“How Could You Let This Happen?”

Dealing with 2nd Graders and Rape Culture

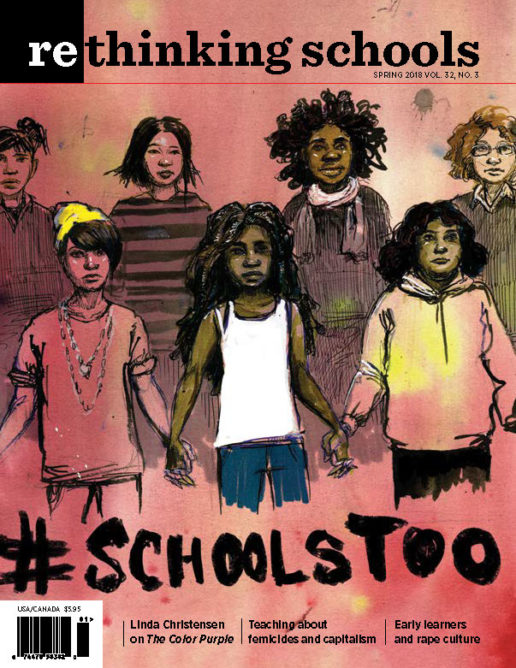

Illustrator: Olivia Wise

I was just about to finish my second year teaching 2nd grade. It was the first week of June and school was quickly coming to a close. The sun was out and everyone’s energy was extraordinarily high. We were in Seattle after all; when the sun comes around, you rejoice. One morning that week I came to work and noticed I had an email from a parent. This was a parent I had a good relationship with, and she often checked in to see how her daughter was doing. But this email was different. The mother explained that her daughter had been cornered at recess the previous day by some boys who were also 2nd graders. The boys grabbed, groped, and humped her. They told her they were going to have sex with her. Her daughter told them to stop and to leave her alone, but they persisted. As this sweet one told her story of shame, confusion, and hurt to her family later that day, she became so upset that she threw up in the car. Her mother knew this wasn’t a miscommunication or misunderstanding. She believed her daughter.

I could feel the anger as I continued to read the mother’s message. Why wasn’t someone watching these students? Where were the recess monitors? I just don’t understand how students could be doing this and no one saw anything. What are you going to do about it? And how could you let this happen? I could also feel the hurt and distrust this mother was feeling. Not only in me, but also in our school system for letting her daughter down. I then imagined the fear this 8-year-old student could be experiencing right now as she got ready for school. Fear of her male peers. Fear of the institution that has let her down in more ways than one. Fear that her body and her rights to her body can, and most likely will, be taken without her consent.

As a queer, Black woman, I could understand what this student might be feeling. I have felt that fear before. I have been afraid of males, both peers and strangers. I have felt the anger toward a system that has failed me and continues to fail others.

I did what many of us are told to do in our teacher preparation programs. I went to the person designated to help guide us through these sticky situations; I knocked on my principal’s office door. I told him about the message and asked for his insight and support. I watched him lean back in his chair to the point of a half slouch. He looked up at me with tired, irritated eyes.

“Whose class are the boys in?”

I responded with their teacher’s name.

“And whose class is the girl in?”

“Mine,” I said, annoyed he didn’t listen at the beginning when I gave this information.

He began to speak like he was checking boxes off of a list of things I should have already done myself.

“Well, where were the recess monitors? Did she tell one of them yesterday?”

“I’m not sure; the family didn’t say if she told anyone at school. Just the parents so far. And now myself.”

His shoulders dropped as he let out a sigh.

“Well, talk with your 2nd-grade colleague and decide how many recesses the boys should miss. Then email the alternative recess teacher and let her know how many days they will be coming.”

He went back to whatever work was pulling him away from the conversation. I stood a moment, shocked by his lack of response. I was perplexed that in six minutes, we had “solved” this problem. I reluctantly thanked him for his time and walked out of his office. As I walked down the hallway to my classroom, each step filling my body with anger, I replayed the conversation in my head.

Take away recess? That’s it? Recess? Was he even fucking listening to me? And what do you think will happen when they go back to recess, huh? Why are we punishing, not educating? Taking away something they desire and benefit from isn’t effectively teaching them to respect the rights that individuals have to their bodies. This does not feel right.

In the end, I did what I was told and collaborated with the other 2nd-grade teachers. Much to my relief, the other teachers were also angered by our administrator’s response. We shared the feeling of knowing something was wrong and that we should be doing something about it, but not having enough knowledge or resources to know what should or could be done. We agreed that in the next few days we would all have conversations with our students about personal space and respect for others. We understood that this would not solve the problem or even begin to scratch the surface, but it was better than pretending it never happened.

It is important to note that my district uses the FLASH curriculum. FLASH is a comprehensive sexual health education curriculum created by the King County Public Health Department. It includes puberty, abstinence, birth control methods, consent, and reporting harassment. However, as in many schools around the United States, you do not receive sexual health education professional development, curriculum, or support unless you teach 4th grade or above. Apparently, in our society, if you are not in the midst of puberty, there is no reason for you to learn about sexual health.

I chose to discuss personal space with my students during our class meeting the following day. I began with our usual greeting and then dove right in.

“Friends, today I want to talk about something so very important. I want to talk to you about something called personal space. Personal space is this idea that everyone has their own bubble around them.” I stretched my arms out in front, behind, and to all sides of me emphasizing the space around me.

I had my students stretch their arms around them and see their personal space.

“Sometimes people or things come into our personal space. How do you think you would feel if someone came into your personal space without asking you?”

“Squished!”

“Annoyed!”

“Mad.”

“Yes! Sometimes when people or things come into our personal space without asking, it can make us feel bad. Opposite of that, sometimes people or things come into our personal space because we ask them to or we want them to. It can be good if we want to feel cozy or cared for with a hug. But sometimes bad when it makes us feel uncomfortable, squished, or even unsafe. Everyone is able to decide who or what gets into our personal space. We have the right to say yes or no. And it’s important you know that, because sometimes people will get into our personal space without asking and it’s OK to say no to that or tell someone to stop. Does this make sense?”

One of my students raised their hand and asked a question.

“But I should tell them in a kind way, right? Use my kind respectful voice?”

“Yes, friend! You are so right. It’s during those times we feel uncomfortable or unsafe that our strong, respectful voice is so important. Say something like you mean it and say it proud.” I made sure to include the word

“strong” because I want my students to know that they need to be strong when advocating for themselves.

Conveying to them that their voice is strong from an early age is important because it begins to foster the belief that what they say should matter, even if the person receiving it doesn’t listen.

I knew the message I was trying to convey to students would not be understood in one small conversation during the last two weeks of school. Looking back, I’m still unsure about how to best address the complex issues of sexual assault and consent with 8-year-olds. However, I do know what I want them to come away understanding. I want to teach my students to love and accept the bodies of all people, including their own. I want them to understand consent, and that they have the right to say no. I want them to believe that their body is theirs and not at the mercy of others. I also want the boys who have engaged in these aggressive behaviors toward their female peers to be able to heal from whatever traumas and hurt in their lives have led them to believe that they can take ownership of other people’s bodies.

As a second-year teacher, I struggled to find the best way to teach my students these things. I wish that there had been time and administrative support for us teachers to meet, talk through these issues, and develop curriculum around them. Working together, we could have leveraged the knowledge of more experienced teachers and brought in outside experts. This problem was not isolated to my classroom, or even to the 2nd grade — it was a schoolwide issue and deserved a schoolwide response. But I didn’t know how to advocate for that, and I knew by doing and saying nothing, I would be continuing this cycle of violation, shame, and distrust for these tiny humans. Teaching about personal space during a class meeting was at least a concrete first step that I could take immediately.

I also responded to the family to let them know I heard their concerns and was doing everything I could to help reach a resolution. I told the family that I had gone to the principal to discuss the issue. I also decided to be honest about my principal’s response. The family was kind and thanked me. They assured me they would also go to the principal and see if that helped. I explained that in my experience, parents’ opinions and views could weigh heavily on the administration, sometimes more than the views of teachers.

A few days went by. The boys completed their consequence and were allowed to return to recess. Our principal had pulled the boys during the course of their consequence to “speak” with them. He told us that he asked the boys if they did what they were accused of and they denied it. He also asked them if they understood what that type of touch meant and they all said no. This led him to believe the situation wasn’t as real as everyone was making it seem.

Once the boys were allowed back at recess, the touching resurfaced — just as I had suspected it would. However, the boys now targeted a few more girls. I received more emails and phone calls from families with the same question: How could you let this happen?

I felt I had let these students down. I couldn’t protect the ones who needed it most. And I didn’t know how to speak to the ones creating these issues. I mustered the strength to talk to my administrator again. And again, I was disappointed. This time, my principal told me, “Younger students don’t really understand their actions or what they are doing. They really don’t know what sex is, or inappropriate touch.” He went on to tell me that “Sometimes parents hold onto things that happen to their children and hold a grudge when their children are fine and not bothered at all.” My administrator felt that since the girls weren’t distraught at school, or telling us at school directly, they must be fine.

We often dismiss children’s ability to understand complex topics. Yet they possess such wonderful ability to understand and process the things we may feel are beyond their reach. Yes, there are things that are developmentally inappropriate to bring up with 2nd graders, but 7- and 8-year-olds can understand and discuss the concept of violating the space, property, or body of others.

I was floored by my administration’s response the second time around. I was floored that the leader of my school was telling me that this simply wasn’t an issue — that the fear my students were feeling wasn’t real. I couldn’t understand why we were treating this like a childish dispute over who would go first in Monopoly.

My principal’s choices perpetuated rape culture, a culture so deeply ingrained in our society that none of us knows a time when women’s bodies weren’t at the expense of men.

My heart was telling me how wrong it was to act like nothing had happened. Parents were looking to me for answers, angry that I had let them down. But my head was telling me to use caution. This was my administrator I was talking to. This was my boss. I feared continuing to question my administrator’s authority. Would this affect my evaluation? Would he try to push me out? Would he make my life here a living hell? As I reflect back on this time in my career, I wish I had reached out to my union president. I was a new building representative for my school during this time, but still feared the power that principals possess over teachers. I think my union would have supported me and helped me walk through the fire.

I questioned more. If I don’t say something, who will? If I don’t show my girls they have the right to their own body, who will? And then I realized none of my fears mattered in comparison to the heartache my students were going through and would go through.

The next day I went to my colleague, the teacher of the boys involved, and told her about my second encounter with our principal. I told her that I felt lost and scared, and that I thought I was letting my students down but didn’t know what else to do. After a few tears and hugs, we decided to do this together. We wanted to be honest with our principal and try to get him to understand that this was serious.

That day we spent our planning period crafting an email. In that email we told our administrator that his lack of response showed our students that their bodies didn’t matter. That we didn’t care enough to protect them or educate them, even when they asked us to. We told him we felt strongly that this silence perpetuated rape culture, and that staying silent allowed these societal beliefs to affect our students at younger and younger ages. We know it’s hard to understand that these types of behaviors can be happening in 2nd grade, but they are. We asked him to take our parents and students seriously, and to support us in working through these issues.

Unfortunately, the only line from the email that stood out to him was “rape culture.” He was defensive and said that we were mislabeling the situation. He asked to speak with each of us privately to discuss the matter further. We were now in trouble.

By the time I was able to schedule my meeting with my administrator, it was the last week of school. I felt defeated. How much problem-solving could we get done in five days? We had already wasted so much time doing nothing. I would be lying if I didn’t admit that I was also scared as hell. My principal was calling for a private meeting! Had we gone too far with the email? Was I now not just the loud Black teacher, but also the loud, angry, undermining Black teacher? Could he fire me four days before school was out?

Right before my meeting, a few colleagues stopped by my room to tell me they had heard about what was going on and wanted to let me know they supported what I was doing. They told me to stand strong and fight for my students. I’m grateful for those few people who came into my room. It gave me the strength to stand my ground. Yet I wish some of them had accompanied me to that meeting or encouraged me to reach out to my union. I wish my colleagues had the courage to work with my administrator to change our school’s culture.

In the meeting, I told my administrator that I stood by our email. He disagreed with our statement about rape culture because no one was raped and the situation “hadn’t been that serious.” He said we had done all that we could do and that we were “keeping a close eye” on the students. I repeated that I still felt strongly that we needed to do some educating and he again disagreed. It was in that moment that I realized I wasn’t going to get anywhere with him. Not today, not next year, not ever. In that moment I decided to leave that school.

I walked back to my classroom feeling cold and nauseated. I sat at my computer and began filling out the application for a transfer. It made me sick to think of continuing to work for an administrator with so little respect for students’ voices and needs. I completed the application to transfer and felt such tension on my heart. I was hesitant to leave the school I had called home for two years. I was hesitant to leave the staff that supported me through my first two years of teaching. I did not want to leave the families who I had grown to know and love as my own. And more than anything, I did not want to leave my students. But I felt that I needed to leave before this situation changed me, before it hurt me beyond repair.

I know that leaving isn’t always the answer. For me, at this time in my career, and because of the history with that administrator, it was my answer. With this incident, something in me broke. I lost my momentum, my energy, and my drive. I could not picture myself thriving at that school anymore.

In a perfect world, I would have wanted my principal to do many things differently. I would have wanted him to acknowledge my student and her situation — acknowledge that she was hurting and validated her hurt. I would have wanted him to acknowledge me as a professional and that I came to him with a tough problem. I would have even been fine if he had referred me to the FLASH curriculum or to colleagues who teach that for support. I would have appreciated him problem-solving with me about my conversation with students or making classroom suggestions I might implement. I would even have appreciated my principal simply admitting that he didn’t know what to do and showing me respect by listening.

But I also realize that I could have tackled the situation differently as well, by reaching out to my colleagues to brainstorm and plan with me, and by reaching out to my union to stand with me when I feared for my job. I learned the valuable lesson that, when it comes to the essential task of advocating for our students, we cannot do it alone.