“You’re to Blame”: How Financial Literacy Curricula Make Students Financially Illiterate

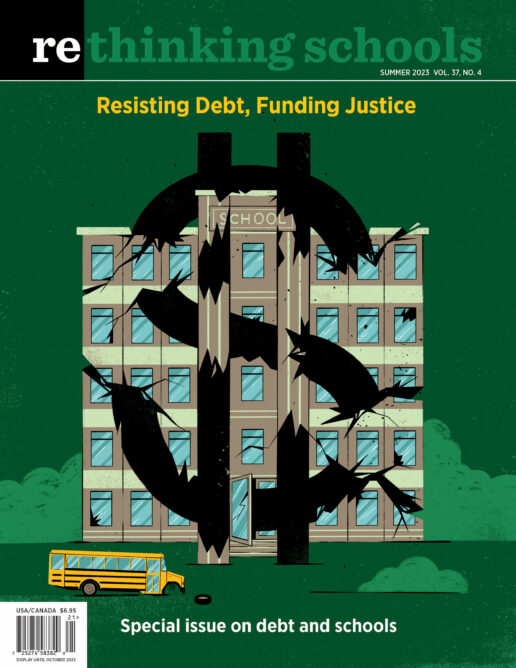

Illustrator: Christiane Grauert

As a high school social studies teacher, I’ve seen an increasing push to require financial literacy or what used to be called “personal finance” in schools. These courses cover budgeting, understanding credit and interest, tax forms, and savings, but now include a bigger focus on paying for college and student debt. These curricula rest on the neoclassical economic paradigm that centers individual choices in the market, which is supposed to be minimally regulated — to be free and efficient.

No doubt, our students do need to learn about their personal finances. The problem is that many financial literacy curricula ultimately blame individuals for systemic problems, reinforcing an assumption that our capitalist political economy is a meritocracy, and that people exploited and oppressed must have a deficit of knowledge, intelligence, morality, or discipline — as if people become millionaires by skipping lattes to invest in stocks.

Such programs are especially pushed by powerful corporate lobbies from the U.S. Chamber of Commerce to the American Legislative Exchange Council and tend to be sponsored by Wall Street financial institutions. Junior Achievement has been a mainstay for pushing neoclassical economics and an early promoter of financial literacy, offering trained volunteers from corporations like Kraft Foods with curriculum sponsored by UPS, ExxonMobil, Goldman Sachs, and New York Life Insurance to take over the teaching of an economics course for days, if not weeks, for free. These outfits have no more desire to help students think critically about our economic system than the coal industry wants youngsters to recognize the fossil fuel roots of the climate crisis.

As of the fall of 2022, 37 states had legislation for financial literacy education in schools. Advocates pushed to standardize and make this type of economics a high school graduation requirement beginning in the late 1980s, but pressure for them from capitalist interests has increased with each economic crisis. Scholar Max Haiven writes that the push for financial literacy education increased after the 2008 global financial meltdown, and argues that “they typically produce a profound financial illiteracy by obfuscating the systemic and structural dimensions of debt, financial hardship, and the patterns of financialization, thus reaffirming a neoliberal trend to privatize social problems.”

The rationales for these programs suggest a need to redirect responsibility for economic crises. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), created after Wall Street banks crashed the global economy and U.S. regulators pronounced that the culprits were too big to fail or jail, cites data from the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), which first added a financial literacy test in 2012, to claim a gap in financial literacy similar to the achievement gaps cited by corporate education reformers.

Likewise, financial literacy programs seem primarily directed at socioeconomically disadvantaged students, with a false solution to growing precarity and indebtedness of young people, as wages have been stagnant, public services and safety nets have been cut, and the gig economy increasingly replaces better employment that offers pensions and health care benefits. Even with record numbers of youth attaining college and postgraduate degrees, most young people are worse off than previous generations. However, you would not know this from reviewing financial literacy curricula.

As a teacher, I want to empower students to look beyond the narrow framework and misleading information provided by these curricula. Instead of inviting students to see the world from the perspective of the owning class and to regard themselves solely as individuals, I want young people to recognize the injustices of the current system, the existence of alternatives, and the possibility of changing the world through collective action.

Invest in “Your Human Capital”

Financial literacy curricula position students as cogs within a fair capitalist machine, having only the power to rise — or fail — within a just system by conforming to its expectations. According to a financial literacy curriculum written by the Minnesota Council on Economic Education (MCEE) and the St. Louis Fed, differences in wages are determined by differences in productivity that result from differences in individual “human capital.” National Standards for Financial Literacy tell students that “Businesses are generally willing to pay more productive workers higher wages or salaries than less productive workers” and “Getting more education and learning new job skills can increase a person’s human capital and productivity.” A Grade 8 benchmark for the Voluntary National Content Standards in Economics states that “More productive workers are likely to be of greater value to employers and earn higher wages than less productive workers” — an assertion unsupported by the reality of the past 40 years, as wages have failed to keep pace with increases in productivity. Since curricula do not provide students this information, young people are unlikely to question the lesson’s validity, and are instead pressed to see low wages as the fault of workers who fail to follow the advice to “invest in yourself by developing your human capital — you need to ‘learn to earn.’”

The unit on “Entrepreneurship” focuses on “personal characteristics entrepreneurs are likely to possess” — including being “self-confident” and “willing to take risks” — suggesting that high wealth is a recompense for “productivity” and personal qualities, rather than a benefit of inheritance, social connections, or psychopathy within an unjust system. By the end of the lesson, students are supposed to have learned that “entrepreneurs take risks to develop new products and start new businesses. They are important to the economy because the new products they develop and new businesses they start create new jobs.”

Even those without the vaunted entrepreneurial qualities are encouraged to pursue college as a way of investing in themselves as “human capital,” rather than as a way to become more informed citizens or expand their understanding of the world. Charts graphing income against education level and occupation make the case for higher education, without mentioning “tuition,” “loan,” or “debt.” Also unmentioned are the experiences of the PhD adjunct professors living in their cars despite high investment in their human capital.

The MCEE/St. Louis Fed curriculum unit on “Earning Income” offers lessons on “Investing in Yourself” and “Entrepreneurship — Working for Yourself”; there is nothing on “Your Rights at Work,” “Joining or Starting a Union,” “Negotiating a Contract,” or anything related to how workers have successfully fought for higher incomes.

Identify with Bankers and Management

The interests of corporate promoters of financial literacy curricula run counter to those of the students at whom these programs are directed. Students today are encouraged to take on a record amount of debt to pay rising tuition that they are told is necessary for good jobs, while economic inequality is at levels unseen since the Gilded Age. Yet financial literacy curricula typically encourage students to consider not their own future indebtedness and precarious work, but the concerns of bankers and management, which are reduced to questions of profit. For example, the MCEE/St. Louis Fed curriculum on “Borrowing” has students complete an exercise in which they “play the role of credit providers” — compelling them to identify with lenders rather than borrowers — and omits any mention of compound interest or adjustable rates, two features of credit that can lead to crushing indebtedness.

Similarly, Junior Achievement curriculum teaches purely from the management perspective of a fictitious corporation, similar to Amazon, that goes from understanding the organizational hierarchy and proper corporate behaviors to please the executive team, to dealing with corporate policies and applying “conflict management techniques” in warehouse logistics. Students tackle problems like declining sales from management’s point of view. Yet management’s role in structuring working conditions gets written out of the curriculum. Junior Achievement does not help students grasp the nature of conflicts they are managing, in light of the fact that U.S. employers have near-dictatorial powers and Amazon forces drivers to consent to surveillance like biometric monitoring. The curriculum omits the struggles of exploited Amazon workers organizing to overcome the brutal conditions that force some to pee in water bottles and lead to injuries at twice the industry rate. And of course, there is no curricular mention of the successful fight to form the Amazon Labor Union — a story containing countless lessons for organizing today.

Financial literacy programs, most often sponsored by Wall Street banks, train young people to become consumers of the very services that they profit from, like using credit cards, maintaining a good credit score, and taking out loans. Yet they raise no issue about conflicts of interest and profit motives. For example, bankers and asset managers direct and fund the Council for Economic Education. Helaine Olen, in A Pound Foolish: Exposing the Dark Side of the Personal Finance Industry, shows how one of the early initiatives, Jump$tart Coalition for Personal Financial Literacy, began in 1995 with the vision of William E. Odom, chairman of the Ford Motor Credit Company, as delinquencies and defaults on subprime car loans cut into profits.

Financial literacy standards and curricula also focus on investing in stocks, bonds, and 401(k)s for retirement, as some of these same institutions lobby to privatize Social Security. The stock market is irrelevant for most of us, yet curricula offer no lessons on how workers have organized for better wages and benefits or how Canadians struggled for and won single-payer health care.

Emphasize Individual Choice Instead of Systemic Causes

Even before recent concerns about inflation with COVID and Ukraine conflict-fueled supply chain disruptions, costs of education, health care, and housing had been rising disproportionately. However, these economic burdens are less the result of bad individual budgeting or consumer choices, and more due to policy choices and capitalist exploitation. In fact, it is almost impossible to make good personal finance choices for something like health care, where choices are limited and prices are not transparent. However, exercises in hypothetical budgeting make it seem easy. For instance, the MCEE/St. Louis Fed curriculum offers a lesson on budgeting in which the cost of buying a new wardrobe every year equals the cost of health and dental insurance offering “complete coverage” — a mythical plan with presumably no deductible, co-pay, or prescription charges. Although every student in the exercise faces the automatic deduction of the same amount for taxes, students do not face a mandatory employer-sponsored plan; there is no opportunity cost calculation for the time, stress, and energy in choosing an individual plan; and the exercise omits downstream decisions about when to seek care or whether to ration one’s insulin.

Similarly, the housing crisis is systemic and individual choices are limited while discrimination continues for oppressed people in renting, purchasing, financing and refinancing homes, and the ongoing racist effects of earlier redlining continue. However, financial literacy curricula ignore such issues. In the MCEE/St. Louis Fed curriculum, although the “Wealth Game” divides students into poor, middle, and rich groups (with different numbers of beads for the exercise), the “Budgeting” portion presumes all students have the same choices in selecting housing. In addition, although the budgeting exercise includes a step where “inflation” or other circumstances deprive students of a portion of their allocated budget, forcing them to reallocate their resources, there is no consideration of the “fixed” cost of housing being raised; no one faces eviction or rent increases.

Dominant narratives center street crime, policing, and carceral systems but neglect the fact that employers’ theft of workers’ wages is not only common but affects more people, especially the most vulnerable, than all other crimes combined — and is three times as costly. For example, a curriculum from TD Bank, promoted by NEA, warns students about identity theft from people dumpster-diving through their trash but does not alert students to wage theft, urging young people to think as consumers, rather than as workers who might organize to keep more of the value they produce, or who might organize to change the rules and system. They also instill a There Is No Alternative assumption, neglecting both historic struggles and radical imagination for revolutionary transformation in an era of climate crisis.

What We Need to Teach Instead

In my high school political economy courses, I teach students that there are alternatives that exist now in countries with different policies. Germany, for instance, offers a better quality of life for most people with a social democracy that includes free tuition at public universities, universal health care, paid vacations, sick time, and parental leave, while achieving a higher productivity rate than the United States. And counter to the typical narrative that FDR saved America with the New Deal, my students learn that powerful labor and social movements won federal policies and programs that made most Americans more financially secure and that there is a struggle now for policies such as the Green New Deal and Quantitative Easing for Communities, which could radically change our economic lives. In my classes, we examine budget priorities on the federal, state, and local levels that benefit the military-industrial complex. We also discuss how most states had tuition-free public universities until the 1960s reaction against student social justice organizing.

As we study the housing crisis, we do a mixer activity, based on real people, from profiteers and policymakers to activists. Students learn about rigged systems, like how the biggest federal and state housing subsidy is the mortgage interest deduction, benefiting the richest households. Instead of individual shopping and budget choices, we look at how tenants organize unions and organize for policies like rent control (which mainstream economics teaches as a market- and prosperity-hindering price control, like minimum wages), public housing, public banks, eviction protections, and community land trusts. This contrasts with financial literacy programs like the My Classroom Economy curriculum sponsored by Vanguard and used in the Kent, Washington, school district, which has elementary school students paying rent for their desks and buying bathroom passes with classroom currency as a way of teaching discipline and financial responsibility.

It is also important to counter the deficit framing of financial literacy programs that blame the oppressed and exploited for their own suffering, rationalizing the ideology of meritocracy and capitalism. Research shows that poor people make more intelligent and informed choices than the rich, given the context they are forced into and that the “affluent are slightly more susceptible to misleading, comparative perceptions of price” (see Resource). The poor make economic decisions in a world of food and bank apartheid, wage theft, payday loans, etc., and given this, it’s difficult to make economic choices that lead to prosperity.

Despite the myths about self-made billionaires, inheritances and tax-evading trusts play an important role in their success. Promoting such financial success, a typical Junior Achievement curriculum goes step by step from lessons on career choices, budgeting, and savings to investing, passive income, and financial goals culminating in a calculation of individual net worth, with no attention to the outrageous levels of wealth inequality.

As youth face a crisis-prone world, we should teach them to understand it and organize to change it. The majority of jobs — now and projected — will be low-paid service jobs that don’t require a college education. In our current system, it’s impossible for all students to succeed economically. And they can’t individually make sound decisions about college debt when, for example, unfair practices by student loan servicing company Navient steered borrowers into forbearance resulting in increasing debt rather than income-based repayment plans. This is reminiscent of how banks steered borrowers of color into subprime loans. If students are to think intelligently about college debt, they ought to learn how states have cut education funding for years, including in my state, Oregon, where two out of three students eligible for aid have been denied.

Of course, education should be free and valued as a good in itself; all socially useful work should pay living wages; and all workers should be respected, just as everyone should have health care, pensions, and time and resources for leisure and enjoying life, culture, and nature. Instead, financial literacy curricula steer students away from learning about the broader social contexts that frame their personal decisions.

Educators should stop deceiving students — and ourselves — that every one of them can be “successful” in our capitalist society. However, we can teach them to understand the system and social movements that can change systems and create new ones and help them see that real changemakers are ordinary people like themselves. Rather than focus on individual choices in the market, we need to teach about power and social movements. And students should experience creative and collective problem-solving and how to organize direct action campaigns for social justice, as we’ve seen with Debt Collective and Strike Debt, part of a larger arc of social movements from the Arab Spring and Indignados to Occupy Wall Street in response to the 2008 global financial crisis — because “You Are Not a Loan.” As Paulo Freire argued in Pedagogy of the Oppressed:

Education either functions as an instrument which is used to facilitate integration of the younger generation into the logic of the present system and bring about conformity or it becomes the practice of freedom, the means by which [people] deal critically and creatively with reality and discover how to participate in the transformation of their world.

Resource

Max Ehrenfreund. “Why the poor do better on these simple tests of financial common sense.” The Washington Post. January 22, 2016. bit.ly/3oqvgO8