Saving Banks and Failing Schools

The Twisted Logic of the U.S. Debt Economy

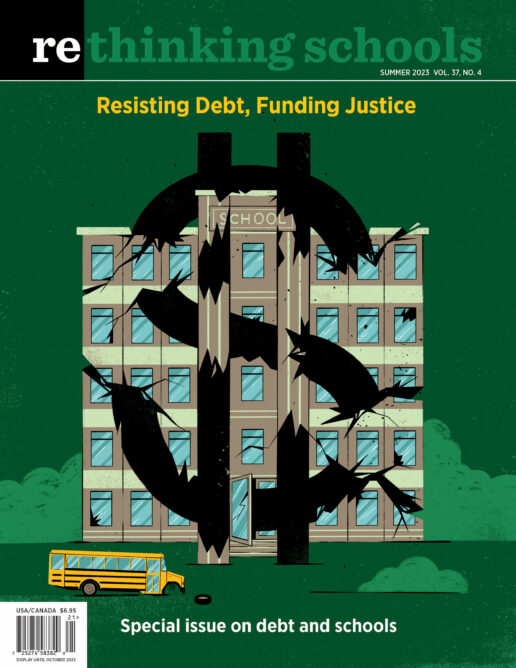

Illustrator: Adrià Fruitós

Last March, the federal government rushed to guarantee $20 billion for uninsured wealthy depositors after the second largest bank collapse in U.S. history. Around the same time, a Rethinking Schools editor was forced to vacate his Philadelphia classroom because of a massive radiator leak. The leak, which he and other teachers who shared his classroom had been complaining about all year, had gotten so bad that it was dripping onto students’ desks in the floor below, finally prompting repair. These two stories — one covered extensively in national and international headlines, the other so common in Philadelphia schools it was barely noted by other teachers in the building — at first glance seem unrelated. But together, they reveal a society that prioritizes the profits of the obscenely wealthy over the needs of our children.

The speed with which the federal government has repeatedly rushed in to hand over billions of dollars to failing bankers and venture capitalists stands in stark contrast to the meager funds allocated to our children’s education. As Stan Karp points out in his primer on school funding in this special issue, the United States remains one of a few wealthy countries that does not include the right to an education in its national constitution; the federal government provides only about 8 percent of education spending.

This leaves a “patchwork U.S. system of local property taxes and 50 separate state funding systems” to bridge the gap. The reliance on local property taxes as a primary source of school funding — in a country where the top 1 percent owns 33 percent of the wealth and the bottom half owns only 2 percent — produces a stunningly unequal distribution of school funds. Add to this that the majority of states have flat or regressive funding formulas (which give schools in poorer districts equal or less funding than schools in wealthy districts) and the lie that the United States is the land of equal opportunity collapses faster than Silicon Valley Bank.

This has created a school system where teachers and students in wealthy school districts enjoy lavish facilities like Carmel High School in suburban Indiana, which lit up TikTok this spring with videos of its multiple gyms, café and bookstore, recording studio and planetarium while others, in districts like Philadelphia, are literally poisoned by the toxins in their aging buildings. Surrounding the house of cards funding system propping up our schools is a growing monster of school debt. When cash-starved school districts search for funds to update their heating systems or air-condition classrooms, they find governments claiming they’re broke and banks flush with cash, happy to profit off lending it out.

Deep-pocketed banks are as much a result of government policy as destitute school districts. In particular, the government responded to the 2008 financial crisis by flooding financial markets with trillions of dollars in new money while purchasing trillions of dollars of debt from the biggest banks. As economist Nomi Prins writes in her book Permanent Distortion: How the Financial Markets Abandoned the Real Economy Forever, this has created “a seismic rift between, on the one hand, economic growth, wages, and a decent standard of living and, on the other, market-driven wealth accumulation that during a devastating global pandemic minted nearly 500 new billionaires in 2020 alone.”

Where the banking and education sectors meet is in the widening pool of debt. As Eleni Schirmer writes in this issue, debt is “the great unequalizer” — it punishes those who have the least.

This is true for the 43 million people in this country who have taken on student loan debt — paying more for their education than their wealthier peers who can avoid taking out loans that add interest and fees to the rising cost of education. It is true for educators — as Jason Wozniak writes about in this issue — half of whom take on an average of $58,700 in debt to graduate into a job that pays less than comparable professions. And it is true for school districts. As Schirmer explains:

When school funding formulas fail to provide sufficient resources for schools, the district (or municipality) has to go to the bond market to issue a bond. A bond is basically a big, complicated, legally binding IOU. Financial investors buy the bond, and give the school district the cash they need. In exchange, the school district pledges to pay the financial investors back over the next several decades — plus interest and fees, which are set according to the district’s credit rating.

But because a district’s credit score is typically based on that district’s property values and residential incomes, “the more working class the neighborhood, the worse their credit rating. This means poorer schools face higher interest rates; greater portions of their resources get shuttled into fees and payments to Wall Street banks.”

Debt, in all its many forms, both feeds on inequality and amplifies it. Much of the inequality in property wealth that produces unequal school funding began with the racist practice of redlining, when banks systematically denied credit and investment to communities of color. Black student borrowers typically owe 50 percent more upon graduation than their white peers, a disparity that grows as interest piles up and earnings lag. Black and Brown families, and especially women, have significantly more overall debt and more of the particularly onerous forms of medical debt, government fees and penalties, and predatory loans that trigger the involvement of courts and aggressive collection practices. Debt relief is but one form of overdue reparations for decades of injustice.

No one should have to mortgage their future by going into debt.

We desperately need curricula that question the logic of debt, interrogate the growing power of financial institutions, and invite students to critique a political economy that produces such vast inequality. In this issue, Philadelphia teacher Freda Anderson offers suggestions for where to start, detailing attempts to engage students on the question of school debt and to help them imagine a different world. Unfortunately, much of the available economic curriculum focuses on “personal finance” and legitimates and reinforces current economic relationships. High school teacher Hyung Nam offers a scathing critique of the growth in “financial literacy” curriculum that sells students a bill of goods about how our economy works and feeds them corporate propaganda.

A society that continues to allow wealthy bankers to profit off of children, and to leech public funds from the most vulnerable, is broken. But we can respond. From fights against school lunch debt to organizing campaigns for fair funding, local struggles contain valuable lessons for how we can push for a more just economy.

We should begin by flipping the language of debt. Whether it’s for the interest and fees they charge our school districts, the taxpayer-funded bailouts, or the trillions they have poured into the fossil fuel industry destroying our planet, it’s Wall Street that owes us. We must stop them from profiting off our impoverishment. No one should have to mortgage their future by going into debt to pay for college or a necessary medical procedure. School districts shouldn’t go into debt to update toxic buildings. Education and health care are rights that should be guaranteed to all. For too long these rights have been rationed, restricted, and denied to serve the interests of the wealthy. It’s time they pay their debt.