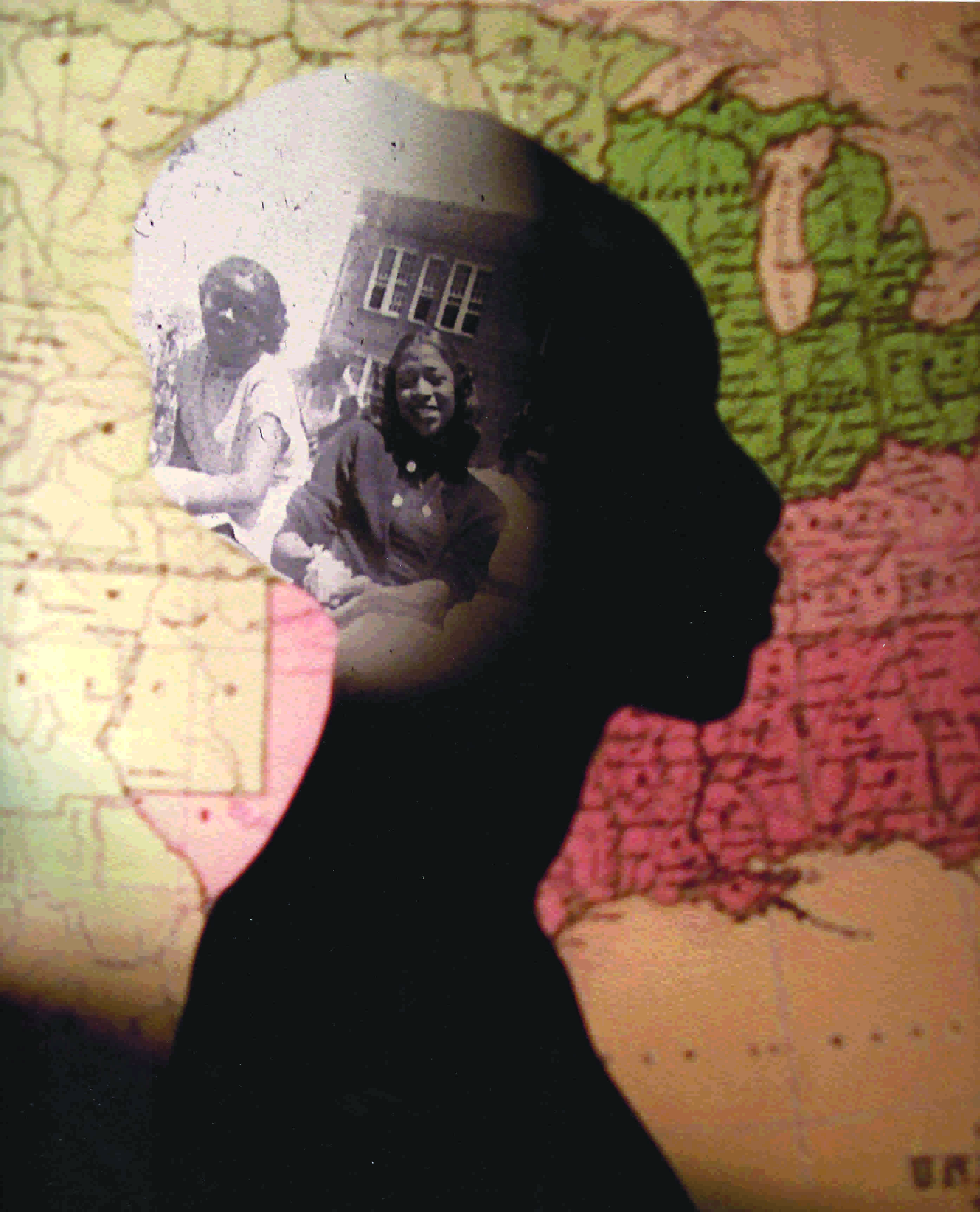

Black is Beautiful

Illustrator: Kesha Bruce

For years, I have struggled to find authentic ways of helping young children — kindergarteners and 1st graders — learn, remember, and appreciate Black history. Come January, the halls of my school are plastered with a variety of Martin Luther King Jr. tributes and artwork that conveniently find their way to being relabeled for February’s Black History Month displays — and disappear in time for March’s green living tips to save the planet.

But here is what my students need to know: Black is beautiful.

And here is why they need to know it…

Currently, in my predominantly white kindergarten class of 27, I see the few Black boys in my class targeted as the ones who did something wrong, as the kids who are called mean, as the kids who are not named as a friend. I see my one Black girl sad on the playground, or looking for a spot at the table with her white peers, unsure how to make space for herself. They are on the periphery of play, usually the “it” in tag, and it reminds me of my own story: In high school a teacher told us that, in our society, the color black symbolizes bad and evil, and white symbolizes good and pure.

I also remember when I was in a human development college class watching a video clip of children choosing a white baby doll instead of a brown one. I remember a little Black girl in the study saying the brown dolls were not as pretty, and the little white girls saying the brown dolls looked dirty. The video and the study itself made me sad for the little Brown girl I once was, trying to fit in and make friends in school.

One day I came across a stack of books the former librarian volunteer at my elementary school was going to throw out marked “Free books.” In it were two copies of Black Is Beautiful. It was published in the ’70s by Ann McGovern and made up of black-and-white photos of simple black subjects: a black bird, black jelly beans, black puppies, a black butterfly, a young Black girl in dress-up. The words in the book were written like a free verse poem. I loved the simplicity and took both copies to use in my classroom.

The students listened to me read aloud using a voice of wonderment and adoration — some pages I whispered in reverence. I stopped at the page of the Black girl playing dress-up in her mom’s clothes, the only page mentioning black skin being beautiful:

Black lace, black face.

Black is beautiful.

“Do you see her wearing her mama’s fancy clothes? So beautiful and fun,” I said. When I finished, I asked what they noticed in the book.

“I notice the pictures only had black.”

“I notice a black bird.”

“I noticed beautiful.”

“The horse was black!”

“I noticed the candy!”

“Yeah!” the class responds in a chorus of agreement.

I wrote down what they noticed on chart paper. Then I asked, “What can we add to this Black Is Beautiful book that the author didn’t mention?”

“The tire swing!” Timothy said.

“Some people may not see a tire swing as beautiful. How can we convince them it is? I think about how some of you love to push it, and some of you love to ride on the tire swing. Hmm . . . what would some beautiful movement words be that you could say with tire swing?”

“It twirls!”

“It spins around and around!” said Chris, who was now on his knees, having popped up during his share out.

“Oooh! I can’t wait to see how you write that!” I popped up too, and smiled.

I moved on, asking for more ideas. I framed their answers in the style and context of the book we read, modeling how to expand their list to sound like a poem. I wrote down their new ideas, and pointed to the ones already mentioned or from the original text: a kitten, a dog, sneakers, a witch.

“I notice the author wrote this like poetry to help us remember how beautiful the things in the book were. What words and descriptions can we add to our ideas to make people see the beauty and goodness of the color black?”

“My dress is soft and cozy,” Lori gently patted her black fuzzy skirt, smiling into her own shoulder.

Nadira, who had been gazing away, raised her hand. “Black bird floating in the night sky.”

I wrote what they said on the board and asked them to tell a friend three black things they are going to write about in a beautiful way. I know some will only get a picture or a word down while some will fill the page, but I want them all to start by telling someone three things. It gives them a goal and sets the expectation with a starting point.

I sent them off to write their ideas and have “Black is beautiful” written on sentence strips at each writing table for reference. I collected their work, went home, and typed them up.

The next day we reviewed: “Who remembers something that is black and beautiful?”

“Horses!”

“Birds!”

“Sneakers!”

“Rain clouds!”

“Yes!” I said. “Today we are going to look at a different kind of black is beautiful. We know that there are things that are black and beautiful, and people who are Black and beautiful. But it can be a little confusing because is people’s skin the color of black paper or a black shirt? No! Black people are all different shades of brown. We just call it black sometimes. Today we are going to write about beautiful Black people and I have a few books to share with you to help give you ideas.”

I started off by reading My People by Langston Hughes.

“Sunshines, I love this book,” I told my students. “The words in this book are so simple and so powerful. This book is actually a short poem that was stretched across the pages so the photographs could illustrate each line of the poem. When I read this poem to you, I want you to study the pictures as you hear the words I say. Look at the faces and features of these Black people and notice their beauty. Notice what Langston compares the beauty to. In one place he compares me to the sun! I always feel so great when I read this poem.”

The night is beautiful,

So the faces of my people.The stars are beautiful,

So the eyes of my people.Beautiful, also, is the sun.

Beautiful, also, are the souls

of my people.

I tell them to listen to ways Langston knows Black- and Brown-skinned people are beautiful. It’s a slow book, with only a few words per page, which allows my students to study the sepia-toned photos. Using the same format from the last lesson, we try to translate the idea of black is beautiful to features of Black and Brown people. After I finished the book, I ask the students to tell me about beautiful Black people. “What did Langston say?”

“Beautiful like the sun.”

“The stars are beautiful!”

I am explicit when I talk to the students about the metaphor in this poem. It is hard to understand when you are 5 years old and the world is a literal, concrete place. Some do not make the connections I want them to make, they are not thinking about the Black people of the poem but of their metaphors as the thing of beauty. So I make the connection for them and carry them with me through an example.

“Now you understand why I love this poem. Langston compares beautiful people with the sun and stars. Look at this page.” I show them the page of an elderly man, face raised and smiling at something unseen to the reader. “When I look at this page, I see joy and happiness. I see lines around his mouth that say he smiles a lot. His skin looks soft to touch. That is why he looks beautiful to me, and I think that’s why they chose this picture to go with the word ‘also’ in the poem. Sometimes we think of beauty one way and then discover, like in this book, there are other ways that we can see beauty!”

I re-read the poem and asked for “Black is beautiful” examples again. This time there are more accurate answers:

“Eyes are beautiful!”

“Brown skin is beautiful.”

“Hands are beautiful.”

Brandon, a Black boy who often sits quietly as if in meditation, raised his hand. “Souls are beautiful.” He looks at me and we smile.

We also read Hair Dance! by Dinah Johnson, another book with photos of Black and Brown kids playing outside. There is so much visual movement in this book; kids are jumping and hair is swinging. This book is special because the children in the book are from our neighborhood, the author is a parent, the kids were previous students in our school. This interests the children and they study the pictures and recognize some of their playground in the artwork. This time around when kids answer what is beautiful, they move their heads as if flipping their own imaginary beaded braids. They are holding their own hair in the air to mimic the pictures they saw while I read the rhythmic words in the book. The resounding agreement is that Black hair is beautiful — and so is jumping! We spend two minutes trying to jump high and fast to get our own hair to dance.

But this time when I sent them to write, they were less confident. Maybe I moved too quickly, or maybe the metaphor was too big of a jump. They stuck pretty close to the examples given in the books: hands, hair, skin. They focused on the metaphor and less on the physical attributes of people as beautiful.

And this was what my students deserve to know: Black is beautiful.

I tell the kids why I think it’s important to celebrate Black history. I tell them my story, of learning about history where no one looked like me or my family. “We have Black History Month as a reminder to teachers that there is not much written about all of the things that Black and Brown people have contributed to our lives. When I was a kid, I only learned about the ways white people changed our lives. There were no books or activities in our school that let us know who those Black people were, or how they affected the way we live. I will share inventors and leaders who paved the way, or made an important discovery through diligence and hard work.” They seemed intrigued. Some looked surprised, some totally bored. Buy-in to the unknown is hard, so I gave them an example.

Fresh off the heels of a presidential election with an unexpected outcome, where girls were coming in wearing pussycat hats and pant suits, I told the class about Shirley Chisholm.

I then told them mostly about inventors or “real firsts,” as opposed to firsts for Black people, because they are the most tangible for young learners to understand. It is a clear, concrete contribution to bettering our daily lives: refrigeration, open-heart surgery, stoplights, peanut butter. I want my students to have a basis for appreciating Black people. Later, when they learn about the more complex concepts of slavery, Jim Crow, and civil rights, somewhere in the back of their mind I hope they will remember the beauty of Black and the ways Black people made life better for them. And then maybe, in the front of their eyes, they will see the injustice for what it was and what it still is.

For the next writing exercise, to retain the feeling of reverence we stayed with the free verse poetry writing style of the first book I introduced by Langston Hughes. The tone of that piece set the mood for the beauty on the page, and allowed them to transition into that poetic mode of writing, thinking, and seeing their ideas in a different light. I had them talk in pairs and instructed them to tell each other who they remember learning about and liked. When I asked them to write, they quickly jotted down their choices: Stoplights speak to cars in colors, tasty peanut butter on sandwiches for lunch every day, open-heart surgery saving lives.

When writing with young children, I have to make publishing decisions. In this unit, I wanted the kids to see their ideas from these lessons typed up and put together as a collective piece. If I made them do the extra combining work it could make the unit drag on too long, its message losing potency. So, in this instance, I did it for them.

Once all the parts were typed into one poem, I brought in craft and scrapbook supplies all in black: pipe cleaners, pom-poms, feathers, beads, stickers, textured felt, and dozens of patterned papers; all glittery, soft, and shiny — the jewels of the crafting world. I cropped their poems and let them collage them into beautiful black works of art. I read the poems aloud as I handed them out one at a time, so they could hear each other’s work as inspiration.

Resistance

Some years when I do this lesson, I get backlash in the form of parent emails to the principal, disengagement from students, or the fairness argument from both students and parents: “Why just black, why not all colors?” This year it was Andrew, a tall blue-eyed white boy, and a proficient reader and writer.

When he learned about Black inventor Lyda Newman’s improved hairbrush, Andrew whispered to a friend, “That’s not special.”

When he saw the sentence strips with “Black is beautiful” written on them for a second day, he turned them face down on the tables and exclaimed, “We already did these!”

When Jasmin told her friends something Black was beautiful, he responded, “Black is not beautiful.”

Andrew, whose humor sometimes runs in the center of insulting, who often finds delight in others’ misfortune, exclusion, or embarrassment, was creating another opportunity for me to change his mind.

When he turned the sentence strips face down exclaiming their completion, I explained this project was going to last the entire month. “Sometimes we remember things better and learn more when we stick with it. It feels like we finished because we did finish one part, but there’s more I want to show you and more I want you to try.” Andrew said, “OK.”

When he said Ms. Newman’s invention wasn’t special, I noted there is a difference between flashy and noteworthy. “Raise your hand if you have a brush like this one in your house. Raise your hand if you’ve seen one before. Isn’t that cool you’re learning about the person who made something we’ve all seen or used every day? That’s why I wanted you to learn about Ms. Newman. She gave us things we use so much they seem boring, but every time someone uses or buys it, she is getting affirmation that what she created was needed, even still today!” I make eye contact with Andrew when I say this, and he nods in agreement.

When Jasmin came to me upset that Andrew told her Black wasn’t beautiful, I took him aside and told him about the power of an ally.

“Why did you say Black isn’t beautiful to Jasmin?”

“I was kidding. It is.” He tries to get the early exit card by placating me.

“I’m spending a lot of time on Black is beautiful because I want you on my team, Andrew. I want you to be the person who stands up and defends Black when someone else tries to do what you just did, tries to make a joke about it, and tries to hurt someone’s feelings about Black. Black isn’t just a color of clothes, right?”

“No, it’s people and brown skin.”

“So when someone jokes about Black, it makes us, people with that skin, feel less important. But you have a chance to be a leader. Friends look to you to include them and they follow your lead. If you decide not to treat Black as a joke, if you tell a friend why it’s not funny to joke like that, you’ll be helping the unfairness that is all around us. You will be making this place a better place for more of us. Can you try to do that? Help us feel welcomed and proud of Black?”

Andrew nods, “OK, yeah! I’m sorry I hurt Jasmin’s feelings, Ms. Kara.”

“I know, Andrew. Thank you for apologizing. I’m glad you’re on my team.” Andrew smiles shyly and takes a big breath.

Then I take a big breath as he goes back to his seat.

Yeah, the work is weighty, little one. Deep breaths help.