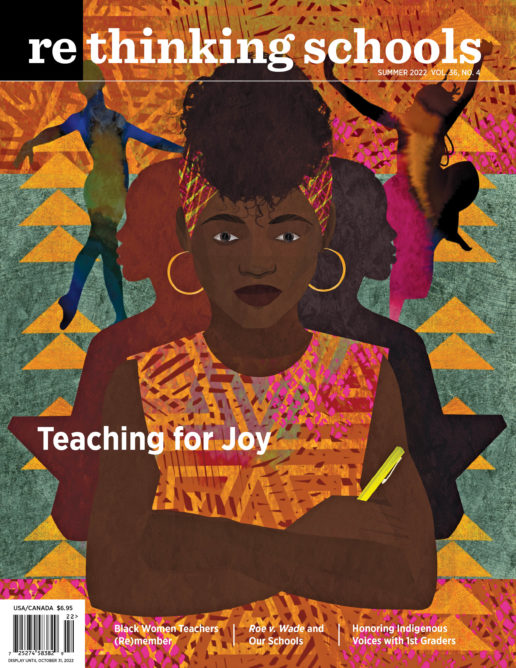

Volume 36, No. 4

Summer 2022

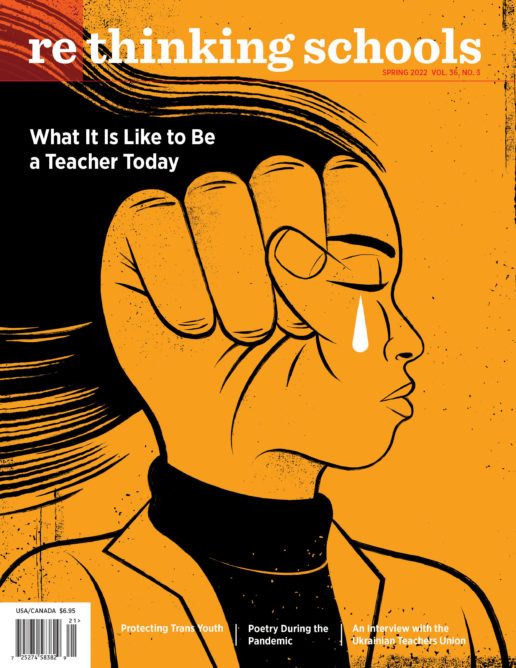

Volume 36, No. 3

Spring 2022

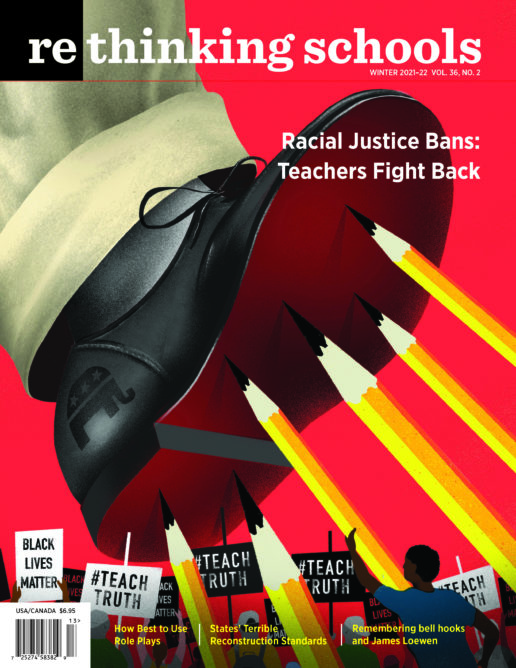

Volume 36, No. 2

Winter 2021-22

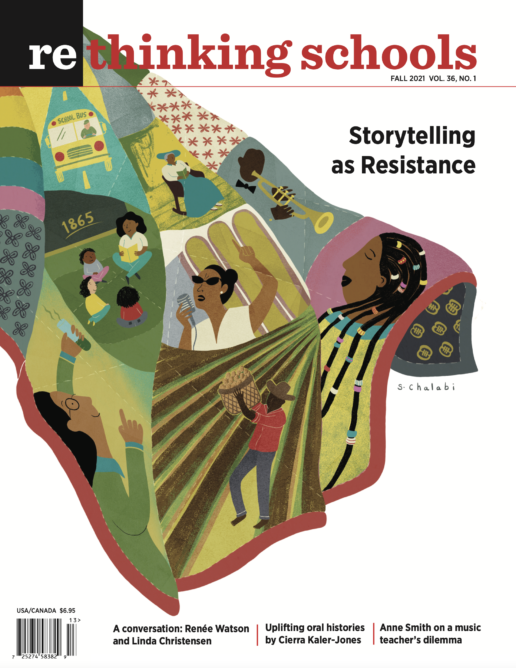

Volume 36, No. 1

Fall 2021

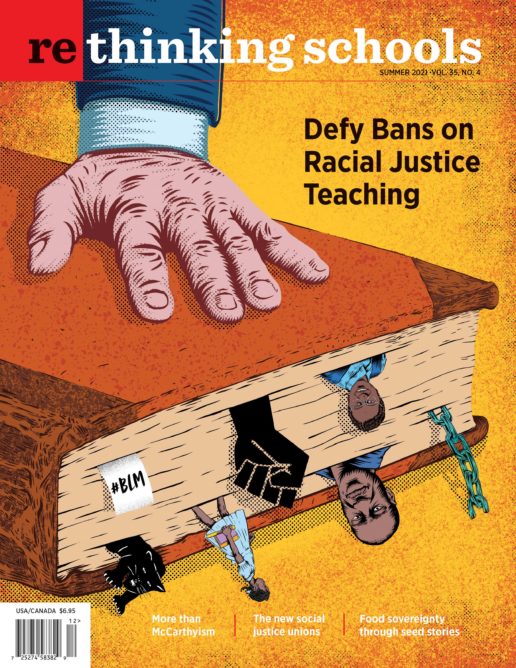

Volume 35, No. 4

Summer 2021

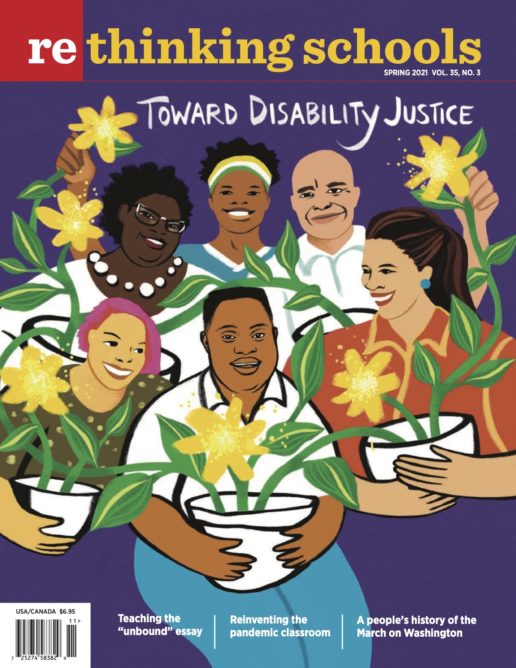

Volume 35, No. 3

SPRING 2021

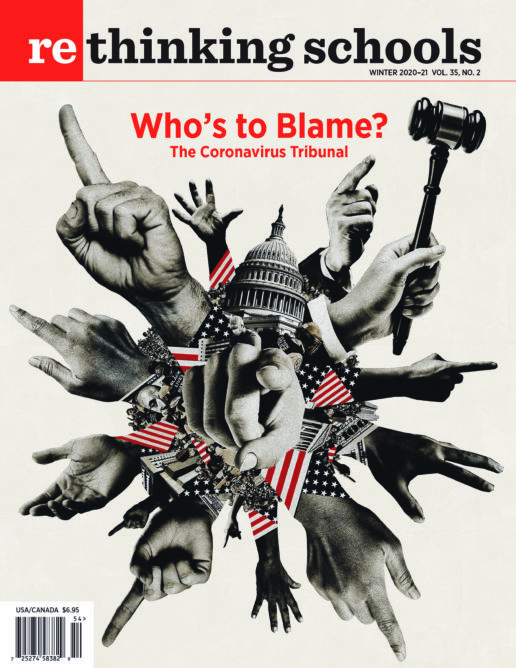

Volume 35, No. 2

WINTER 2020–21

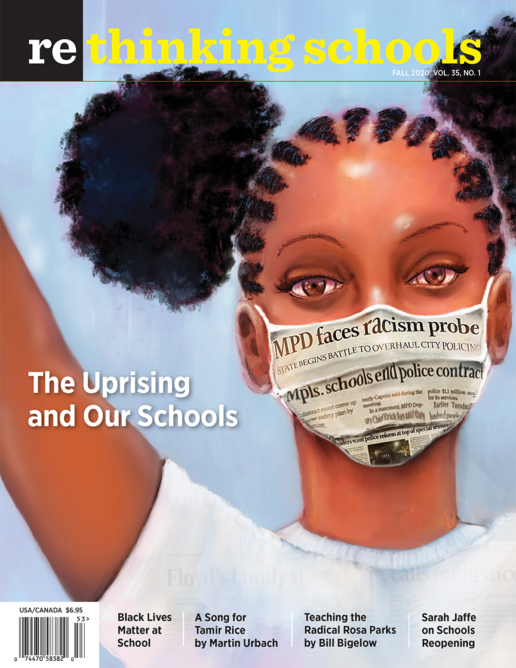

Volume 35, No. 1

FALL 2020

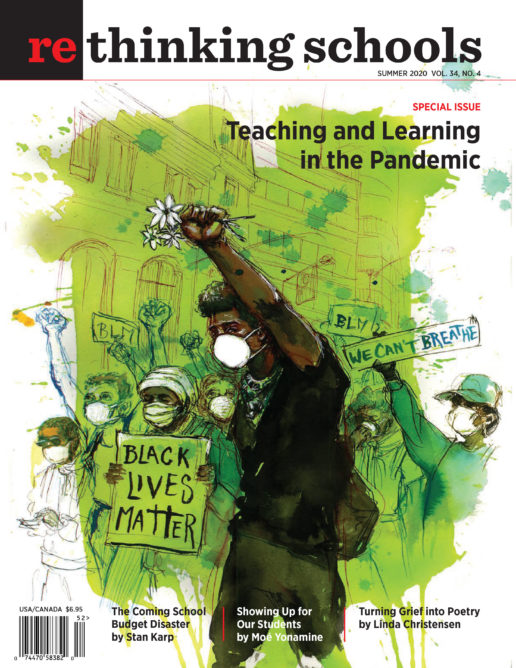

Volume 34, No. 4

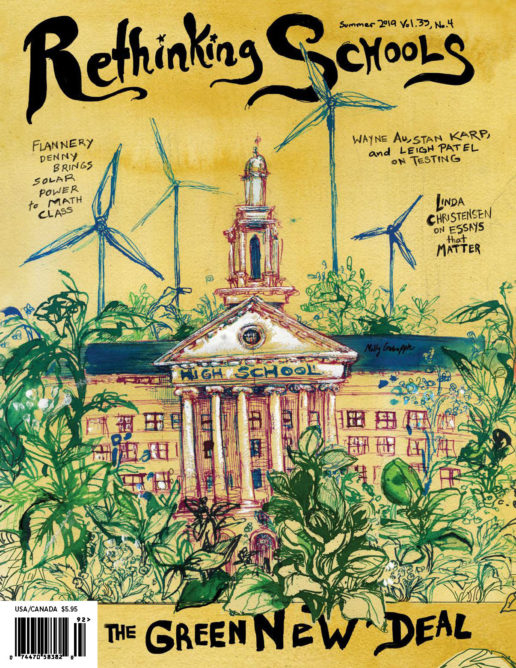

SUMMER 2020

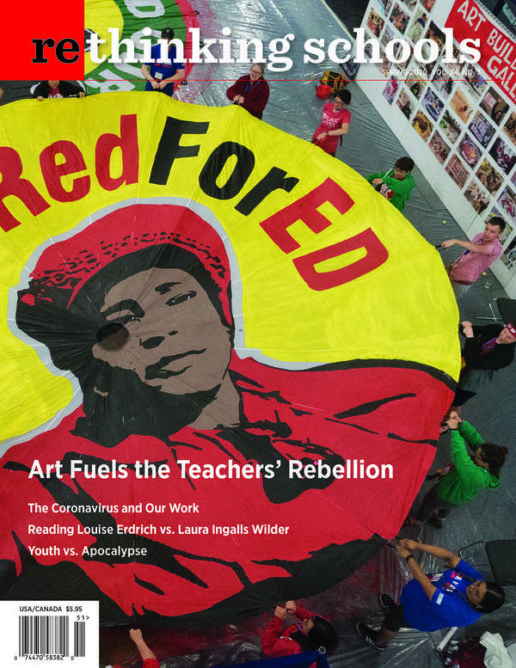

Volume 34, No. 3

SPRING 2020

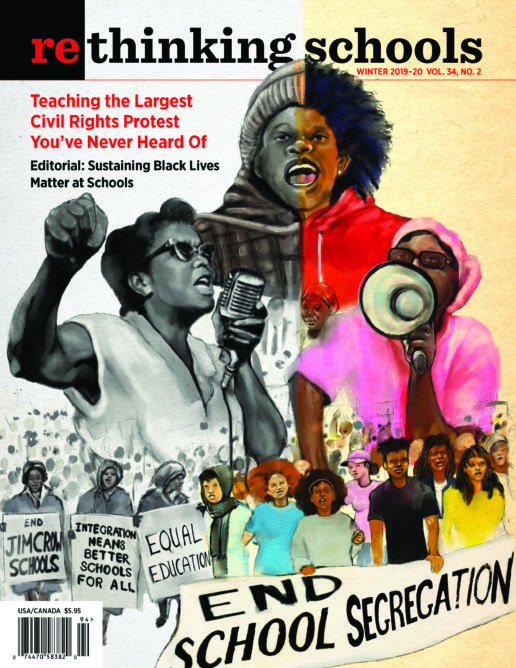

Volume 34, No. 2

Winter 2019-20

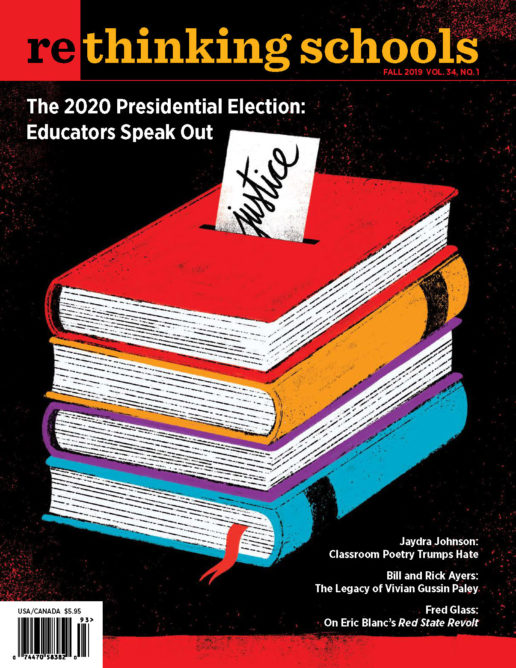

Volume 34, No. 1

Fall 2019