Talking to Young Children About Gaza

Illustrator: Sophia Foster-Dimino

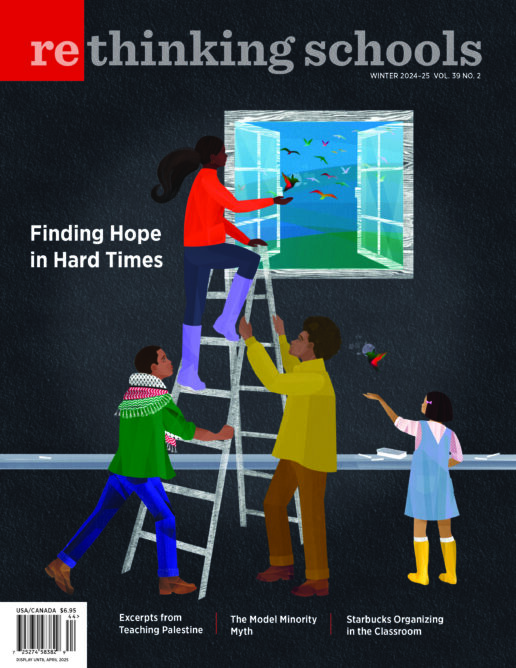

Fundamental to our work as educators and caretakers of children is an obligation to tell young people the truth about the world and give them tools to take action.

For those of us in a wave of grief as we watch Palestinian children be killed and injured, starved, and denied medical care, it has been challenging to know whether and how to engage with the young children in our lives about what is going on. As a Palestinian American elementary school teacher, I found myself unable to look at the 1st and 2nd graders in my classroom without seeing the faces of Gazan children of the same ages. This is a deeply painful time.

Many schools and educational institutions have adopted policies and practices that silence educators from talking about Palestine and Israel under threat of penalty or losing employment. Many adults have chosen not to have conversations with their children about Israel’s genocide in Gaza for fear that it will be too overwhelming or scary.

However, young children already hear about the genocide in Gaza or even see images of Gaza under siege that pervade social media and the news. Whether from the back seat of the car while a family member listens to the radio, overhearing grown-ups discussing the news in hushed tones from another room, attending a protest, or even hearing a friend make a reference at school, many young people already sense that something bad is happening in a place called Gaza.

For young children, and all of us, knowing something bad and scary is happening but not having the information they need to understand it generates fear and a feeling of being out of control. Giving children information they need to understand hard and scary events in developmentally appropriate ways supports them to feel agency and a sense of emotional safety.

Rather than remain silent when children have questions about Gaza, educators and caregivers of young children can give these young people tools to think critically about the world and take meaningful action to build a world where everyone has what they need to thrive.

It is not always possible to prepare for a conversation about a tricky topic with a young child. Sometimes a child makes a statement or brings up a question that requires immediate response. Remember, we can always say: “I want to think about how to answer that. Can we talk about this again later?” The most important thing is to show the child, with our words and our affect, that we are open to answering their questions.

Below are seven guidelines for conversations between adults and young children about Gaza.

1. Start with what they know. We can respond to a child’s question with another question. For example, if a child asks “Why are people bombing Gaza?” we might respond “I’m so glad you asked that question. What have you heard about what’s happening in Gaza?”

2. Listen and mirror the language the child is using. Children will use language that they can understand and process. It is the adult’s job to listen to the language children use as an indication of their developmental understanding. If a child says “They are hurting kids in Gaza,” we don’t need to use the word “kill.” Instead, we can mirror that language back: “Yes, the Israeli army is hurting kids in Gaza, and that is unfair and wrong.” If a child says “People in Gaza don’t have enough food,” we don’t need to use the word “starve.” Rather, we can build on this understanding: “Right, people in Gaza don’t have enough food to be healthy right now, because Israel is stopping more food from coming into Gaza.”

3. Use concrete, clear, direct language. Think about breaking big concepts into building blocks that the child can understand. Think about using words they already have references for. For example, young children will not understand the term “genocide,” but they can understand that “a group of people or an army are trying to hurt a lot of people from one place.”

4. Help the child differentiate their experience from the experience of people in Gaza. If the child asks “Will Israel bomb us here?” we might respond “No. That isn’t going to happen. Here we are safe from bombs. And we can work for a world where everyone is safe from bombs.”

5. Check in and affirm feelings (ours and the child’s). Conversations about violence and oppression are too often intellectualized by people not directly impacted. As adults, it’s our job to help children notice the feelings that come up and find ways to articulate and work with them. We can also be honest with the child about how we’re feeling. Children are often aware of our emotions even when we don’t name them. We can name our feelings directly in a way that does not put the child in a position of being our caretaker. For example, if a child asks “Do you feel sad about Gaza?” we might respond “Yeah, I do feel sad. I feel that in my heart. Where do you feel it in your body?” After the child responds we might affirm “Yeah, sometimes I feel it there too,” and ask “What are some things we can do when we feel sad?”

6. Make clear moral statements. It is OK, and important, to make clear moral statements about social issues. Young children are oriented to justice, and in a world pervasive with oppression it is important for adults to name it. We can make statements like “All people deserve to have food, water, and medicine” and “It is wrong to stop people from getting food.”

7. Give the child a way to take action. One of the most important elements of a conversation with a young child about hard truths is to offer them a sense of agency and opportunities for action. In my classroom, for example, I always pair conversations about climate change, a terrifying and inevitable issue, with lessons about climate justice organizing. Young children need to know there are ways to fight back against injustice in the world, and that they can participate in taking action. By offering them ways of taking action that bring them into the collective (e.g., making protest signs with friends or participating in a letter-writing day), we can use a moment of injustice as an opportunity to build solidarity and community. We can say “It’s our job to help change what’s happening in Gaza. Some ways we can do that are making art for the protest this weekend, or getting our friends to write letters to the people in charge of our country to tell them to stop sending weapons to Israel.”

* * *

Recently I was having coffee with an acquaintance who said about the genocide in Gaza, “I never imagined this would be happening.” I responded that, sadly, as a Palestinian American whose family has been impacted by Israel’s escalating military occupation of Palestine, I had known this was possible. However, what I never imagined I would see in my lifetime is the level of resistance and solidarity with the Palestinian people that has erupted in the United States and around the world since Oct. 7, 2023. I never imagined I would walk through the streets of my neighborhood in Philadelphia and see people sitting at coffee shops wearing keffiyehs or see so many Palestinian flags in the windows of my neighbors’ homes.

In such an unprecedented moment of resistance, we must take seriously the young people who will inherit the struggle for liberation. Giving young children language for understanding the truth about oppression, the tools to fight injustice, and the resources to build communities that can live in collective freedom is world-changing work. I invite you to imagine, when children across the world today are having these conversations and developing these tools and resources, what more liberatory futures could be possible.