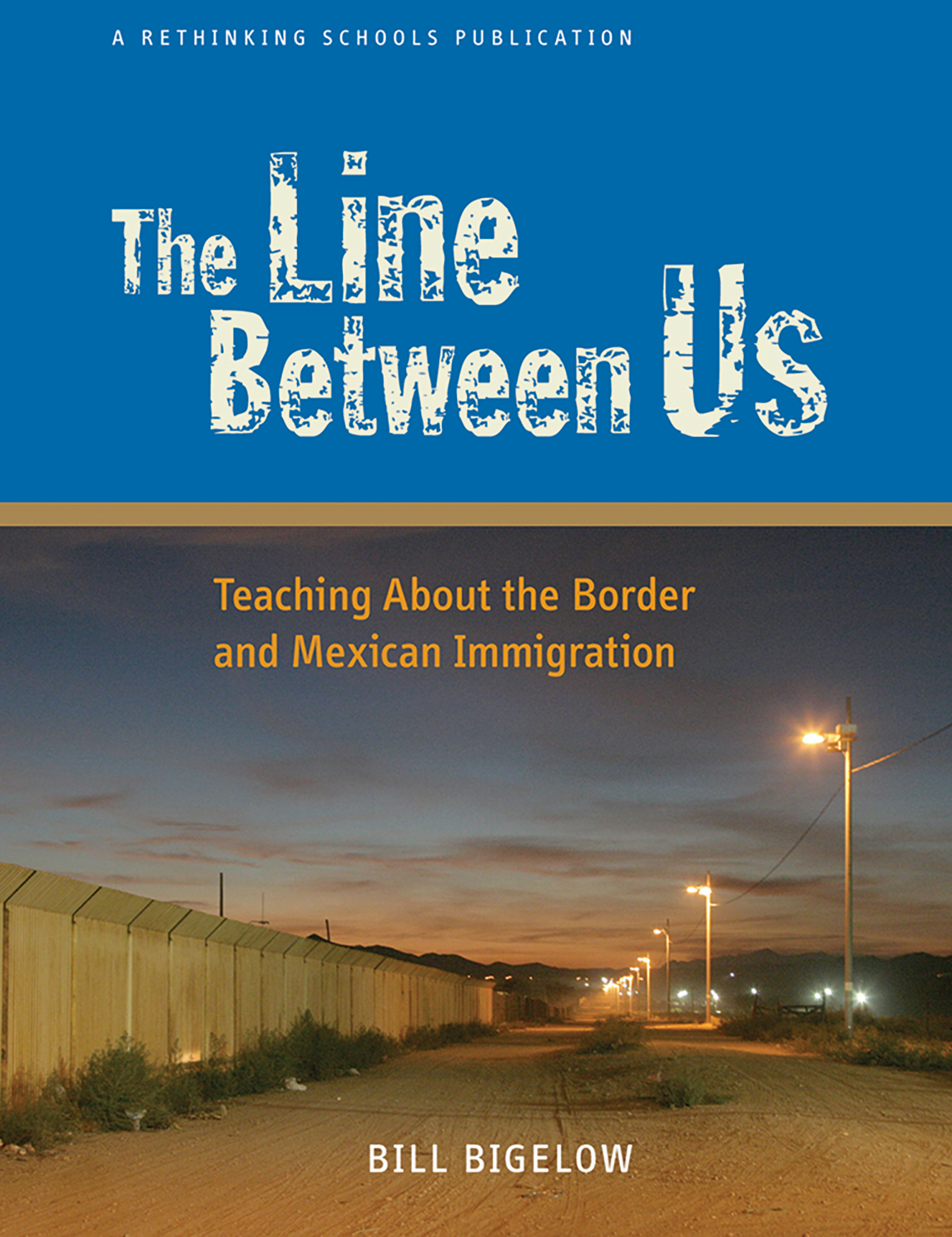

The Line Between Us explores the history of U.S-Mexican relations and the roots of Mexican immigration, all in the context of the global economy. And it shows how teachers can help students understand the immigrant experience and the drama of border life.

But The Line Between Us is about more than Mexican immigration and border issues. It’s about imaginative and creative teaching that gets students to care about the world. Using role-plays, stories, poetry, improvisations, simulations and video, veteran teacher Bill Bigelow demonstrates how to combine lively teaching with critical analysis.

The Line Between Us is a book for teachers, adult educators, community organizers and anyone who hopes to teach and learn, about these important issues.

“Bill Bigelow has written a wonderful book on critical teaching, filled with examples, resources, and how to transform theory into practice. With ingenuity and integrity, Bigelow pushes to the limits of what’s possible in public education.”

—Ira Shor, City University of NY Graduate School; author (with Paulo Freire) of A Pedagogy for Liberation

“This is exactly what we need—teachings on Mexican migration to the U.S., one of the most vital issues we face today. It’s about the momentous clashes of economics, politics, and race. The Line Between Us has the clarity and weight to guide us through these complex and perplexing concerns.”

—Luis J. Rodríguez, Acclaimed author of Always Running and editor of the online Chicano magazine, Xispas.com

“A greatly-needed guide to help break down the growing divisions in this country. As the daughter of a Mexican immigrant, remembering how the next-door neighbor’s Anglo daughter was not allowed to play with me, I can only wish young people had been exposed to the thought-provoking information and ideas contained in The Line Between Us.”

—Elizabeth (Betitta) Martínez, Chicana activist, educator, and author of 500 Años del Pueblo Chicano/500 Years of Chicano History in Pictures

“At a time when we are increasingly separated by perceptions of ‘us and them,’ The Line Between Us helps us understand the global ‘us.’ The book invites students to connect the dots between social, environmental, and political issues, and discover our common ground across borders. Equally important, it goes beyond exposing tragedy and suffering, and encourages students to discover hope and courage in stories of resistance.”

—Medea Benjamin, Co-founder, Global Exchange and Code Pink

“We need a shared vision of a different type of border that would protect communities, migrants and human rights everywhere. The Line Between Us is an important contribution to discuss and learn about the current border and imagine together the one we need.”

—Arnoldo Garcia, National Network for Immigrant and Refugee Rights

The Line Between Us

Acknowledgments-v

Introduction-1

Running to America by Luis Rodríguez-3

Section 1: Teaching About ‘Them’ and ‘Us’-5

One: The Border-7

Two: Born in War-11

Three: Immigrants and Empathy-15

What Is Neoliberalism? by Arnoldo Garcia and Elizabeth Martínez-20

How We See the World by the Zapatista Army of National Liberation-24

Four: NAFTA and the Roots of Migration-19

Five: Free Trade’s Intimate Impact-28

Six: ‘They’re Taking Our Jobs’-34

Section 2: Historical Roots of the Border-41

The U.S.-Mexico War Tea Party/’We Take Nothing by Conquest, Thank God’-43

We Take Nothing by Conquest, Thank God by Howard Zinn-53

Heart of Hunger by Martín Espada-60

Section 3: NAFTA’s Impact-61

The NAFTA Role Play: ‘Mexico-United States Free Trade Conference’-63

Rethinking the NAFTA Record-77

After NAFTA: Mexico, a Ship on Fire-79

Section 4: First Crossing-81

Crossing Borders, Building Empathy by Bob Peterson-83

First Crossing by Pam Muñoz Ryan-87

Section 5: Life on the Border-95

Reading Chilpancingo by Linda Christensen- 97

A Toxic Legacy on the Mexican Border by Kevin Sullivan-102

The Transnational Capital Auction-105

The Women of Juárez by Amalia Ortiz-111

Mexico Border Improvisations -113

Section 6: Resources-123

More Teaching Ideas-125

Mexico in Rethinking Globalization-128

Books and Curricula-130

Elementary Books with a Conscience by Kelley Dawson Salas-132

Videos with a Conscience-134

Organizations, Websites, Journals-143

Index-146

The Line Between Us Introduction

by Bill Bigelow

I was born and raised in what was once Mexico. The county courthouse was in San Rafael, we did our shopping in Corte Madera, I went to seventh and eighth grades in the neighborhood of Del Mar on Avenida Miraflores, and we looked across the bay to the closest big city, San Francisco. I grew up surrounded by linguistic memories of Mexico.

Mexican place names have always been welcome here. But the U.S. attitude toward Mexican people and Mexico itself has been more ambivalent. And these days, the border between Mexico and the United States has grown increasingly tense.

Since the mid-1980s, I’ve traveled to Mexico 12 times. The most recent trips — five to Tijuana and the border, one to Chiapas in southern Mexico — gave rise to the lessons in this book. This curriculum project, in turn, grew out of work on the Rethinking Schools book Rethinking Globalization: Teaching for Justice in an Unjust World. Throughout, I’ve sought to engage students in a search for connections: between Third World debt and rainforest destruction, between food exports and sweatshops, between free trade and global warming, between social analysis and imagining alternatives. And it’s been a search to discover which lessons resonate with students, which touch their hearts, which make them want to dig deeper.

The relationship between Mexico and the United States is a good place to focus a rethinking globalization lens. These days the anti-immigrant rhetoric is growing even more shrill — from quasi-vigilante groups like the Minutemen, to think tanks like the Center for Immigration Studies that mask their nativism in a statistic-dense scholarly discourse, to congresspeople who demand, “We need to get serious about enforcement.” Our students are surrounded by a culture that exposes them to some very bad “teaching” about Mexico and immigration. Too often, the conversation is abstract and centers on immigration disconnected from its history and from its root causes. The questions commonly asked — e.g., Does our economy benefit or suffer from immigration? Should border security be tightened or should there be a new guest worker program? Should bilingual education be banned? — tend to be narrow and ahistorical.

In The Line Between Us, I offer my own classroom experiences, as well as teaching reflections of Rethinking Schools editors Linda Christensen and Bob Peterson, to suggest the importance of a connected inquiry. Thus, the book features lessons and readings on the history of the border itself — the product of a war pursued by a slave-owning president, James K. Polk, who misrepresented intelligence, lied about his intentions, and provoked and invaded a sovereign country. The line between Mexico and the United States appears a bit less sacred when looked at in its historical context.

As lessons on the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) reveal, the line between us has become less of a barrier to investment and trade. But the huge number of migrants seeking to cross the border is inexplicable without analyzing the impact of this so-called free trade. “The NAFTA Role Play” activities in the book aim to lay the groundwork for students to connect these phenomena. The link between trade and immigration may be news to some in the United States, but not to observers in Mexico. Three years before NAFTA took effect, José Luis Calva of the National University of Mexico, predicted, “If the governments and legislatures of the three countries [Mexico, the United States, and Canada] agree to liberalize trade in agricultural goods, U.S. citizens should be prepared to receive some 15 million Mexican migrants. The Border Patrol will be unable to detain them, and even a new iron curtain, rising on the border at a moment when the Cold War has given way to economic warfare among nations, will buckle under the weight of millions of Mexicans thrown off their lands by free trade.” Prescient remarks. Students need to explore these kinds of connections.

“Reading Chilpancingo,” “The Transnational Capital Auction,” and “Border Improvisations” encourage students to consider how intimate details of people’s lives are framed by the imperatives of a global economic system. The jobs that people have or don’t have in maquiladora zones along the U.S.-Mexico border, the wages they receive or, for that matter, the quality of the air they breathe and the water they drink, are connected to investment decisions in a global game of profit maximization.

This is the kind of historical and contextual inquiry that students need to engage in if they are to avoid the immigrant scapegoating that distorts so much thinking these days. It is also the approach that informs the lessons in this book.

The Lines Between Us

The book is called The Line Between Us, but in fact, the material here traces many lines between us. The most obvious are the multiple walls between the United States and Mexico. However, the lines inside Mexico are also growing more pronounced — between men and women, between countryside and cities, between rich and poor. When Bob Peterson and I were in Chiapas in July 2005, people told us that villages there increasingly are being emptied of the men, who are fleeing low prices for their crops and seeking work in sprawling Mexican cities or in the United States. Entire villages are now mostly women and children, the lines slicing relationships and families. Mexico’s gulf between the haves and the have-nots is also growing. Mexico has long been one of the most unequal countries in the world, but it’s getting worse.

The line between the rich and poor in Mexico mirrors the inequality between the United States and Mexico. The typical U.S. hourly wage equals the typical Mexican daily wage. It’s a line that separates people who have a right to organize a union (albeit with significant limitations) and those who, for the most part, have little ability to secure authentic union representation. And for too many companies, the line between the United States and Mexico signifies the line between environmental regulations and a toxic free-for-all, highlighted in Linda Christensen’s “Reading Chilpancingo,” and Kevin Sullivan’s “A Toxic Legacy on the Mexican Border.”

In the United States, the border legitimates lines between legal and illegal residents, and all that these categories entail. I explore these lines in “Teaching About ‘Them’ and ‘Us,'” recounting my students’ reactions to my curriculum. It’s a line between those who live in fear of deportation and those who don’t, between those who risked their lives to get here — like Marco and his father in Pam Muñoz Ryan’s “First Crossing” — and those who didn’t.

But these are human-made lines, so they can also be unmade. It’s easy to focus on the negative, because the injustice seems infinite. Yet the curriculum itself is an expression of hope and features people of courage and conscience: cross-border environmental justice organizers, collectively owned ejido communities that refuse to sell or leave their land, the American Friends Service Committee activists who monitor the U.S. Border Patrol, poets and artists who speak truth to power, and ordinary people trying to live dignified lives.

The material here is still a work in progress. For instance, I’m in the early stages of writing lessons on the history of U.S. immigration policy. Much more could and should be written about how students here can themselves contribute, however modestly, to putting the relationship between Mexico and the United States on a more just footing. I still struggle with how to get my non-immigrant students to resist fearful responses to immigration and to see their own self-interest more expansively. But in the face of proposals to criminalize immigration as never before, to build more and bigger walls, and to “develop” Mexico and Central America with even freer free trade, the issues discussed in this book have taken on greater urgency; the benefits of waiting to publish would have been offset by the costs of staying silent at a critical time.

These issues aren’t going away anytime soon. To the contrary. So long as the line between us marks such dramatic inequality, and so long as the models of development that predominate in Mexico mostly benefit the rich on both sides of the border, the south-to-north migration is here to stay. Teachers of conscience will need one another as we fashion our response. This book is Rethinking Schools’ contribution to a curricular conversation that we hope will find a wider audience. It’s our attempt to erase some of the lines between us.

Last Updated Spring 2006

These links are organized by the page numbers from The Line Between Us where the materials are mentioned.

Page 8 – Sign up for the Rethinking Schools listserv

Page 16 – Immigrant Interview Write-up Assignment

Page 16 – Immigrant Interview Write-up Checklist

Page 30 – Interior Monologue prompt

Page 30 – Poem: “Valentine’s Day at Casa del Migrante” by Bob Peterson

Page 33 – Mexico Immigration Essay Assignment

Page 33 – Mexico Immigration Essay peer edit checklist

Page 37 – Immigration Justice Alliance by Tim Swinehart and Sandra Childs

Page 66 – NAFTA Role Play Follow-up research handout

Page 98 – Chilpancingo photo

Page 100-101 – Links to Chilpancingo Articles:

- “Environmental Health and Toxic Waste” Vicky Funari, Sergio De La Torre, and Grupo Factor X, Maquilopolis, undated

http://www.maquilopolis.com/toxicwaste.html - “Empowerment Brings Change” Mariana Martinez, La Prensa San Diego, Sept. 20, 2002

http://www.laprensa-sandiego.org/archieve/september20-02/ejido.htm