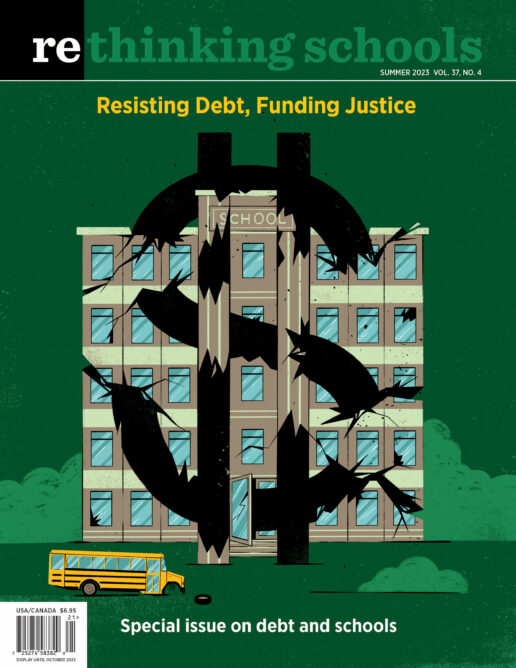

School Debt: The Great Unequalizer

Illustrator: Brian Stauffer

In January 2020, mere weeks before the COVID pandemic shut down the world, Philadelphia schoolteachers bundled up and planted themselves in front of Lewis Elkin Elementary School. They were refusing to enter the building. A recent report had revealed unsafe levels of asbestos in the school, and the district had yet to confirm safe test results; a veteran teacher at another school is dying from mesothelioma. Lead paint flakes through the district, poisoning children while sitting at their desks. Freda Anderson, a Philadelphia high school teacher, tells me she used to believe the best way to fix schools would be to hire more teachers, counselors, and mental health providers, “but, honestly, now the first thing I would do is start reallocating money to fix the buildings. They’re just really dangerous.” Anderson, an alum of Philadelphia public schools, is no stranger to school funding shortages. For the last decade, the city’s per-pupil revenue has been in sharp decline; an independent audit revealed $4.5 billion of unmet infrastructure needs. What’s more, the state’s school funding system was recently deemed unconstitutional; its distribution mechanism discriminates against students who live in low-wealth districts, like Philadelphia.

Underfunded schools are bad enough. But without adequate funds, school districts increasingly must borrow millions of dollars, provoking a massive increase in debt-laden schools. Poor communities of color are driven into the arms of Wall Street creditors thanks to racialized school funding formulas. In the short term, debt may help schools fill budget shortfalls caused by insufficient funding. But in the long term, debt exacerbates existing inequalities and extracts resources. Poorer schools pay more in interest and fees, and are often forced to make draconian budget cuts in order to do so. In the absence of adequate progressive and democratic school funding, debt is offered as a lifeline. It can quickly become a noose.

Far more than a sum of dollars and cents, debt constitutes a power relationship. Debt enables creditors to direct priorities, determining who and what gets funded. While districts pay millions in debt service, school buildings deteriorate and educators’ wages dampen. Yet debt is rarely, if ever, discussed in political terms. Instead, it’s often considered neutrally, a necessary backstop for chronically underfunded schools. But debt has pernicious consequences of its own — further expanding school inequities.

Over the last century, the United States has shifted away from tax revenue to fund its public services — from health care to higher education — to borrowing. Since the 1970s, wealthy households and corporations have paid significantly less portions of taxes; today, the corporate tax rate on billionaires is lower than the tax rate of the working class. To make up for the resulting budget shortfalls, state and local governments take on debt. The state and local government debt loads increased from $1.2 trillion in 2001 to $3.1 trillion in 2022. This burden shifts onto households, in addition to state and municipal government. People have to borrow money to pay for health care and college, for the car they need to get to work, for housing. In 2022, the level of U.S. household debt hit more than $16.5 trillion, nearly doubled from 2004. The U.S. welfare state, once funded by taxes, now runs on debt.

From top to bottom, the very walls of the schoolhouse are saddled with debt. In 2019, K–12 school debt reached nearly $500 billion, a 118 percent increase since 2002. The debt service on this massive and growing debt — the principal payments, interests and fees associated with borrowing — sends increasing amounts of school dollars to banks and financial institutions. In 2021, the Philly schools paid $311 million to service its debt — 9.2 percent of its annual budget. More than half of that — $162 million — went to Wall Street creditors as interest payments.

When school funding formulas fail to provide sufficient resources for schools, the district (or municipality) has to go to the bond market to issue a bond. A bond is basically a big, complicated, legally binding IOU. Financial investors buy the bond and give the school district the cash they need. In exchange, the school district pledges to pay the financial investors back over the next several decades — plus interest and fees, set according to the district’s credit rating. A credit rating is a metric used by investors to determine how likely a borrower is to default (or not pay back) on the loan they made. Low credit ratings mean a borrower is considered “risky.” Investors demand higher interest and fees to lend money to these supposed “riskier” borrowers.

Moody’s Investors Service, a preeminent credit rating agency, for example, bases a school district’s credit score on the district’s existing property value and residential income — the more working class the neighborhood, the worse their credit rating. This means poorer schools face higher interest rates; greater portions of their resources get shuttled into fees and payments to Wall Street banks. Credit ratings rely on data metrics — a neighborhood’s housing values, employment rates, incomes — left in the wake of a past structured by racism. Credit rating agencies base their calculations on these factors, carrying racist, historic patterns into the future. Cities and school districts with majority residents of color routinely suffer the worst ratings — entire communities given bond ratings’ lowest score, known as “junk.”

The consequences are grave. Paterson, New Jersey’s public schools, which enroll 95 percent students of color, pay more than 60 percent more in fees than the neighboring, predominantly white school district of Fair Lawn. In Mississippi’s Claiborne County, where 55 percent of children live below the poverty line, the school district pays 94 percent more in borrowing fees than the neighboring Hinds County, where merely 14 percent of children live below the poverty line. The long, intertwined history of racial domination and economic exploitation means that Black and Brown families have less wealth, and typically live in communities with lower property values. Because much school funding comes from property taxes, districts with the lowest property values face the largest budget shortfalls, and therefore the most need to borrow money. But these districts face higher borrowing costs. The logic of credit punishes districts who already face funding shortfalls.

This process is steeped in racism, affecting even a district’s ability to issue bonds in the first place. Municipal bonds typically require voter approval; bonds often mandate that voters agree to increase taxes as collateral for the bond. But this measure is fraught with racist notions of who is deserving of public services, and who is willing to pay for them. Older, white voters are less likely to approve bond referenda to fund public infrastructure, such as public schools, in predominantly Black neighborhoods. In effect, this has made municipal bond financing, in the words of historian Destin Jenkins, an “infrastructural investment in whiteness.”

For many poor, predominantly Black school districts, the mere hope of adequate facilities remains out of reach. Today, school districts that serve high-poverty students have the most buildings with critical repair needs. To update air ventilation systems, repair poor lighting, or replace lead pipes, school districts must ask voters to approve measures to increase taxes as backing for the necessary bonds. And as history shows, if repairs or renovations are for Black schools, voters are less likely to approve the measure. When schools are forced to rely on debt to secure safe operations, poor communities of color lose the most.

The debt cycle is a punitive one.

School districts with the fewest resources pay the most to borrow. As a result, the debt cycle is a punitive one. If a district faces economic hardship, such as a major regional employer closing shop, not only does the district lose income, making it more reliant on debt, but its credit rating plummets, making such borrowing more expensive. Similarly, if a region is susceptible to flooding, hurricanes, forest fires, or other ravages of climate disasters, creditors charge more interest and fees. For underfunded school districts on the brink, relying on credit entrenches further harms.

Creditors don’t determine only the amount of money a district can borrow, but attach conditions that mandate how much of a city’s budget must go to debt service payments rather than, say, replacing lead-crusted windows or hiring more social workers. A low credit rating may discourage a city from taking on capital-intensive projects, like building new schools, replacing ventilation systems in old buildings, or making climate adaptations. As a result, public schools in poor cities suffer from neglected, even toxic, infrastructure. In pursuit of higher credit ratings, school districts often close schools, lay off employees, and privatize services. Creditors can even invoke the right to “intercept” a school district’s state aid if it falls behind on its payments. Furthermore, creditors and credit rating agencies often penalize districts that have smaller reserve funds — which are, effectively, saving accounts — pressuring districts to cut personnel and programs in order to plump up their reserves.

Loan payments are often set years in advance — well before staffing levels or wages are set. In 2013, Chicago Public Schools closed 50 schools; that same year, it paid more than $300 million in interest on its debt service, which had increased 22 percent from the previous year. In 2016, after school closures and budget cuts failed to solve the Chicago Public Schools’ budget crisis, the school district borrowed another $725 million — not to reopen schools or hire more educators, but to service its debt. More recently, Chicago’s then-mayor, Lori Lightfoot, used federal money earmarked for the city’s COVID relief to make debt service payments. Perhaps most astonishingly, in summer 2022, the Biden administration sued Rochester, New York, for “rampantly overspending on teacher salaries,” and misleading bond investors about it. The school district, which enrolls 90 percent students of color and 47 percent students who live in poverty, has been drastically underfunded by the state’s school aid. A $50 million budget shortfall prompted the district to borrow funds from the bond market. But when teachers got paid before investors, the federal government’s Wall Street regulatory agency, the Securities and Exchange Commission, sued the school district.

In the face of decades of funding shortfalls, school districts like Pennsylvania’s Wilkes-Barre closed two high schools, furloughed teaching staff, and laid off librarians. These cuts enabled the district to generate a $2 million capital reserve fund, upgrading its credit rating from “negative” to “stable.” But at what cost? As the superintendent explained, “Although our finances on a sheet of paper are absolutely much better than they were when we were facing a $70 million deficit, there’s been a great cost to our district in an already stricken district.” In fact, the judge who recently ruled that Pennsylvania’s school funding system was unconstitutional argued that the demands of creditors and credit rating agencies often override a school district’s capacity for “local control.” Can there be meaningful local control in a system in which schools increasingly rely on private investors for their resources?

As the 2008 recession crumpled state and city revenues, many school districts, under the guidance of so-called financial experts, turned to the fashionable investment mechanisms of variable bonds and interest swaps to secure funds the state would not provide. But as interest rates dropped, these deals turned toxic, leaving cash-strapped districts on the hook for high premiums. Schools and taxpayers in urban and rural districts lost millions. In 2010, Philadelphia public schools paid $63 million in fees simply to extricate itself from some of its toxic swaps — more than it spent on books or supplies that year. Chicago Public Schools lost more than $600 million in toxic debt swaps. In both Chicago and Philadelphia, budget shortfalls prompted school administrators to close dozens of neighborhood schools in Black and Brown communities, disproportionately stripping communities of color of a vital public institution.

Debt financing isn’t simply expensive — it also encroaches on democratic governance. Although voters may decide whether or not bonds are taken out, they have little to no say over the actual terms of the bonds — who lends the money, at what interest rates, with what punishments in case of nonpayment. Even the most progressive, social justice-minded school board in the country will face steep challenges to fulfill its goals as long as the underlying system relies on the existing rules of debt. When a district is first and foremost beholden to private creditors and credit rating agencies, all the local control and friendly PTAs in the world can only do so much.

Building on the legacy of struggles for fair school funding, communities are beginning to organize to challenge rule by debt. In Chicago and Los Angeles, public sector unions have taken up campaigns to challenge interest rates that bleed the public dry for Wall Street’s gain. But the work is not easy. Because of the notorious self-blame around debt — we got ourselves into this, so we deserve this suffering — organizing requires deep re-education. Although school districts might not be blamed in the same way individuals are for taking on debt, any attempt to refuse payment to creditors would be met with swift condemnation. Much of the work, therefore, is to delegitimate the ethical framework that says debt’s anti-democratic power relations are OK. An important part of that work is to draw attention to the fact that the basic architecture of debt is often obfuscating and confusing. It’s hard to politicize an issue that makes people either fall asleep or feel stupid. Too often, debt gets rendered as a problem of dollars and cents rather than its more fundamental axis: power. Denaturalizing its essential plotline is a first step to challenge the rule of debt.

A second step is to lean into both the pragmatic and the utopian alternatives to running schools on debt. For example, while the federal government provides only a small percentage of the funding for K–12 public schools, it could at least provide some of the same financing supports it has made available to banks and corporations. During COVID, for instance, the Federal Reserve provided zero-interest loans to corporations to stave off financial collapse in the private market. A federal lending facility that provided better alternatives to Wall Street’s deals — such as zero percent interest loans — would reduce the need for school districts to hustle for Wall Street funds. Federal financing would allow schools to sustainably invest in reparative projects — fix damaged infrastructure, reduce class sizes, refurbish healthy green schools. (There are some such mechanisms in the climate provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act passed last year.) Expanding such supports would help schools move beyond one-time budget injections. Without transforming school funding mechanisms, schools remain vulnerable to the next recession, the vagaries of business cycles, and the prejudices of Wall Street creditors.

After all, it’s neither students’ nor educators’ fault that schools have not had sufficient funds — yet they’re the ones paying the price. For educators and organizers, the task isn’t simply to imagine another world, but also to install the democratic, reparative financial infrastructure to support it. Imagine teacher unions that bargain over credit ratings or repayment terms. A social justice union with a debt analysis could demand that investors get repaid only after solar panels have been installed, gardens grown, wages made livable, class sizes shrunk, and classrooms beautified. An analysis of debt may help deepen and unify struggles against budget cuts, racist school funding formulas, and underpaid educators.

Debt is the heartbeat of austerity, the electrical pulses that direct funding slashes and prioritize Wall Street payments over people’s health and safety. Movements that aim for robust, reparative, democratic public education must keep the debt economy in its sights. If public schools are mythically hailed as the great equalizer, consider debt as the great unequalizer: It punishes those with the least, while rewarding those with the most. A school system held hostage to debt can hardly fulfill its mission. Social justice educators must take note.