How School Lunch Debt Creates Shame and Inequality — and Our Fight to Abolish It

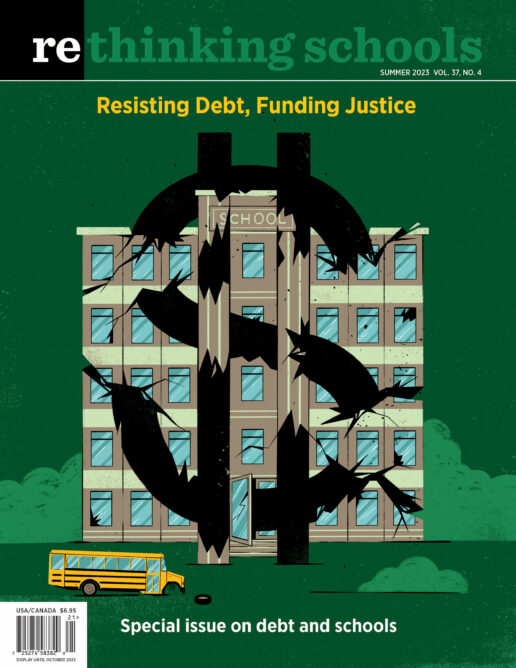

Illustrator: Ewan White

When Vincent Montoya-Armanios was in grade school he could not always afford lunch. School staff singled him out in the lunch line when he could not pay and told him to “speak to the manager.” The manager demanded to know why Vincent did not have money for lunch before letting him eat.

This happened to Vincent in the 2010s in Pennsylvania. Today, more than 1.5 million students nationwide have school lunch debt and continue to face barriers to eating at school. Rather than provide free lunch as part of public education, the government has shifted the onus to individual families. This saddles families who cannot afford lunch with debt. Working-class families and families of color are disproportionately burdened with school lunch debt.

Too many consider debt a moral failing in our individualist and capitalist society. Our society has relied on individual and piecemeal donations to address this issue. But we need to organize to make sure that school lunches are treated as a public right. Universal free school meals alongside debt abolition would ensure that students are fed at school and freed from the burdens of lunch debt. We have waged a campaign based on these principles in Bucks County, and found that organizing can be successful.

What Is School Lunch Debt?

Some students carry debt simply for being unable to afford school lunch. The annual national public school meal debt is approximately $262 million. More than 75 percent of schools record meal debts. With inflation, supply chain issues, and staffing shortages, the cost of a school lunch today can be as high as four or five dollars, nearly twice as much as in 2017.

Meanwhile, the threshold to qualify for free or reduced lunch through the federal National School Lunch Program (NSLP) excludes many families who cannot afford lunch for their kids. For the 2022–23 school year, a family of four is eligible for free lunch only if family income is at or below $36,075 a year and is eligible for reduced lunch if family income is at or below $51,338. As many as one in five students who are food insecure live in a home ineligible for free or reduced meals.

The Bucks Cancel Lunch Debt Coalition

After hearing about this issue, Pennsylvania Debt Collective approached organizers in Bucks County, including those in BuxMont DSA and Lower Bucks for Change, about addressing lunch debt in our area. The Bucks Cancel Lunch Debt Coalition (BCLDC) held its first meeting in May 2021 and set a goal: eradicate school lunch debt and implement free meal programs. We began to research the debt students held in our area schools.

We learned that for some school districts, corporations like Giant, a grocery store chain, had erased the debt through donations. However, if not paired with universal free meal programs, the cycle of lunch debt will continue to trap students’ families.

This issue was personal to us. For instance, Nick shared his experience with a fluctuating financial situation in high school, which meant that one year he might qualify for free lunch and the next year he might not: “Knowing that my father, unemployed at the time, probably felt shame to see his kids receive free lunch made me feel similarly ashamed. I questioned if I was really deserving of free lunch when others probably have way less than I,” Nick said. “The shame and stigma I felt was something I don’t want others to feel.”

Barriers to Accessing Free Lunch

Participation in NSLP is based on family income through “means testing” — limiting eligibility for a specific program, service, or benefit to individuals or families based on their means or resources. Across society, programs, services, and benefits, such as public libraries and public schools, are free without any means testing, while other services, like school meals, are not. A child at a public school does not need to bring $5 to their teacher each day to use the school bus or to pay for their textbook. There is no income level cutoff for these aspects of public education, yet there is for school lunches.

Meanwhile, the application for NSLP can be burdensome. First, there is the application process itself, which requires knowing NSLP exists and then completing multiple forms requesting proof of income. Tolulope Olaniyan, now in her 20s, had lunch debt while in 7th grade in North Carolina. “I wish my parents knew about [NSLP] or how to access resources like this as a struggling immigrant family,” she reflects now.

Second, there is the stigma associated with free meals. Tolulope noted that free meals come with the stigma that parents are failing to fulfill a duty to provide for their children by receiving federal assistance. “Universal meals would have removed any stigma associated with lunch debt or being a part of the free or reduced lunch program and would have been one less thing for my family to worry about,” Tolulope said.

The Case for Universal Free Meals

Instead of ensuring every student free meals, the United States relies on charity “fixes” — short-term food drives, community food pantries, corporate donations to pay for lunch debt. Although generous, these efforts do nothing to ensure students are not burdened with school lunch debt and put off solving the core structural problem of the issue: School meals are a right, yet are not treated as such.

There is precedent for publicly funding school lunches. The Community Eligibility Provision (CEP), operated by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), permits schools to give every student free meals if the number of households participating in federal welfare programs is at least 40 percent of families. School districts such as Philadelphia, New York, Atlanta, Los Angeles, and Houston are enrolled in CEP. However, more than half of eligible schools choose not to enroll because the rate of meal reimbursement from the federal government may not make it financially feasible.

When the COVID-19 pandemic started, Congress and the USDA ensured school meals would be free for all; families did not have to prove need to receive this public benefit. Every student, regardless of income, received free school meals. Unfortunately, this program ended in June 2022 when Republicans opposed continuing the program, which cost about $11 billion annually, less than .2 percent of 2022 federal spending.

California, Maine, Colorado, and Minnesota recently passed legislation to do what the federal government has not: fund free breakfasts and lunches for all public school students, regardless of family income.

In states without universal free school meals, schools are prohibited from using federal reimbursement funds for food service to write off lunch debt, causing schools to look to outside charities, general district funds, parent teacher associations, and families to pay off this debt. Schools in resource‑scarce areas suffer the most. This structure disproportionately impacts students of color, overrepresented in resource-scarce schools and areas. As legal scholar Abbye Atkinson explains in her article “Philando Castile, State Violence, and School Lunch Debt: A Meditation,” “Financial insecurity is racialized and gendered, and by design, its alleviation is increasingly meant to be borne by private citizens in our American public-private welfare regime. The phenomenon of school lunch debt, including its significant reliance on private sources of repayment, is emblematic of this reality.” Atkinson goes on to note that this burden is therefore carried “by those who survive in the liminal, vulnerable spaces between abject poverty and financial security.”

Taylor, a lead cook at an Indianapolis elementary school, who asked to remain anonymous out of fear of losing her job, echoed these disproportionate impacts on students of color, noting that most students she speaks with about their negative lunch balances are Black and young people of color from working-class families with parents working two or three jobs. Absent larger structural solutions to this issue, lunch debt will continue to disproportionately impact students of color and students from working-class families.

Lunch Debt Shame

Although 80 percent of Americans have consumer debt with an average of $96,371 per household, and about half of families live paycheck to paycheck, people seem hesitant to talk about debt, which makes developing collective power difficult.

Too many people in our society consider debt a moral failing. Schools reinforce this sense of moral failing through “lunch shaming,” a term for when a school embarrasses or punishes a student with a negative meal balance. Vincent felt embarrassed and humiliated when he was singled out in front of friends and sent to the manager’s office. This humiliation scared him. And other kids watching would be unlikely to attempt to eat at school again without money for lunch. Tolulope was in line with her peers when staff told her that she “couldn’t get the hot meal” and would have to get a cold sandwich instead because she had a negative account balance. “It was a very public moment with my classmates right behind me in line. I wish it had been handled better and privately,” she reflects now. She often skipped lunch rather than subject herself to this embarrassment. Even when she skipped lunch, however, school authorities still forced her to sit in the lunchroom. Taylor often sees students’ faces fall when they do not have enough money in their account to get a hot meal and instead have to get a peanut butter and jelly sandwich.

Some schools shame students like Tolulope by giving out alternative lunches such as tuna or peanut butter and jelly sandwiches rather than hot meals like pasta, hamburgers, or pizza. Some schools, like Vincent’s, tell students they cannot attend field trips or walk at graduation if they have lunch debt. One Pennsylvania school district threatened to put students in foster care when their parents had not paid their lunch debt. Schools shame students for financial situations outside of their control and deny students opportunities that should be part of their public education.

The Ripple Effects of Lunch Debt

It is not only students who are affected by lunch debt. Emily Stone, a Pennsylvania high school teacher, buys snacks and granola bars so that her students always have something to eat. When Jessica Pierce was a South Carolina elementary teacher, she saw her students stress over whether they had enough money for lunch. When they could afford a meal or received a free lunch, they would usually devour it because it was the only meal they had all day. She made sure to have crackers and granola bars at her desk for when one of her students was hungry.

Then there is Philando Castile, nationally known as the victim of state murder after a police officer killed him during a 2016 traffic stop. But to those in his community in St. Paul, Minnesota, Castile was a beloved cafeteria supervisor, colleague, and friend. Castile worked at a magnet school for more than a decade until his death and often used his own funds to pay off his students’ meal debts. After his murder, his mother, Valerie Castile, gave $8,000 on behalf of the Philando Castile Relief Foundation to write off lunch debt at Robbinsdale Cooper High School in New Hope, Minnesota.

One district threatened to put students in foster care when their parents had not paid their lunch debt.

The current lunch debt system leads to teachers and staff, often underpaid themselves, to use their own money to ensure students do not go hungry. Others, like Taylor, may risk their job by paying for a student’s meal against school policy. “The hardest part of my job is choosing between giving a kid a hot meal when they cannot afford it or putting my job at risk,” Taylor said.

The cycle of hunger and debt adds to the many demands on overworked educators and inhibits students’ ability to learn. The Food Research & Action Center reports that “[b]ehavioral, emotional, and mental health, and academic problems are more prevalent among children and adolescents struggling with hunger.” This adds challenges to teachers in educating and caring for each student and hinders students’ abilities to engage in meaningful education. As Atkinson puts it, “[G]iven the significance of effective education to the development of marginalized communities, and in turn the significance of food and nutrition to effective education,” school lunch debt is a critical racial and social justice issue.

Lunch debt has material and psychological consequences. “Looking back, I cannot understand how I got through 7th grade,” Tolulope reflected. “I was often hungry throughout the day, and the only reason I could focus was that I knew I was lucky enough that I would have some kind of food once I got back home.” As Vincent put it, lunch debt means that “[t]he shame, instability, and indignity of poverty is instilled in American youth before they can even work for a wage.”

BCLDC’s Campaign

In beginning our campaign, BCLDC chose to focus on Bristol Borough School District (BBSD), a small district in a town of about 10,000 residents, centrally located for our organizers. In the 2021–22 school year, 212 students held more than $15,000 in debt at BBSD.

Thanks to funds from Debt Collective — a national debtors’ union that organizes to cancel various forms of debt — we centered our demand around building community relationships, emphasizing “We have the money, we just need people.” We intended to use this money to bargain with the district to buy the debt for pennies on the dollar and then cancel it, since we predicted the district would rather recoup some of the debt than have it remain perpetually outstanding. We hoped to develop local community organizing to pressure the district to cancel the debt and provide universal free meals so students are fed and debt-free.

Building this collective power to cancel the debt became the overarching strategy as we searched for community members willing to tell their stories with lunch debt. Despite our efforts to provide a welcoming space of and for working-class debtors, it proved challenging to encourage people to publicly share their stories of lunch debt. Unlike labor or tenant organizing that can be centered around a common place such as a workplace or an apartment building, debtors may not be in direct community with each other. In an effort to build conversation and destigmatize debt, we wrote an op-ed for a local publication to try to shift thinking in favor of cancellation, rather than a “bootstrap,” individualist mentality.

In September 2021, BCLDC held a Debt Assembly in a Bristol Borough park. We emailed BBSD teachers, passed out flyers in busy areas, and promoted it on social media. Organizers made the moral case for lunch debt eradication while community members, a number of them educators, provided moving testimonies.

A Lunch Debt Cancellation Victory

In February of 2022, two of the authors of this article attended a board meeting to raise lunch debt in BBSD. We advocated that the board cancel the debt, and announced that we would escalate our campaign for cancellation if lunch debt remained on the books.

To our pleasant surprise, the board agreed that lunch debt was an issue and announced publicly for the first time that it would cancel that debt. Bargaining to buy the debt was not even necessary. Our campaign efforts, including nine months of meeting, planning, holding a Debt Assembly, using the local press, and reaching out to various community members, had moved the district toward cancellation. As the board president, David Chichilitti, later remarked to the press: “This got lost in the pile until they mentioned it to us.” On August 30, 2022, BBSD officially notified families that it had canceled all prior lunch debt.

Free Meals for All

We hope this campaign will inspire others as we seek to expand debt cancellation and fight for debt abolition. Leaving this problem to charities allows private organizations to exclude people who decision makers deem “undesirable” or “unfit for assistance.” It also positions corporations, who pay for the lunch debt, as benefactors and ignores the efforts by educators, cafeteria staff, and others who ensure students are fed. Although it is important to improve conditions as we fight for structural change, these donations do not confront the bigger problem. Until school meals are publicly funded and universally provided, families will struggle, and the cycle of debt and charitable donations will continue.

This will involve long-term and multipronged fights at the national, state, and local levels. At the federal level, Senator Bernie Sanders previously introduced the Universal School Meals Program Act of 2021, SB 1530, and Representative Ilhan Omar previously introduced the same in the House, HR 3115, both of which are set to be reintroduced in this new session of Congress. This act would cancel all school lunch debt and ensure all schoolchildren receive free school meals regardless of family income.

At the state level, teacher unions, organizations, and coalitions can fight for legislation to implement programs that ensure universal free meals at public schools like those recently instituted in California, Maine, Colorado, and Minnesota. At the local level, we owe it to each other and our students to organize and mobilize our communities to demand that schools cancel debt, opt in to CEP when eligible, and advocate for universal free meals. Community members need to discuss the issue of school lunch debt and food insecurity at local school, municipal, and county board meetings, and with community groups and neighbors.

Following the BBSD cancellation victory, we decided the best way forward was to build partnerships with others doing this work across Pennsylvania. We met with State Senator Lindsey Williams and Representative Emily Kinkead while they were planning to introduce bills for universal school meals. We successfully lobbied for the senator and the bill’s co-sponsors to include $25 million in universal lunch debt cancellation in the proposed bills, which have since been introduced as SB 180 and HB 180. The senator organized a meeting of stakeholders, including Pennsylvania Farm to School Network, Just Harvest, the School Nutrition Association, the Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank, BCLDC, superintendents, and educators.

We also decided to change our name to the Pennsylvania Cancel Lunch Debt Coalition (PCLDC) to expand our coalition and broaden our base as we seek to bring more people into the fight. In March 2023, we held a statewide virtual Debt Assembly in conjunction with the senator’s office to build our base and pressure our elected officials to support universal school meal legislation and incorporate funding in the state budget.

Together we can ensure that no student must choose between lunch at school or putting their family in debt. All students should learn and grow free from the burdens of food insecurity and lunch debt.