Teachers Living and Resisting Indebted Life

I remember the first time I witnessed the ghost of debt haunting a teacher. It was a cold late winter night in Chicago around the time I was 13. I woke to get a glass of water sometime after midnight. Passing through the dimly lit hallway, I happened upon my father hunched over a notebook and pencil at his work desk. Under faint nightlight, he was scribbling and erasing all over the page. I could hear how hard he was pressing down on the paper each time he left a mark. Even at that late hour and under a sleepy daze I could tell he was stressed.

My father was a teacher and school administrator for more than 30 years on the South Side of Chicago. On weekdays we had a tradition of talking at the kitchen table before we went off to school, he to work, me to study. The next morning, I asked him why he was working so late at night. “The debts don’t rest, son,” he offered meekly, “and so I got to always figure out a way to pay them.” He sat up from the table, poured his remaining coffee down the drain, and went into his room to get dressed for the day’s teaching ahead. I sat there, not fully aware what he meant and how heavy debt could weigh on someone.

Years later, I accumulated my own debt to contend with. Unlike my father, however, my debts came from student loans. Neither my father nor a lot of teachers of his generation could ever imagine their kids going more than $200,000 in debt simply to become a public high school teacher and later a professor. My father is gone, took some though not all of his debt with him, but I’m still here trying to figure out how the heck the richest country in the history of the world could bury its educators under mountains of debt.

Americans owe about $1.7 trillion in student debt. A large portion of this debt is held by teachers.

According to a 2017 National Public Radio survey of 2,000 public school teachers, the vast majority of indebted teachers are “terrified” about their student loans. They have good reason to be. Per the National Education Association (NEA), the 2018–2019 average public teacher salary in the United States was only $61,730. This is nowhere near enough to cover costs of living, and also to pay off the mounds of debt that teachers carry.

Nearly half of all educators took out student loans to pay for college, owing $58,700, on average. Among them, one in seven still owes more than $105,000, according to NEA research. Student, but also other types of household debt, are major issues for most teachers, but especially for women, who hold a staggering 66 percent of all student debt and especially for Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) educators who typically have more debt when they graduate from college than their white peers. In fact, the Center for American Progress argues that student debt is an overlooked barrier to increasing the number of Black and Latinx classroom teachers.

Teachers regularly face debt realities and ghosts on their own. One of the most difficult aspects of living the indebted life is the shame and isolation that accompany it. Debtors often feel indignity, guilt, and/or failure for being in debt. This frequently leads debtors to self-isolate, and to avoid talking about their debts in public. The more we internalize these feelings, the more depoliticized debt becomes.

As a scholar-activist, I have talked with teachers about the debts they owe. Most of the teachers I’ve spoken to over the past three years wouldn’t consider themselves debt cancellation activists. Others I met are actively engaged in debt abolition struggles, working to cancel not only student debt, but also other types of debt like medical, debts incurred from court fees and time spent in prison, and debts owed by countries in the Global South to Global North banks. For many, this was their first time speaking with someone about their debt stories. The conversations seemed to offer debtors a chance to come out of debt’s shadows and speak honestly about their struggles. The silence and shame around debt are often as painful as the financial burden.

What I heard should concern anyone who cares about educators and education. One can’t help being moved by stories like those of Richelle, a 34-year-old Black mother, former teacher, and now principal of a school in Los Angeles, carrying more than $250,000 in student debt. As a Black woman with little access to generational wealth, Richelle took on massive amounts of debt to pursue her postgraduate degrees that would give her the certifications needed to do what she calls the “care work of teaching.” For Richelle, loans were a “means of survival” to make ends meet while advancing her teaching career. Like others, she was forced to make a deal with the debt devil: take loans and service them the rest of your life or continue to struggle without a degree or certification in a society that often stratifies populations without advanced degrees, and that has eliminated most public safety nets. “You have to borrow the money in the first place, ’cause you don’t have it,” she told me, “but then you’re stuck paying over $300 a month or more forever, and who can do that?”

Other teachers tell similar stories about how debt “swallows up life,” as Nitzelis, a grammar school teacher in Puerto Rico, put it. Years of colonial rule and disaster capitalism has burdened Puerto Rico with an unpayable debt. Working two, sometimes three jobs at a time to make ends meet and satisfy creditors, Nitzelis daily feels the weight of her country’s debt as well as her own. Banks and the U.S. government have made debt a device to extract untold wealth from Puerto Rico and its people. As a result, teachers like Nitzelis have been colonized by debt. “[Debt] really engulfs us,” she told me. “It’s like it’s a mechanism. It’s something automatic. It’s like a practice. It’s almost like it was a birthmark. Like a social birthmark. Like being in this island that’s how it is. I’ve been born into crisis after crisis. Because that’s how we live here.” Being in a constant state of debt crisis wears on Nitzelis: “Emotionally, I feel like I’m burnt out most of the time, especially when the semester starts.” Who could blame her?

Debt has a peculiar and punitive relation with time. It follows people from the past into the present and forecloses on the future. If education is meant to open opportunities for bright futures, debt often stifles them. Nitzelis, like many teachers, comes from a precarious economic past, struggles to live with debt in the present, and doesn’t have much hope for a brighter future if debt is always there waiting for her. She, like Richelle, told me that early on in her studies student loans and other types of debt were the only means of survival. “There was no other way to live. That’s just it for me, I don’t come from generational wealth. My family comes from el campo [the countryside]. There is no other option. Like there is nothing else.” For her, and many teachers elsewhere, “There was no plan B, there is no ‘Yeah, I can go back and do this.’ No, it’s just debt.”

While conducting my interviews, one thing became clear. Debt makes daily life harder. But it also haunts teachers inside their classrooms, impacting their pedagogical practice. Some teachers, fearful of job loss and the subsequent inability to pay back loans, alter how and what they teach. They become more conservative when designing curriculum, or when teaching hot-button issues. Other teachers suffer from anxiety and depression brought on by the debts they owe. For these indebted teachers, sometimes it’s a struggle to just make it to class day in and day out.

Debt imposes more labor on overburdened teachers. Nitzelis remarked during our conversation that she often holds down multiple jobs to pay her bills. She’s not alone. According to a 2022 EdSource article by Karen D’Souza, “In a 2021 national survey of 1,200 classroom teachers conducted by the Teacher Salary Project, a nonpartisan organization, 82 percent of respondents said they either currently or previously had taken on multiple jobs to make ends meet. Of those, 53 percent said they were currently working multiple jobs, including 17 percent who held jobs unrelated to teaching.” It seems fair to assume that teachers would not work so many hours if they had less debt to service.

Many teachers decide that teaching with massive debt burdens isn’t worth it. Over time, the unjust reality of low pay and high debt, often incurred from taking graduate classes to maintain certification and/or acquire advanced degrees, leads to burnout and decreases in teacher retention. As the Center for American Progress notes, not only does debt keep many students from entering the teaching profession, it also forces them out. Teacher retention levels for those with debt, especially BIPOC teachers, are lower than for teachers without debt.

Like other crises in U.S. public education, teacher debt reveals how years of neoliberal higher education policy has utterly failed teachers. While corporations and wealthy individuals received tax breaks, funding for higher education was drastically cut. As noted by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, deep state cuts for higher education funding have contributed to rapid, significant tuition increases. On average, between 2008 and 2018 states spent $1,220, or 13 percent, less per student while tuition at four-year colleges has risen by $2,708, or 37 percent. Students have been driven into debt to make up the difference. Those living debt-free, and even some with debt, ignore this fact and often preach debt payment as a sacred obligation. According to this ethical calculus, if you took out a loan you must pay it back, no matter the conditions that forced you into it, or the conditions of your current indebted life.

The teacher debt crisis reveals this logic’s perversity. Teachers give their all to schools, their communities, and students, and in return they get buried in debt. Talking with teachers like Richelle and Nitzelis makes us ask, “Who owes what to whom?” Or as Richelle put it, “We [teachers] give all of us, all of our existence to schools, and we get very little in return.” Reformist half-measures like Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) have largely failed to give Richelle and other indebted teachers their due. Though the Biden administration has improved this program, the jury is still out on how it will help teachers with debt in the long run. PSLF’s track record isn’t promising. According to the NEA, since 2017, the beginning of PSLF, 98 percent of applicants for loan forgiveness have been denied.

There are other options for dealing with the student debt crisis. When the U.S. Department of Education was first given the power to issue and collect student loans in 1958 it also received the power to “compromise, waive, or release any right” to collect on them, according to activist researchers from Debt Collective. President Biden could ask the Department of Education to use this compromise-and-settlement authority and then sign off on the cancellation of all federal student loan debt. If enacted, far fewer teachers would have to put in the time to receive — and live with the anxiety of being granted — PSLF.

Accompanying the material struggle that comes with an indebted life is the social stigma teachers face. “It’s like, people laugh at us,” Richelle remarked with dignified rage. Rather than ask how they can make educators’ lives better, more Americans than we’d like to admit question why someone would dedicate their life to teaching in these indebted times. Richelle said: “When we talk about our student loan debt to people who for example have business majors, they’re like, ‘Well, why would you go to college to become a teacher if you couldn’t afford it?’” For Richelle, “[This is] like a slap in the face.”

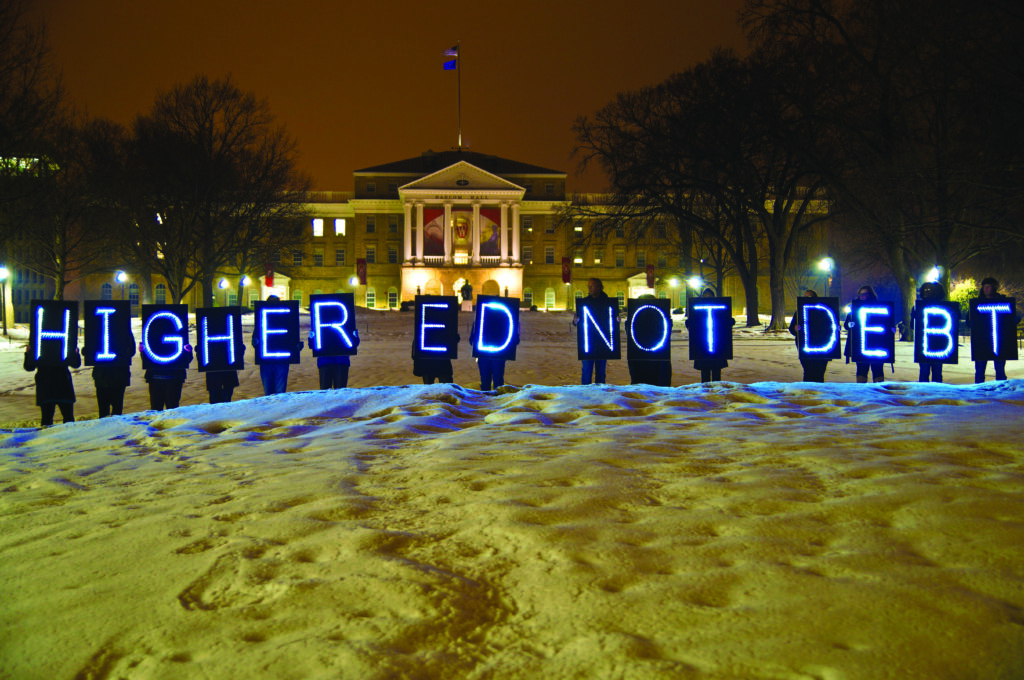

But many teachers I’ve met are fighting back; they’ve had enough. Buoyed by student debt movements and groups like Debt Collective, the nation’s first debtors’ union I organize with, more and more teachers are saying, “Can’t pay, won’t pay!” They are naming the student debt crisis. By doing as Richelle does — “I’m naming my inability to pay this debt and politicizing it” — teachers are passing on an important lesson: Things don’t have to be this way. As Richelle said, “In a country where education should be a public good, why isn’t it free, especially for Black and Brown folks?”

No teacher should have education debt. Existing debts should be abolished, and higher education should be free. But how can we reach such emancipatory horizons? Drawing inspiration from unions like the Chicago Teachers Union and United Teachers Los Angeles, and from the struggle for better wages, benefits, and working conditions led by teachers and community members in West Virginia, Oklahoma, and elsewhere, groups like Debt Collective have begun to bring debtors together to demand debt cancellation. They recognize, like other unions, that working-class intersectional prolonged struggle is the only path toward debt liberation. As Richelle remarked toward the end of our discussion, “We [need to] come together as a collective, and say, since we can’t pay it, we’re not paying it. And if enough of us come together and do that, then that’s when we effect change.”

In fact, President Biden’s recent student debt cancellation decree might not even have happened if teacher unions had not pressured the White House to abolish debt. Unions like CTU and UTLA passed resolutions calling for full debt cancellation. Teachers joined protests. And parent and student groups like the Philadelphia Student Union demanded that no one should carry the burden of education debt, certainly not the teachers providing communities with educational opportunities.

Debt cancellation efforts in Puerto Rico also serve as examples of the type of cross-sector collective mobilization we need to cultivate. For years, activist groups like AgitArte, the Federación de Maestros, and K–12 and university student groups along with other community members have built bonds of solidarity by creating popular political education campaigns, mutual aid networks, and packing stadiums and the streets to protest against debt. On the mainland United States, Debt Collective has made popular the practice of holding debtors’ assemblies. As debtors tell their debt stories to others in similar situations, they realize that they are not alone and discover their collective power to challenge creditors of all types.

As we listen to debtors’ stories, it becomes clear that debt is a labor issue. It imposes more work, robs free time, chips away at salary increases, hurts teacher morale, and fosters all sorts of educational harms. Cancelling teacher debt isn’t good just for teacher pocketbooks, it’s also good for those learning from teachers. When teachers are well paid and debt-free, they have more time to dedicate to serving students, communities, and taking care of themselves and their loved ones.

We need to make sure that our teacher, staff, and administrative unions put debt on the bargaining table and think of debt demands as part of Bargaining for the Common Good (BCG). To abolish education debt, we need to build a coalition K–Higher Education union movement that works with parents, higher education students, and the K–12 students who will one day accumulate college debts of their own if we don’t act with urgency.

As we discussed this article, my dear friend, comrade, and co-conspirator Eleni Schirmer invoked years of sadness and tears to my eyes with a question that I’ve grappled with since joining Debt Collective: “What if your father didn’t wrestle with his debts in the dark of night, but stood arm in arm with other debtors, denouncing them in the light of day?” I’ll never know. But I’d like to think that he wouldn’t have lived his last moments worrying about his loans. For him, Richelle, Nitzelis, and other indebted teachers like them, debtors must unite to fight for debt liberation.