Tulsa and the Fight for Reparations

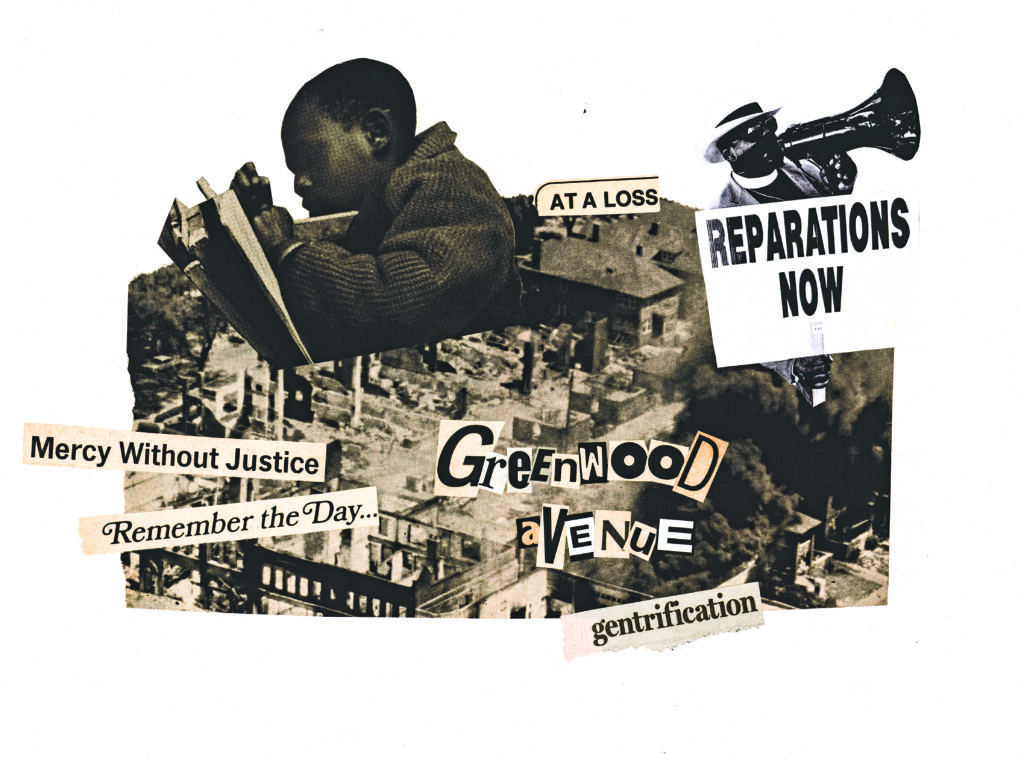

Illustrator: Adeshola Makinde

On May 31, 1921, white mobs terrorized the Black community of Greenwood in North Tulsa, Oklahoma. Known as Black Wall Street, the area teemed with prosperous businesses and cultural sites. The armed vigilantes, many of them deputized KKK members, burned the community to the ground and murdered more than 300 people — many buried in mass graves that are just now being uncovered. The destruction: 40 square blocks of 1,265 homes looted and set on fire, along with hospitals, schools, and churches owned primarily by African Americans; 150 businesses leveled by fire and, in some instances, incendiary devices dropped from the air; 6,000 Black Tulsans arrested, detained, and released only upon being vouched for by a white employer and/or citizen; 9,000 Black Tulsans left homeless, living in tents well into the winter of 1921.

The centennial of the Tulsa Massacre is a time to teach about the horrific events of those few days at the end of May and beginning of June 1921. Tulsa is a glaring historical example of police violence, mob rule, theft of Black land, and the destruction of Black wealth. And it continues today. What happened in Tulsa is not an isolated moment of white rage, but should be seen — and should be taught — as part of a pattern of white supremacy and African American dispossession.

This dispossession, and its resulting racial inequality, lives in our communities and in our classrooms. Median Black wealth in the United States — a more meaningful statistic than income — is about 10 percent of the wealth held by white people. To honor the Tulsa Massacre victims and to come to grips with the broader legacy of white supremacy requires educators to address contemporary demands for reparations. It’s an issue of racial and economic justice, but also of educational justice. Our society’s failure to enact meaningful reparations for slavery and the subsequent theft of Black wealth especially victimizes Black children. This is our issue: Educators need to respond in our classrooms, and also in our unions, where we can raise demands for reparations legislation.

Following the massacre, police jailed hundreds of Tulsa’s Black citizens. No white person was arrested. There was no restitution of any kind, not even fulfillment of insurance policies. The all-white elected city leaders rushed through ordinances to make rebuilding nearly impossible, while Black survivors tried to rebuild their lives from tents.

In 1997, Oklahoma State Representative Don Ross proposed reparations totaling $5 million for survivors and descendants. That same year the Tulsa Race Riot Commission, initiated in the Oklahoma legislature by Rep. Ross and Sen. Maxine Horner, began meeting. The commission produced a 2001 report arguing for reparations, but the state legislature and the city of Tulsa blocked any reparations to the survivors.

In February 2003, a legal team led by Harvard law professor Charles Ogletree Jr. and Johnnie Cochran filed a reparations lawsuit against Oklahoma and the city of Tulsa on behalf of the survivors and descendants of the massacre. They based their suit on the findings of the 2001 Tulsa Race Riot Commission report. The courts cited the statute of limitations to reject the claim.

In the words of Prof. Ogletree, Tulsa has become “ground zero” in the fight for reparations for Black America. Community art and education initiatives have encouraged reflection on the history of Greenwood and beyond. Educators in Tulsa Public Schools teach about Black Wall Street and the 1921 massacre. Unlike the conspiracy of silence experienced for years following the massacre, the public can now find books, films, and curricula describing this history. The HBO series Watchmen introduced millions of viewers to the horrific events in Tulsa.

The resilience of Black Tulsans is also a major part of this story. In the heart of “deep Greenwood,” the Greenwood Cultural Center serves as testimony to Oklahoma’s Black workers, farmers, entrepreneurs, and everyone who made up the historic Black Wall Street and the many surrounding Black townships. It brings Greenwood’s history to life to promote and preserve African American culture and heritage.

Despite growing attention, no legislative body is seriously considering reparations. The Black citizens of Greenwood worked to rebuild the community following the destruction in 1921. But segregationists thwarted their efforts again and again through urban renewal, eminent domain, and colonization of land and businesses. The city built a baseball stadium there and Oklahoma State University built a satellite campus. The Oklahoma state highway system ran a major arterial through the community.

The story of Greenwood and the Tulsa Massacre is an extreme episode in U.S. history, but it reflects the evolving system of white supremacy that once defined Black bodies as property and persisted in the form of lynchings during the 100 years of Jim Crow. Black communities saw the mob and the whip replaced by government-sponsored programs like COINTELPRO, the war on drugs, mass incarceration, unjust policing, and structural policies — like redlining, urban renewal, and more — that maintain racial segregation.

Reparations

It is time to reckon with the historical costs of white supremacy on Black life — in our economy and in our curriculum.

To address the violence, the theft, the discrimination, and untold harm will take economic restitution. Reparations have always been a demand of Black activists. Even before the end of the Civil War, General William T. Sherman issued Special Field Orders No. 15, dividing about 400,000 acres among formerly enslaved people in response to their demand for land; only a few months later, President Andrew Johnson reversed this gesture of restitution. Activist Callie House, a formerly enslaved woman, traveled the country lobbying Congress for a modest pension for the freed men and women that was never paid.

But reparations are not unheard of. Federal and local governments, along with private institutions and individuals, have paid out legal settlements, made individual and class action monetary payments, redefined land ownership and boundaries, designed scholarships, and implemented a variety of other efforts to repair past harm.

The House of Representatives has held hearings on H.R. 40, the Commission to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African Americans Act, originally proposed by John Conyers Jr. in 1989. Members of Congress have reintroduced H.R. 40 since then. Texas Democratic Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee, the resolution’s most recent sponsor, put the bill forward in 2019 and again in January. It is long past time for our elected officials to approve the Commission to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African Americans Act and begin the process of paying reparations for slavery.

The reparations demand has also sparked significant scholarship and literature. Recent contributors include William Darity Jr. and A. Kirsten Mullen, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Nikole Hannah-Jones, and Heather McGhee. The vmovement saw some success in 1995 when the Florida state legislature paid reparations for the attack on the Rosewood community, the murder of many of its citizens, and the destruction of Black-owned property. In 2015, activists in Chicago won reparations for victims of the Chicago Police Department’s campaign of torture. They demanded payment to victims and curriculum about the Police Department’s campaign of torture and its relation to white supremacy. [See “Reparations Can Be Won — and Must Be Taught,” by Jen Johnson, in the Winter 2020–21 issue of Rethinking Schools.]

Teaching Tulsa

The Black Lives Matter movement has brought to the fore the demand to dismantle white supremacy. For many school districts, this has led to reevaluations of curriculum, including participating in the Black Lives Matter at School Week of Action and Year of Purpose.

Tulsa Public Schools and other Oklahoma districts have introduced curriculum about the massacre. In Tulsa, all staff participate in four 70-minute professional development sessions on the destruction of Black Wall Street and the history of Greenwood, in preparation for teaching curriculum at all grade levels. The material emphasizes the perseverance and resistance of Tulsa’s and Oklahoma’s Black communities in the face of white supremacy. Issues of gentrification, loss of wealth, segregation, and reparations are part of the curriculum.

But the Tulsa Massacre centennial is a time for all educators, not just those in Oklahoma, to teach about the history of white supremacy and its contemporary legacies. When looking at Greenwood’s destruction, it is also important to contextualize “Oklahoma” in the larger history of settler colonialism and the genocide of Indigenous people. Students across the country should answer the question “What do reparations look like for the original sins of the United States — dispossession and enslavement?”

A valuable place to start for middle and high school teachers are lessons by Linda Christensen at the Zinn Education Project: “Burning Tulsa: The Legacy of Black Dispossession” and “Burned Out of Homes and History: Unearthing the Silenced Voices of the Tulsa Massacre.” These cover the buildup to the massacre and the experience of Greenwood citizens. Accompanying that is the graphic novel The Massacre of Black Wall Street published by the Atlantic that tells the story of the tragedy and provides additional essays.

Another lesson is “How to Make Amends: A Lesson on Reparations” by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca, Alex Stegner, Chris Buehler, Angela DiPasquale, and Tom McKenna. In this mixer role play, students encounter examples of reparations throughout history — from cash payments to land settlements to state apologies.

Unfortunately, examples of successful reparation struggles shrink in comparison to the countless massacres in U.S. history that have been buried by the dominant narrative of white supremacy in our nation’s textbooks.

By connecting the Tulsa Centennial to other massacres and other examples of reparations, educators can bring these experiences of oppression and resistance closer to home. Such teaching can strengthen the growing calls for reparations on a national level. We can think of no better way to commemorate the historic resistance of Black Tulsans a century ago.

Illustrator Adeshola Makinde’s work can be seen at adesholamakinde.com.

Subscribe to Rethinking Schools at rethinkingschools.com/subscribe