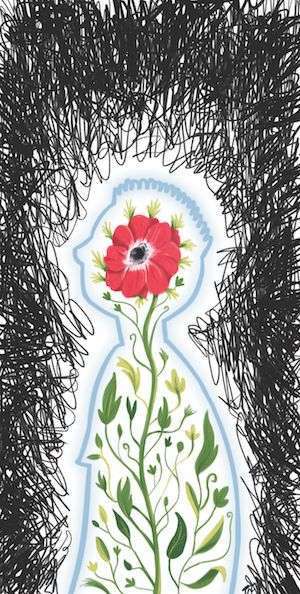

Unfolding Hope in a Chicago School

Illustrator: Shannon Wright

As I returned to my 7th- and 8th-grade classroom in January after a much-needed winter break, part of me was hoping to leave Donald Trump—and much of 2016—behind. Sure, I knew he would be inaugurated soon. I knew his already ubiquitous presence would become even more suffocating. And I feared his frightening campaign promises would soon land brutally on people’s lives—including the lives of my students.

But he had already wormed his way into so many of our lessons over the past year that I thought we were ready, at least for a while, to turn to other topics, other themes.

I should have known better. By the end of his first week in office, Trump had already signed an executive order to begin building a wall along the Mexican border, threatened to “send in the feds” if Chicago’s gun violence numbers didn’t improve, blocked Syrian refugees from entering the United States, and temporarily banned immigration from seven majority Muslim countries. It was impossible for us to look away.

For my students—mostly children of immigrants from Mexico, along with a few Central American and Muslim immigrants, living on Chicago’s South Side—the worries that accompanied Trump’s flurry of first-week actions were not new. Throughout 2016, as the bizarre presidential election and the spiraling levels of gun violence in some of Chicago’s most forgotten communities made headlines, my students never had the luxury granted to most white Americans, who looked on from a comfortable distance. For the kids I teach, it all played out—literally—close to home, and the accompanying loss and fear were visceral, palpable.

As 2016 began, late-night talk shows and social media were having plenty of fun with the notion of a Trump presidency. But my students were already anxious. The possibility of Trump landing in the White House had never felt like a joke to them and, as the months went by, their concerns grew. They listened as he categorically disparaged Mexicans and Muslims, as he threatened to end birthright citizenship, as he demonized Black and Brown Chicago, as he repeatedly promised to build a wall. To my students, these were neither throwaway stump speech lines nor laughable proposals. They were direct threats.

“Mr. Michie,” one of my students asked during class, “if Donald Trump wins and my mom gets deported, can I come live with you and your family?”

“I don’t think that’s gonna happen,” I said. “If it does, though, we’ll figure something out. You’re gonna be OK. Don’t worry.”

But he did worry. Despite the reassurances of teachers, despite the polls, he was fearful, as were many of my students, of what might be. But they were also afraid of what had been, of what already was.

On a Monday evening in early May, I got a text from a former student: “Hey Mr. Michie I don’t know if you had heard they just shot Leo the 7th grader.”

No, I thought. Please, no. Leo was in my homeroom—a bright, quiet kid who loved playing basketball in the park, reading realistic fiction, and making his classmates laugh. Earlier that day, we’d stood back to back in the hallway to see who was taller. I still had him by a half inch. “I bet you’ll pass me by the end of the year,” I’d said.

No, no, no. Let him be OK.

A few minutes later, another text: “Mr. Michie he passed away. They just texted me right now telling me that he didn’t pull through.”

I had been to the funerals of several former students over the years. But I’d never had a current student killed, never had to face all his friends in class the next morning. I wasn’t sure what to say, what to do, how to proceed. I knew information traveled fast in the neighborhood—it always had, even before Facebook or texting—so I didn’t think I’d be the one to break the news to any of my students. But when one boy ambled in, hair tousled as if he’d woken up 10 minutes earlier, I could tell by the way he looked around at the awkward stillness of his classmates that he had no inkling. Telling him was one of the toughest things I’ve had to do in my 20-plus years as a teacher.

My colleagues and I decided to let all the 7th and 8th graders spend the entire morning out in the hallway. We hugged. We cried. We stood around in clusters, speaking in whispers, still stunned. Later, my homeroom students gathered chairs in a circle and shared. We meditated, as we do every day. And we created a community memorial to Leo in the hallway, with photos, drawings, poems, and remembrances. A smaller version of it still graces our classroom all these months later.

The week after Leo was killed, a class of 2nd graders—along with their teacher, Erika Gomez, who grew up in the neighborhood and attended our school—slowly filed into our classroom in the middle of a social studies lesson. My students watched, confused. “What are they doing?” one student asked aloud.

When the last of the children had taken their places in a semicircle that embraced the older students, three stepped forward.

“We know you are really sad about your friend, Leonardo,” a girl said.

“But we want you to know that there is hope. Don’t lose hope,” another added. “So we made little presents for you to keep and to know that life goes on.”

For the next few minutes, the 2nd graders made their way around the room, handing out cards they’d made for the teens. “I’m sorry for your loss,” one chubby-cheeked boy said. Near him, a pair of girls hugged as tears rolled down the 8th grader’s cheeks. She wiped them away, smiled, and gave her card-bearer another tight squeeze.

It had been an unimaginably difficult two weeks, and the surprise visit had come at just the right time. At some point, we’d need to think again about the root causes of violence in the neighborhood, about what the city needed to do to support young people in communities like ours, about our own roles bringing about change. But at that moment, we needed to remember Leo. We needed to hold on to each other. We needed just what those 2nd graders provided.

That any school-based learning can happen when kids are experiencing such emotional upheaval, such an avalanche of sadness and fear, is something akin to a miracle. But it does. Young people are resilient—far more than they should have to be—and we do our best to move forward. As in many middle school classrooms, my students are by turns deeply engaged, flat-out bored, lost in reflection, or writhing in uproarious laughter. They write poems and read novels and explore big questions like “What is the meaning of patriotism?” and “What is the role of the media in a democracy?”

In October, in the midst of a unit on the presidential election, my social studies classes watched Khizr Khan’s speech from the Democratic Convention. Almost none of them had seen it before, and when Khan pulled a slim booklet out of his jacket pocket and said to the camera, “Donald Trump . . . let me ask you: Have you even read the United States Constitution? I will gladly lend you my copy,” their roar of applause seemed to shake the walls. One girl turned to me and said, “That right there gave me chills.”

The morning of November 9, the electricity generated by the Khan video was a distant memory. Like much of the United States, many of my students believed that Hillary Clinton would win. Or maybe they just wanted to believe it. Most of them weren’t huge Clinton fans (many had favored Bernie Sanders during the primary season), but Trump was frightening.

When I asked if anybody wanted to share how they were feeling in the wake of the results, few did. So I asked each student to give me just one word: Angry. Worried. Afraid. Disappointed.

Later in the period, when we looked at the exit polls broken down by race, it was no surprise who had disappointed them. Trump had won only the white vote, while losing in a landslide among everyone else.

My students are not naive. I don’t think they look to electoral politics as a simple balm for their hurts or struggles. They are keen observers of current events and history, and are quick to detect injustices perpetrated by those in power, whether we’re discussing the Dawes Act of 1887 or the recent cover-up of the Laquan McDonald shooting in Chicago. But they are also, on the whole, not jaded. Although they note the hypocrisies, and live out the stark differences between the United States of textbook mythology and the United States of their backyard, many want to believe that the country’s people will, when it really matters, do right by them. In that sense, the presidential election was another crushing loss in a year of crushing losses.

As painful as Leo’s death had been, it wasn’t the first, or the last, to shake our school’s community during the past year. Sidewalk altars became a recurring feature of the neighborhood landscape, their wilting flowers and Virgen de Guadalupe prayer candles serving as reminders of the fragility of life for kids who walked past each day. Two of those killed were the older brothers of a current 8th grader. Five had once been students at our school. The oldest among them was just 22.

So, were they gang members? I can almost see that question bubbling to the surface in the minds of some readers. My short answer is that it doesn’t matter. They were young—most of them still teenagers—and now they are gone. Asking if they were gang members seems little more than a pretext for concluding that their deaths were justified, or at least undeserving of sympathy. It’s the same line of thinking, in reverse, that prompts journalists to alert readers that a murdered teen was an “honor student”—as if a kid who failed a class or had a C average is somehow expendable. Of the young people our school’s community lost this year, some were gang-affiliated. Others were not. Either way, the questions we should be asking in the wake of such violence are deeper ones: Why do so many Black and Latino young men feel a sense of hopelessness or despair? What can schools do to better embrace and connect with kids on the margins? Where are the job opportunities and mental health supports for young people in our city’s neediest neighborhoods?

Asking good questions is, of course, part of the territory for teachers. But for me, the most urgent question of the year was not part of any unit plan or asked by any adult at our school. It was posed by an 8th grader toward the end of an assembly that addressed the violence in our community, how it was affecting us, and how we might respond. The young girl raised her hand tentatively before asking, “How does hope unfold?” The philosophical turn of the question, as well as its unusual construction, took everyone by surprise. If anyone responded, I don’t remember what they said. But the question stuck with me: How does hope unfold? The image it brings to mind, for me at least, is of hope as a process, a series of actions, that build on one another over time. It resonates with me in ways that similar questions, such as “Where do we find hope?” do not.

For many educators, the answer to the question “Where do we find hope?” is often simple and obvious: the kids. We find hope in our students, the next generation. It’s a clich, but I’ve said it myself many times, and there is truth to be found in the words. Still, the events of this year have pushed me to reconsider that response, to wonder if it is, in some ways, a cop-out for adults, a way to place a weight onto the shoulders of young people who shouldn’t have to carry it. That thought was echoed by one of my 8th-grade students, who closed a poem with these words:

They tell me to have hope, that everything is going to be OK.

But how can I believe them? How can I convince myself that everything’s gon’ be alright?

How can you ask me to have hope when bodies are being dropped day after day?

….

If there is a way to get hope,

teach me,teach us.

That, in turn, may be too formidable a load for teachers to bear alone. In times of tragedy, we all flail about, full of uncertainty. The only real way forward, it seems, is to trudge through the losses and pain hand in hand.

And that we continue to do. A colleague down the hall has instituted peace circles in her classroom. Our school administration set aside money for therapists to support students’ emotional health, and devoted an entire professional development session to teacher wellness. In late November, in response to the election results, a number of students and teachers participated in a “We Belong” unity march and rally, where one of our 8th graders delivered a powerful speech in support of her undocumented brother.

Outside the school’s walls, the neighborhood is, as always, full of beautiful people and fierce love. Gun violence and gangs do not define it. Kids play soccer in the park. Some go to confirmation classes or play in a marimba ensemble at the local parish. Mothers lead parenting classes. A weekly reflections group draws 15 or so young men who discuss their struggles and ways to address them. (“We don’t need more police. We need jobs.”)

And in the classroom, we do our best to keep keeping on. We begin our meditation every day by remembering Leo. We explore the historical oppression of Native people by the U.S. government, and the lessons we can learn from their resistance. We read the words of heroic Americans like Ida B. Wells and Malcolm X, and analyze their meaning for the struggles of today. We may not always be sure where we’re headed, but the challenge is clear: Day by day, piece by piece, unfold hope. Together.