Building the School-to-Abolition Pipeline

A high school teacher explains how restorative justice helps students envision a different model of justice and community at school.

A high school teacher explains how restorative justice helps students envision a different model of justice and community at school.

On May 31, 1921, white mobs terrorized the Black community of Greenwood in North Tulsa, Oklahoma. Known as Black Wall Street, the area teemed with prosperous businesses and cultural sites. […]

This content is restricted to subscribers

High-stakes tests have not only failed to achieve racial equality in schooling, they’ve also made it worse for students of color.

In an era when a U.S. president calls Haiti and African nations shithole countries; a time when hate crimes are on the rise; a time when Black students are suspended at four times the rate of white students; and a time when we have lost 26,000 Black teachers since 2002, building a movement for racial justice in the schools is an urgent task. Black lives will matter at schools only when this movement becomes a mass uprising that unites the power of educator unions and families to transform public education.

After teachers label her son’s behavior as problematic and try to have him evaluated by a psychologist, a Black parent uncovers why schools fail Black boys and begins organizing her community to challenge practices detrimental to them.

We asked a group of radical educators to weigh in on what they hoped would be part of any 2020 presidential candidate’s education platform.

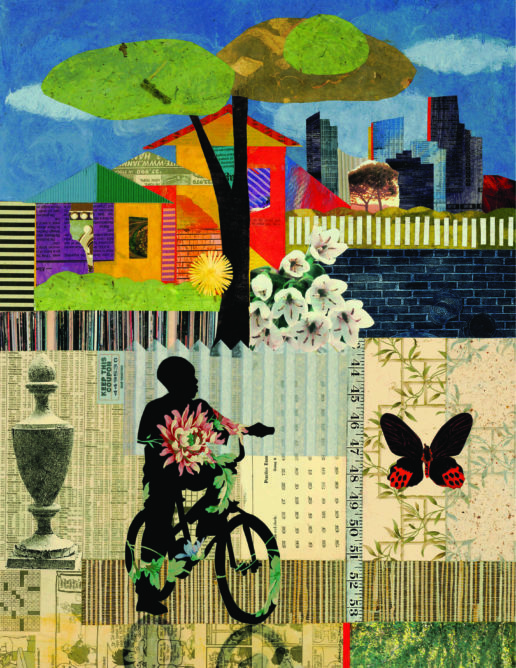

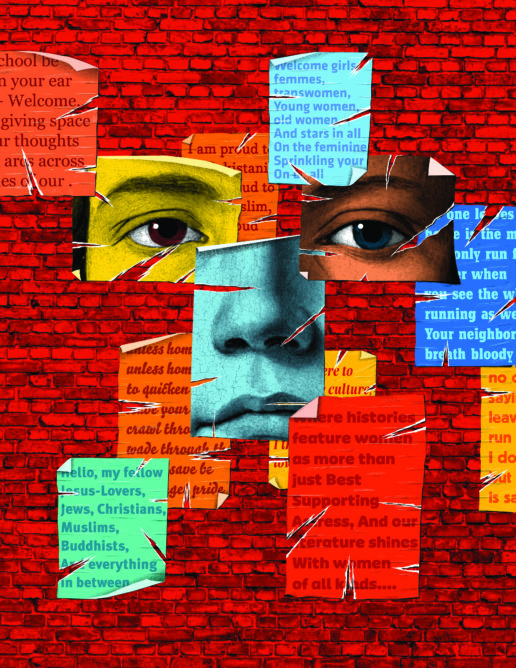

A teacher creates a welcome poems lesson to celebrate the diversity of students — and with students.

“We have something to tell you but we’re worried about getting you too involved. We don’t want to get you in trouble,” Baylee and Zaida whispered excitedly as they wiggled through the crack in my classroom door on my prep. I was confused to see them in such high spirits because earlier in the day they had been crushed by news from our administration. For more than two months they had been part of our Restorative Justice club that had been planning two half-day workshops around women empowerment for female-identifying students and toxic masculinity for male-identifying students. The club of 11 demographically diverse students had been urging adults in our building to do something about sexual harassment since October, when they made sexual assault and harassment their Restorative Justice club theme of the month and visited 9th grade classes to lead circles on the topic. This opened up a door for 9th graders to continue to reach out to upperclassmen about the harassment they were facing.

During a recent conversation, a former high school classmate said, “I always wondered why you left Eureka. I heard that something shameful happened, but I never knew what it was.”

Yes, something shameful happened. My former husband beat me in front of the Catholic Church in downtown Eureka. He tore hunks of hair from my scalp, broke my nose, and battered my body. It wasn’t the first time during the nine months of our marriage. When he fell into a drunken sleep, I found the keys he used to keep me locked inside and I fled, wearing a bikini and a bloodied white fisherman’s sweater. For those nine months I had lived in fear of his hands, of drives into the country where he might kill me and bury my body. I lived in fear that if I fled, he might harm my mother or my sister.

I carried that fear and shame around for years. Because even though I left the marriage and the abuse, people said things like “I’d never let some man beat me.” There was no way to tell them the whole story: How growing up and “getting a man” was the goal, how making a marriage work was my responsibility, how failure was a stigma I couldn’t bear.

A middle school teacher describes the trauma experienced by his students over the year and struggles to create meaningful hope rather than slogans.

As we return to our schools this fall, we need to rededicate ourselves to building an education system and a society that values Black lives.

Teachers at one Seattle school show the important role educators have to play in the movement for Black lives, in part by creating a Black Lives Matter at School day, having 3,000 teachers wear Black Lives Matter T-shirts, and responding together to issues like the death of Charleena Lyles.