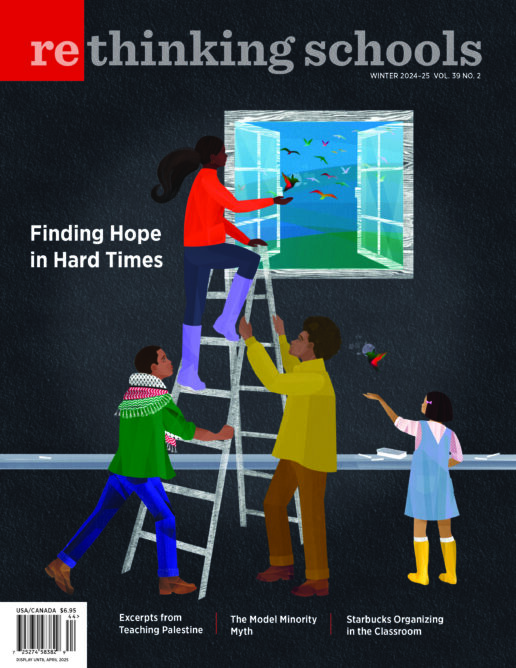

Teaching Hope in Hard Times

Illustrator: Erin Robinson

What makes public education so dangerous is that it is grounded in hope.

As the editors of our forthcoming Teaching Palestine: Lessons, Stories, Voices write, “one of the wonderful things about being an educator is that our work begins with an unshakable belief in the future. To step into a classroom is to express confidence in young people’s capacity to learn, to grow, to change, to make a difference — to do good in the world.”

Even before November’s election, these were grim times, with young people experiencing record levels of hopelessness, according to a 2023 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention survey.

No doubt we need to organize for more school counselors, social workers, in-school health professionals — and universal access to health care, including mental health. But we also need to ask: How do we teach for hope in these hard times?

We teach to remember. Times of extraordinary activism and progress have often gone side by side with leaders who have not been on the side of justice. The abolition movement grew and grew during the grimmest days of slavery, under hostile presidents and Supreme Courts. The strike waves of the 1930s began not under the Democrat Franklin Roosevelt, but under the reactionary Herbert Hoover. The Civil Rights Movement was launched with a Republican, Dwight Eisenhower, as president and racist Democrats as governors throughout the South. The Black Panther Party was born in Oakland while Ronald Reagan was governor of California, and the anti-Vietnam War movement became massive under Nixon’s presidency. And, of course, the outpouring of activism around racial justice following the murder of George Floyd occurred during the last presidency of Donald Trump.

We teach to imagine. As Kelly Hayes and Mariame Kaba write in Let This Radicalize You, “We know that hope is essential to social change because in order to make change, someone must first imagine that it can be so.” And this can happen with the youngest children, as Cristina Paul, Olivia Lozano, and Nancy Villalta demonstrate compellingly in their Rethinking Schools article “Community Building as World Building” (Winter 2023–24).

We teach that dramatic social change can emerge unexpectedly, and that fact too can be a source of hope. In her book The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks, Jeanne Theoharis tells the story of Parks’ attendance at a Highlander Center workshop in the summer of 1955. At the end of the workshop, Parks promised to continue her work with young people in Montgomery, Alabama, but predicted “that nothing would happen there because Blacks wouldn’t stick together.”

Only a few months later, Rosa Parks’ prediction was proven wrong by the Montgomery Bus Boycott, which became a foundational struggle in the Civil Rights Movement and launched Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s career as a movement leader. In fact, Black people in Montgomery did “stick together,” heroically, and made history. Stories like these — and history is filled with them — show young people that our efforts can turn into more than we can imagine. Using our anger and frustration at the daily injustices we face or witness, we take small steps forward. It can be hard to predict when the next explosion of protest will erupt.

And we teach that hope is not something found, but made. Educators have always created grassroots experiences to defy top-down mandates, share knowledge, and create together. As one teacher wrote after the 2023 Northwest Teaching for Social Justice Conference, which pulled together hundreds of educators at Parkrose High School in Portland, Oregon: It was “a soul-filling, hope-feeling, heart-touching, inspirational experience.” The NWTSJ conference was inspired by a similar teacher-organized event in San Francisco many years ago — part of a tradition of radical gatherings to define what we mean by “social justice education.”

As the poet June Jordan famously said, “We are the ones we have been waiting for.” When people of conscience find each other, these gatherings open new horizons of possibility. Every year the Zinn Education Project — a collaboration of Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change — sponsors close to 100 study groups around our book Teaching for Black Lives. These are the kind of professional gatherings that help us align our values with our educational practice — and generate hope. As one study group participant wrote, “Having a reliable and deeply thoughtful group of allies in my community was so powerful and supportive during this difficult year. I drew strength every day at school knowing that my study group colleagues were there and would be supportive of my practices.” It is worth remembering that it was a teacher study group that birthed the Chicago Caucus of Rank-and-File Educators and a version of social justice unionism that continues to inspire teachers throughout the country.

As they face Israel’s unrelenting and indiscriminate violence, Palestinians have provided crucial lessons in the practice of hope. In Teaching Palestine, we feature the work of the courageous Gazan journalist Bisan Owda. As the genocide in Gaza unfolded, Owda wrote supporters around the world: “We ask you not to lose hope, even if the world seems completely unfair and your efforts have not yet resulted in a ceasefire.” Within days of the occupations that erupted across college campuses last school year, displaced Palestinians in Gaza were writing thank you messages on their tents to college students in the United States — who had their own tents torn down by campus and city police. The solidarity between young people in the United States and Palestinians in Gaza was an exercise in creating and sharing hope for a future where genocide would not exist because all people and the planet were valued.

As attacks on anti-racist educators move to places where teachers have built significant networks — whether inside or outside of official unions — organized opposition has a wellspring of hope to draw from. This can be seen in Philadelphia, where several leading educators in the Racial Justice Organizing Committee have been targets of a campaign to label them antisemitic and remove them from the classroom for speaking out about Israel’s atrocities. A complaint launched by the Deborah Project — a law firm dedicated to expanding the fight against critical race theory by weaponizing antisemitism — led to the unassignment of award-winning Black Muslim educator Keziah Ridgeway.

But despite this campaign of harassment and being removed from Northeast High School where she had worked for eight years, Keziah told Rethinking Schools:

For someone like me who’s so used to never asking for help, I’ve recently had to. In doing so, it has opened my eyes to the true extent of community that exists. This is the community — built on integrity and respect for life — that will use all the skills at our disposal to build a world free of oppression and welcoming to all.

Building and strengthening these communities of hope is what will get us through. Students need our classrooms to be communities of hope too. Our work with young people — and with each other — needs to demonstrate that another world is possible. Finding, sharing, and teaching hope through these perilous times will help point the way there.

“Hope,” an excerpt from the introduction to Teaching Palestine: Lessons, Stories, Voices

As we look at the history of Palestine-Israel, from the beginning of the Zionist movement to the Nakba to the events today in Gaza and the West Bank, it seems reasonable to despair. But one of the wonderful things about being an educator is that our work begins with an unshakable belief in the future. To step into a classroom is to express confidence in young people’s capacity to learn, to grow, to change, to make a difference — to do good in the world. Education is anchored in hope. A book about teaching Palestine is also a book about teaching hope.

Never have there been more people in the world expressing solidarity with Palestine. Never have there been more students demanding justice for Palestinians. Never has there been more consciousness about the ongoing Nakba Palestinians have experienced. There has been a rupture in the silence about Palestine. As Reem Abuelhaj comments in “Talking to Young Children About Gaza,” “I never imagined I would walk through my neighborhood in Philadelphia and see people sitting at coffee shops wearing keffiyehs or see so many Palestinian flags in the windows of my neighbors’ homes.”

We conclude our chapter on Gaza with “Occupied by Hope,” an essay by Palestinian American poet and reporter Noor Hindi:

When I ask my father, “Is there hope?” his response is swift.

“Of course there is hope.”

“From where?” I ask.

“I haven’t let go of my hope.”

Here is the truth about being Palestinian: In this lifetime, and the one after, and the one thereafter, we will always choose Palestine. There is little that endures more than our hope.

In the face of the unimaginable, this is what I hold on to.

When we teach about Palestine, this too is what we must hold on to.