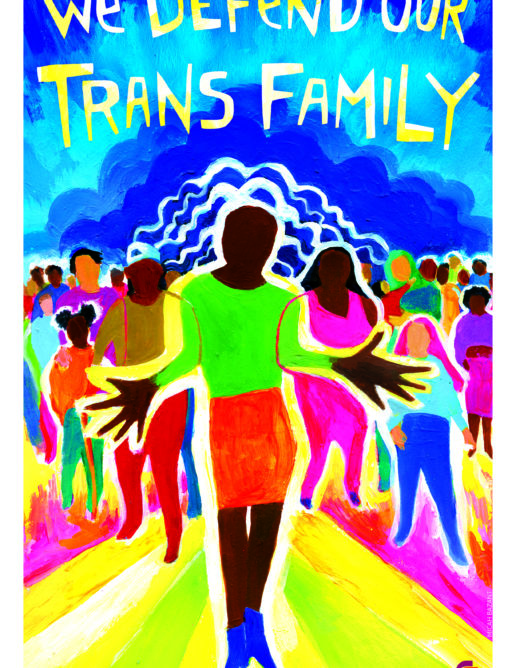

A high school English teacher (also the QSA staff advisor) wrestles with the suicide of a transgender student and calls on heterosexual and cisgender teachers to integrate LGBTQ authors, themes, and history into their classrooms.

A school librarian describes children’s books with strong transgender characters and themes.

What can teachers, schools, and districts do to meet the needs of trans students? To make them visible? To keep them alive? To celebrate them?

The staff advisor for their high school’s Queer-Straight Alliance delves into the complexities of a student-led training for teachers on the importance of using students’ preferred pronouns.

at the West tip of Texas

a line divides us from them

and on the other side

they all look like me

yet on my side we sit passively nearby

while the other side allows a slow genocide

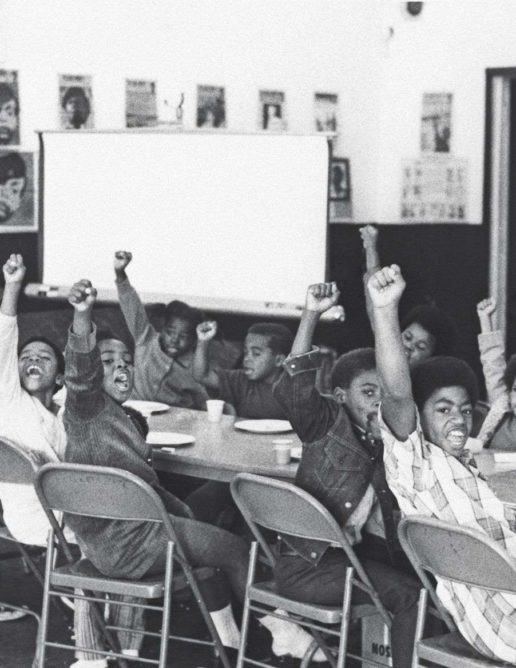

The history of the Black Panther Party holds vital lessons for today’s movement for Black lives and all movements to confront racism, inequality, and police violence. But our textbooks distort the significance of the Panthers — or exclude them completely.

A teacher in a predominantly white school and classroom describes how she chose to protect and educate one of her Black students, rather than use him to educate her white students.

I was just about to finish my second year teaching 2nd grade. It was the first week of June and school was quickly coming to a close. The sun was out and everyone’s energy was extraordinarily high. We were in Seattle after all; when the sun comes around, you rejoice. One morning that week I came to work and noticed I had an email from a parent. This was a parent I had a good relationship with, and she often checked in to see how her daughter was doing. But this email was different. The mother explained that her daughter had been cornered at recess the previous day by some boys who were also 2nd graders. The boys grabbed, groped, and humped her. They told her they were going to have sex with her. Her daughter told them to stop and to leave her alone, but they persisted. As this sweet one told her story of shame, confusion, and hurt to her family later that day, she became so upset that she threw up in the car. Her mother knew this wasn’t a miscommunication or misunderstanding.

To all of my students: I believe you.

Every Monday morning Lilly would walk into our 1st-grade classroom with downcast eyes and a heavy heart. She would wait for everyone to settle in and then quietly beckon me over to her seat and say, “My head hurts.”

It became a routine. I would stroke her head and say, “I know you miss your dad. Let’s try participating in school and see if it helps you feel better.” This seems like a reasonable response from a seasoned veteran teacher in her 31st year of teaching. My message to Lilly was I understand children, I understand your life, and I know what is best for you.

Since 1993, the Mexican border city of Ciudad Juárez has been shaken by disappearances of teenage girls and young women. Officials say they have few leads. The murders in Juárez have received some international attention, primarily due to government inaction. Yet little has been done by the government to prevent violence against women and girls, as officials neglect to bring their perpetrators to justice.

Residents do not let these deaths go unnoticed as hundreds of pink crosses — a symbol of these missing women — dot the border. An increase in these deaths coincided with the implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). A treaty between Mexico, the United States, and Canada, NAFTA sought to increase investment opportunities by eliminating tariffs and, like many other economic agreements, benefited the economic elites of the three countries while resulting in widespread unemployment, increased class stratification, and mass emigration. Most of the “disappeared” women work in assembly plants or maquiladoras, owned by the United States and transnational corporations that dashed to northern Mexico post-NAFTA to reap the benefits of lower wages and lax environmental regulation.

During a recent conversation, a former high school classmate said, “I always wondered why you left Eureka. I heard that something shameful happened, but I never knew what it was.”

Yes, something shameful happened. My former husband beat me in front of the Catholic Church in downtown Eureka. He tore hunks of hair from my scalp, broke my nose, and battered my body. It wasn’t the first time during the nine months of our marriage. When he fell into a drunken sleep, I found the keys he used to keep me locked inside and I fled, wearing a bikini and a bloodied white fisherman’s sweater. For those nine months I had lived in fear of his hands, of drives into the country where he might kill me and bury my body. I lived in fear that if I fled, he might harm my mother or my sister.

I carried that fear and shame around for years. Because even though I left the marriage and the abuse, people said things like “I’d never let some man beat me.” There was no way to tell them the whole story: How growing up and “getting a man” was the goal, how making a marriage work was my responsibility, how failure was a stigma I couldn’t bear.

Recently, a Rethinking Schools editor was a chaperone on a field trip when he overheard a 2nd-grade student talking about how he wanted to “nuke the world.” Taken aback, he […]

A teacher wrestles with explaining refugee crises, dictators, and the trauma of war to her 1st- and 2nd- grade classroom.

A teacher adapts the “Climate Change Mixer” designed for older students as a springboard for a unit on global warming and climate justice.

A science teacher includes Black voices and Black history in her classroom by building curriculum around The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. In doing so, she shows how nonfiction books should not be relegated to language arts but can be effective in a science classroom.

A kindergarten teacher uses images, literature, poetry, and collages — as well as her own history — to challenge students’ implicit bias and preconceived notions surrounding the color black and to teach the lesson that Black is beautiful.

As we return to our schools this fall, we need to rededicate ourselves to building an education system and a society that values Black lives.

Teachers at one Seattle school show the important role educators have to play in the movement for Black lives, in part by creating a Black Lives Matter at School day, having 3,000 teachers wear Black Lives Matter T-shirts, and responding together to issues like the death of Charleena Lyles.

Una maestra de primaria se da cuenta que debe dejar a un lado el guión y la antología de su currículo para encontrar literatura latina en español y abrir un espacio a las vidas de sus estudiantes.

Los estudiantes de segundo grado escriben junto con sus familias, desafiando las políticas monolingües, anti-inmigrantes, y de segregación de Arizona.

Second graders and their families write together, countering Arizona’s English-only, segregated, and anti-immigrant school policies.

Una maestra de noveno grado explica cómo desarrollar un currículo de educación sexual que sea positivo e inclusivo.

A 9th-grade teacher lays groundwork for sex education that is sex-positive and inclusive.

Una directora escolar describe el proceso que transcurrió su escuela primaria al darle la bienvenida a una nueva estudiante transgénero de octavo grado y a otro estudiante que estaba haciendo una transición de género.

An administrator describes the journey of her K-8 school as it welcomes a transgender 8th grader and the gender transition of another student.