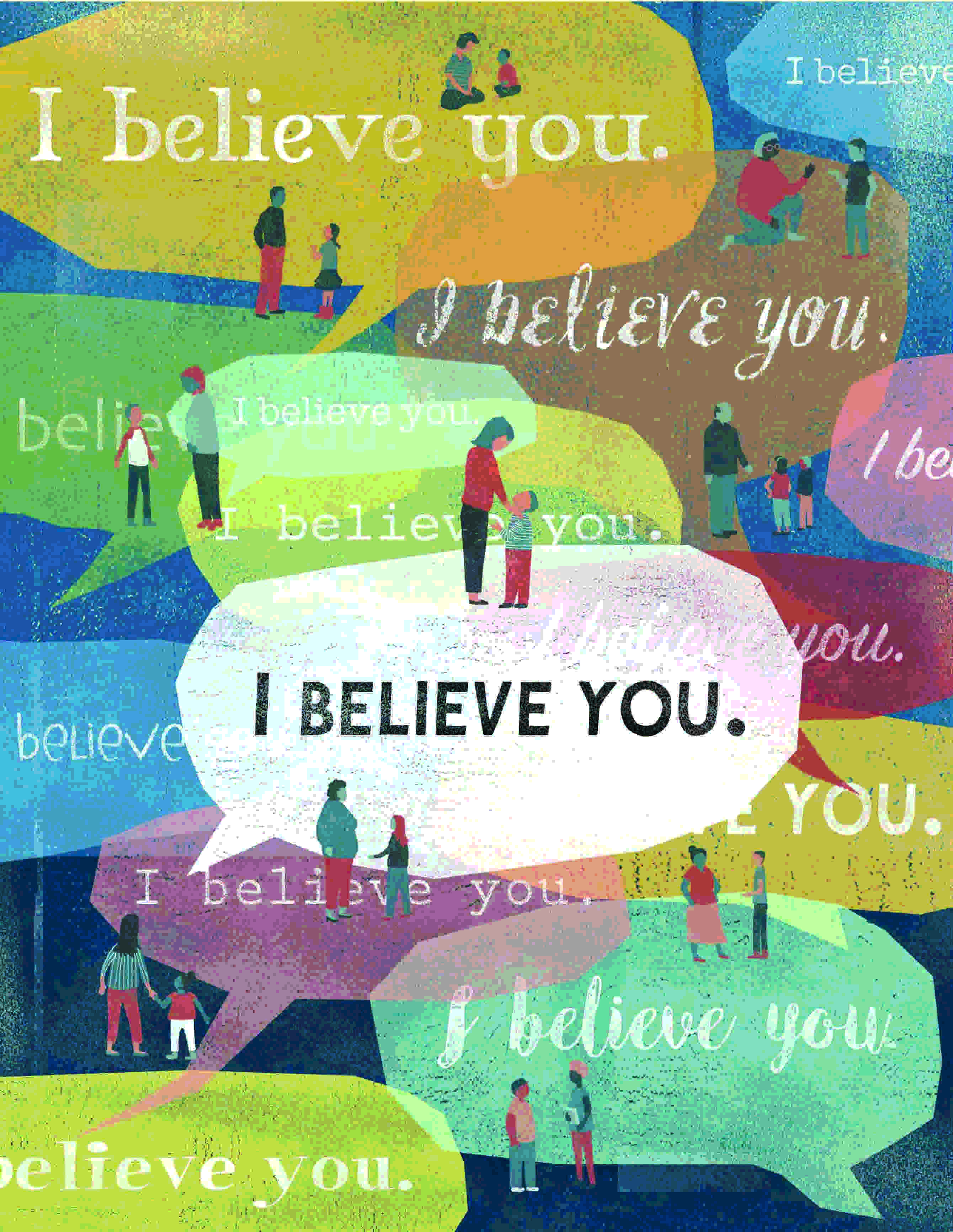

“I Believe You”

Responsive Teacher Talk and Our Children’s Lives

Illustrator: Simone Shin

To all of my students: I believe you.

Every Monday morning Lilly would walk into our 1st-grade classroom with downcast eyes and a heavy heart. She would wait for everyone to settle in and then quietly beckon me over to her seat and say, “My head hurts.”

It became a routine. I would stroke her head and say, “I know you miss your dad. Let’s try participating in school and see if it helps you feel better.” This seems like a reasonable response from a seasoned veteran teacher in her 31st year of teaching. My message to Lilly was I understand children, I understand your life, and I know what is best for you.

I had Lilly in mind this past January when Olympic gymnastics physician Larry Nassar was sentenced to 175 years for multiple sex crimes perpetrated on some of our nation’s most vulnerable young people. While watching the news and listening to some of their testimony during the sentencing hearing, I kept saying to myself over and over again, “I believe you.”

Thinking of Lilly and her Monday morning headaches, I realized that I was discounting Lilly’s experience and not fully listening to her. It was then that I recognized that I needed to change my response when children report to me — headaches, scraped knees, someone hurting their feelings — by saying “I believe you” before responding to the incident. Although Lilly was not reporting serious assault or abuse, as in the case of the gymnasts, I have come to believe that fostering a culture of belief in children and their words is a step toward giving them the tools to advocate for themselves in all aspects of their lives.

I teach an inclusion classroom, a blend of both general and special education, in a neighborhood school in Chicago. There are five adults who work together serving 27 children, nine of whom have special needs. The adult roles in our classroom include myself as the general education teacher, a special education teacher, two classroom assistants assigned to individual children, and a student teacher. There are many moving parts in our classroom and luckily the adults take time to talk and plan together. For the most part, all of us are on the same page when it comes to teaching children. We are justice-minded and strive to keep developmentally appropriate practice in our classroom.

That week of the Dr. Nassar news reports, I approached our team with the idea of deciding to respond with the “I believe you” sentence stem to children reporting incidents or concerns to us. We talked about the need to validate children’s experiences and feelings. We debated whether or not to say, “I hear you.” But in the end we concluded that telling a child you believe them gets to the truth we hoped to impart. My student teacher, Emily Lanz, said, “You can always tell someone you hear them, but believing someone is a whole different story. It is the investment in the truth of the child’s life.”

After several days of practicing “I believe you” as our response to children, we took time in our team meeting for reflections. Todd Reynolds, the special education certified aide in our room, is queer. He often tells us of how hard it was to grow up in Springfield, Missouri, and that he was often misunderstood by his teachers and peers. During our discussion he said, “I can’t imagine how much different my life would have been if someone had said ‘I believe you’ instead of ‘You’ll grow out of it.'”

Rolling Out “I Believe You” in Our Classroom

We spent the next three weeks putting this practice into our teaching routines. As a team we would note the occasions when we used “I believe you” with children, and we would discuss its effectiveness. All of us experienced a shift in our classroom climate and our relationships with the children. Emily Lanz, our student teacher, said, “Our room just feels gentler now.”

At one point during this three-week trial period, a child came to me and said, “David hit me.” I responded, “I believe you; let’s go talk to him to see what he has to say.” If the incident reported by a child involves someone else, we always give the other child a chance to respond. “I believe you” doesn’t mean that we think the child is telling the whole truth, but it is the truth from their perspective. The next step is helping the child see the other person’s truth.

Here are some more examples of our work that give a picture of this shift in practice.

One student said, “Mr. Reynolds, my brother gets all of the attention at home.” Mr. Reynolds responded, “I believe you. Let’s find ways to celebrate you at school.”

Jonah said to me on Valentine’s Day “Mrs. Gunderson, I just love Debby. My heart is bursting.” My reply included coaching, “I believe you. Debby is wonderful. Let’s talk about what it means to love someone in 1st grade, and what it looks like.”

And because we teach 1st grade, some of the reports include the typical squabbles of 6-year-olds. As we were walking out the door on Friday, a little one came up to me and said, “Jeff pretended to fart on me.” “I believe you,” I said. “Let’s go talk to Jeff about how to treat friends.”

One of the dilemmas I confront as a teacher of young children is how to respond to a child’s report when I think they are not telling the truth or exaggerating. I was listening to two children happily playing in the block center when the blocks came crashing down. Zora ran to me and said, “Tommie always knocks down my buildings.” I said to her, “I believe you about being upset about your building. Let’s talk about what the word ‘always’ means.”

One of the complications we experienced was dealing with tattling, a normal part of teaching 1st grade. Children at this age become reporters of every transgression, and it is important that educators help children learn to independently work on their own problems. In our classroom we define “tattles” as saying something just to get someone in trouble and “tells” as reporting something a child needs adult help with or something an adult should know. It is an imperfect system, and takes a long time for children to process the difference between the two.

When reflecting on our new process, Todd Reynolds said, “Some of these examples are ‘tattles’ and others are ‘tells,’ but by saying, ‘I believe you’ you let the child know that no matter the outcome, their concerns were not dismissed when they came forward. I think it is not about a new way to handle conflict resolution — we will still use the opportunity to help the child distinguish between a ‘tattle’ and a ‘tell’ and each will be dealt with appropriately — but, ‘I believe you,’ sends a strong message to children that the adults in their lives are present and take their safety and concerns seriously.”

Making Our Practice Public with Our Students

After three weeks of practicing and analyzing our “I believe you” focus, we were ready to talk to the students about it. Our kids love it when we gather them on the rug to have a serious life talk. They quietly sat down in our gathering space and looked at me with the seriousness that always settles over our special talks.

I told the children how much we care that they experience school as a safe and caring place. Then all of the teachers explained that we have been very intentional in using “I believe you” when they come and talk to us. We gave the children our examples and our explanation about our decision. I talked about an incident that happened the day before when Elsie told me that someone had taken her place at the lunch table and that it hurt her feelings. Elsie remembered that I had said, “I believe you. Let’s go see how that happened” while taking her by the hand to talk to the group of girls.

We then read the book Mae Among the Stars by Roda Ahmed. This is an illustrated biography of Mae Jemison, the first African American female astronaut. Of special interest to my students, Dr. Jemison was a student at Morgan Park High School on Chicago’s South Side. In this picture book, Mae Jemison explains to her parents her dream of becoming an astronaut. They take Mae to the library and buy her a telescope. She is determined to “see Earth from out there.” But on Career Day, when Mae told her teacher that she wanted to be an astronaut, her teacher said, “Mae, are you sure you don’t want to be a nurse? Nursing would be a good profession for someone like you.” The subtext of this encounter being, that as a Black female this would be the obvious profession open to her.

After we read the book I asked our students to write what they were thinking about how the teacher treated Mae.

One student wrote, “What I was thinking is that it was mean to treat Mae like that. She should chase her dream not the teacher’s.”

Another child said, “If I was going to have a new teacher, I would want to be told ‘I can.'”

“I was thinking the teacher did not treat Mae how a teacher should. Like she didn’t care deeply about Mae.”

Our students are very young, yet they understand the subtlety and subtext of adult and child interactions. We noticed that the children’s writings were not as rich and developed as the whole group classroom discussion we had. For example, John said during the discussion, “In the story, the teacher put Mae in a box,” which is a very colorful description of the story event. In his writing, however, he said, “I was mad.” This is to be expected.

Many times 1st-grade students can verbally explain complex thoughts, yet their writing does not capture it all. This is one of the reasons we allow children to talk issues through, draw, and write in our classroom. Multiple responses are important in order to engage children on different levels. All of their responses reaffirmed to our team that we were on the right track. After reading through the children’s work, our student teacher said, “Imagine if our students insisted on being spoken to fairly throughout their lives.”

Students are now recognizing “I believe you” moments on their own. The other day we read Amazing Grace by Mary Hoffman in order to develop a character study, totally aside from explicit teaching of “I believe you.” In this book, Grace is told by her classmates that she cannot be Peter Pan in the play because she is Black and a girl. Grace eventually takes on the persona of Peter Pan and astounds her classmates at the audition. At the end of the reading, Elsie said, “That was an ‘I believe you story.'” We all agreed.

This is how we embarked on our journey together with our students, letting them know that our words and actions are intentional, and that we care deeply about them. After our Mae Jemison lesson our team discussed our hopes for our students. We concluded that our hope is that we are building a pathway to empowerment for them.

Many of the people I have spoken to about this have told me instances where an adult saying “I believe you” would have changed their lives. Imagine the difference across race, across class, across gender if we would say “I believe you” to one another instead of “really?” or “well, actually . . .” It is no small thing we do when we structure our classrooms around respect and empowerment — our words can make all the difference in the world.

Michelle Strater Gunderson is a 31-year teaching veteran who teaches 1st grade in the Chicago Public Schools. She is the chair of the Early Childhood Committee for the Chicago Teachers Union, where she also serves on the board of trustees.

Illustrator Simone Shin’s work can be found at simoneshin.com.