Writing for Justice

Using Stories to Teach Solidarity

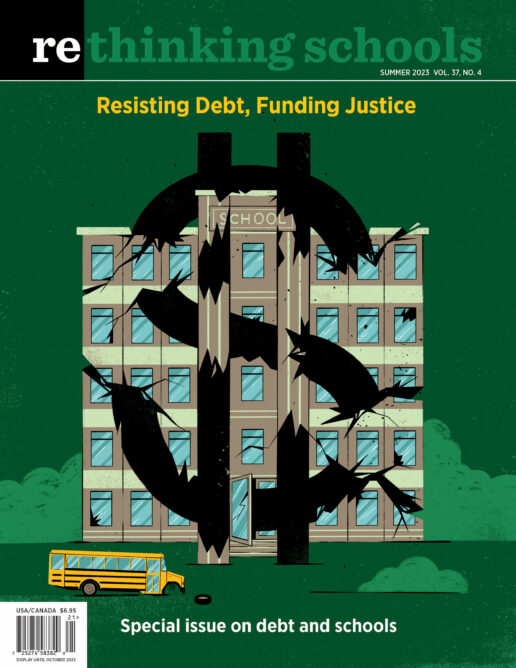

Illustrator: Amir Khadar

Acting in solidarity with others is a learned skill, but not one taught in most schools. I want students to understand that change doesn’t just happen; people work for change — fighting to end police violence, advocating for the rights of women and the LGBTQ community, stocking grocery shelves with produce from local farms, or creating schools where all students receive an engaging truth-telling curriculum. I designed this lesson to help students uncover those moments in their lives when they participated in an act of injustice, and then to use those narratives to rehearse acting in solidarity with others to change the situation. The lesson provides students an opportunity to see how history — and our lives — can change when we act in solidarity with others.

I have taught this narrative yearly with high school students, with teachers in the Oregon Writing Project Summer Institute, and in countless conferences and workshops. Over the years, the lesson has been used and repurposed for most grade levels and content areas. In every version of the lesson, I start with a piece of history or literature, then work with students to story their own lives. In previous iterations, we read excerpts from historical narratives, like James Farmer Jr.’s “On Cracking White City,” where he recounts integrating the Jack Spratt Coffee House in Chicago in 1941. When we read novels like Kindred or plays like A Raisin in the Sun, I ask students to list moments of conflict where justice could have happened.

Most recently, I used a chapter from Renée Watson’s novel Piecing Me Together with students at Jefferson High School in Portland, Oregon, in Dianne Leahy’s 9th-grade language arts class. Over the last two decades, Dianne and I have co-taught yearlong classes, developed new curriculum, and researched writing feedback strategies. She has graciously opened her doors to allow me to try out new ideas with her students.

Watson’s novels — every one of them — brim with love and joy, but also include moments of social reckoning where characters navigate injustices based on wealth inequality, race, weight, and gender. Often, these injustices parallel the daily abuses and exclusions that most students I work with also confront. In chapter 34 of Piecing Me Together, Jade, the main character, encounters racial profiling from a store clerk, discrimination against fat people, and the betrayal by her white friend, Sam. Watson, of course, resolves these issues later in the novel, but this short chapter provides a perfect platform for students to rehearse ways to talk back to injustice — through discussion and writing.

Reader’s Theater

Before launching into the story, I asked students, “Do you ever toss and turn at night wishing you could have a do-over? Maybe it was something you said or did or something you wish you said or did that you want to rewind and make right?” Most students nodded. One sat back in his chair and groaned. “Every day. Every night.”

“Me, too. Today we’re going to read a chapter from a novel where several people make mistakes that should keep them up at night.”

We read the story in reader’s theater style, with students taking the roles of narrator, Jade, Sam, the store clerk, and a woman shopper. Before we began, I asked them to think about the injustices in the chapter. “Keep these two questions in mind as we read: Who is harmed? How can the harm be repaired?”

After we read, I gave students time to write a response to my questions, then they shared their ideas with a partner. When we returned to the full group, students called out that the store clerk harmed Jade when she followed her around the store, telling her she couldn’t loiter, then asking for her purse so she could put it behind the counter. “Why is that a problem?” I asked.

Nadine’s hand shot up. “Jade is the only Black person in the store. The only one the clerk follows, and the only one whose purse she took. Yet she says it is store policy while all the white women got to keep their purses.”

“Is there anyone else who harms Jade?” This is a tricky part of the chapter, and one that plays out repeatedly when people of color explain a racist attack and their white friends, teachers, ministers don’t believe them or try to talk around it, explaining alternatives to the obvious racism at hand. Watson deftly portrays this behavior in the last scene of the chapter.

Almost before I could ask “How did Sam harm Jade?” Desiree jumped in. “Sam didn’t believe Jade. When a friend tells you something happened, listen. Believe them.” She looked at her white friend. “You wouldn’t do that to me.” Her friend agreed. Students took Sam’s racism seriously and called out how she wiped away the store clerk’s actions, dismissing Jade’s experiences and feelings.

Rewriting History/Literature

To help students explore ways to disrupt injustice, I ask them to rewrite Watson’s chapter. “Let’s talk about repairing the harm that happened. Who could have helped Jade? Think of all the characters in the story. Who could have stepped up? What could they have done? Talk to a partner and come up with as many ideas as you can.”

Partners assembled lists: Sam believes Jade. Jade demands to talk with the store manager. The woman who speaks to Jade at the end asks to speak to the manager. Sam returns the clothes in solidarity and takes Jade out for ice cream. Sam and Jade write a letter to the store and post it on social media. And then the key solidarity moment: All the women in the store either give their bags to the clerk or all pile up their purchases and ask for refunds.

“Let’s talk about repairing the harm. Who could have stepped up? What could they have done?“

After reviewing their delightful ideas, I set them to rewriting the chapter. “Start anywhere in the chapter. Include dialogue and details to put us in the story the same way Watson does.” As I roamed the room, I realized some students were writing summaries instead of storying their solution, so I quickly rewrote a section on the board to model what I wanted. Mitzi rewrote the final scene so that Sam becomes the friend that Jade needs after the confrontation with the salesclerk, using Jade’s interior monologue and narration:

Sam looks down at the two shopping bags full of clothes she just purchased. “It was all overpriced anyways,” she says, turning back to the store’s entrance. I watch in awe as Sam goes up to the return desk, pulling out every single thing she bought, demanding her money back. I see her talking to the customer service cashier as he scans her unwanted items. She must be explaining what happened to me because she looks mad. When she comes out, she gives me a big hug and suggests that we go get ice cream.

Perla’s revision allowed the white women a solidarity moment with Jade and Sam. What I like about this one is that in addition to the women and Sam intervening, Jade also speaks up for herself:

“It’s store policy,” the clerk says to me. I see a woman coming up to where the store clerk and I are standing.

“I have a bag. Why can’t she?” the older woman asks.

The clerk stutters, “Hers is quite large.”

More women interrupt. “I’ve come here with bags that same size and no one said anything to me,” one says.

I smile and say, “If you are not taking their bags, you’re not taking mine.” I look around and see Sam coming.

“What’s happening?” she asks.

I explain and we both leave the store with nothing but the manager’s contact information.

Reading Student Models

After rewriting a moment in literature, we read some of my previous students’ narratives to encourage conversations and memories. We chose stories that illustrated times young people stood up as well as times they didn’t. Some of the incidents take place in student homes, others in schools or on playgrounds. We also encouraged the class to think about how the piece was written — the use of dialogue, character and setting description, interior monologue. In my former student Sarah Stucki’s story “The Music Lesson,” Mr. Dunn, a music teacher, humiliates Mark for laughing out loud during class. Dunn forces Mark to come to the front of the choir and sing scales out loud by himself. Sarah wrote, “[Mark] was very embarrassed, and I didn’t blame him for crying. I would have too if Mr. Dunn had treated me like Mark, and I feel today that the only reason he was so mean to Mark was because Mark is Native American.”

Mark never returned to class — or to school — after that incident. And no one intervened. “The Music Lesson” provides a clear, accessible model that helps students remember those frozen moments when they observed a wrong, but looked away, not wanting to get involved. When I asked students to imagine a different ending to the story, one that kept Mark in the classroom and school, they returned to the solidarity moment and talked about how Mark’s classmates could have said they were laughing, taking the focus off Mark, or how they could have walked up and stood with Mark in front of the classroom.

We also read my student Josh Langworthy’s story “When I Was Young,” about the physical abuse in his home, and the time he fought back — first with a bat, then with a knife against his mother’s boyfriend who had been beating her. Josh’s mother takes the bat and the knife from him and orders him to leave the house. In this 9th-grade classroom, students argued about whether Josh made the right decision about how to intervene and suggested other methods that didn’t put his life or his mother’s in more danger.

Making Lists

Once students were steeped in stories, we began the process of probing their lives for incidents they might recount. “Sometimes we are targets of injustice as an individual,” I explained, “and other times we are targets because of our race, class, ethnicity, language, gender, immigration status, disability, or sexual orientation.” I started with times in my life to give them ideas and to demonstrate vulnerability.

The first episodes I described were typical and easy sibling stories that many students could relate to. I used specific details as I recounted how my older sister Tina forced me to go to the little store on the corner to buy her cigarettes and ice cream sandwiches. She wrote notes: “Please give Linda one pack of Marlboros” and signed my mother’s name. She also prefaced my errands with the statement “You best be making your break for the store before I . . .” I moved to another “family” story about the time my first husband beat me in front of the Catholic Church in downtown Eureka and no one stopped to intervene.

I tell this story every year because I want students to know it’s OK to write about stories that matter, to write about painful, personal topics. I was a battered woman who escaped one night after my husband beat me until he broke my nose, blackened my eyes, and tore out chunks of my hair. When he fell into a drunken sleep, I ran. I feared for the safety of my mother and the rest of my family, so I left my hometown the following day and found a new home and new life in Portland. I always tell this story because I want students to know that they can and should leave abusive situations. Many people have experienced abuse — sometimes personally, sometimes witnessing a family member. By sharing my experience, I acknowledge that abuse happens, that it’s not OK, and that it is possible to escape. Often my story opens the floodgates for students, like Josh, to share similar events. I distribute information about shelters for battered women and children.

Then I moved into stories that widened the frame of justice. I told, for example, how my 9th-grade teacher targeted me because of my class background when she made me stand and pronounce words and conjugate verbs as an example of how not to talk. Then she called on the girl whose parents owned most of the restaurants in town to demonstrate how to pronounce words and conjugate verbs correctly. While I shared moments from my life, I encouraged students to jot down ideas that my list sparked. This listing provided a way for them to get quiet, so they could collect their own memories. The prompt was simply: Write about a time when an injustice happened. You may have witnessed it, been involved in it as a participant, or you may have interrupted it.

I never rush this sharing or story-catching time because this narrative takes students to some of the most significant instances they will share during their classroom life. If I don’t allow adequate time to prepare students to engage seriously, and I don’t create a willingness to be open and take risks, students may never dare to write the honest stories that need to be written. Over the years I’ve discovered that students share based on their life histories, their own comfort with the class, and their willingness to talk about joyful and painful issues in their lives.

Let me pause. Some teachers might say this is “touchy-feely” stuff. Not rigorous. Not academic. Not part of school. I disagree. The best literature is the most honest; it doesn’t gloss over the hard parts. It’s why we love and hate Troy Maxson in August Wilson’s Fences. He isn’t nice. He’s been injured, and he strikes back at his wife, his friend, his sons. Honesty in writing is hard to come by, but when it comes, it should be celebrated. And we need to make room for this real work in the classroom.

Students listed, but they also chatted. The common phrase “I can’t think of anything” bounced around the room. As Dianne and I wandered, listening, asking questions, students started recalling stories. “Remember when the dance teacher made you stand out in the cold?” “What about the time our class made the substitute teacher cry?” First, the shared stories emerged, then the individual stories made their way onto papers. I collected their lists to share ideas the next day. As Dianne and I read these, we realized that some students had harassed their classmates — stories that could have caused more harm, as well as damaged the classroom community.

Dianne started class the next day by discussing a time when she allowed a student to share a story about an unkind action taken against a classmate. “This 9th grader was harmed twice — first by the incident, and second by telling the incident in class. Please do not share stories that will hurt a classmate.” After that caveat, we started by sharing an edited version of their lists, removing any that might have antagonized or hurt someone in class. We started with times they wished they had intervened:

Friends making fun of someone — online, in class, in hallway, to their face.

Friends targeting students with disabilities.

Classmates making a teacher cry.

A teacher making sexist/racist comments.

A woman calling a gas station attendant the “N-word.”

Friends stealing from a store.

Friends throwing things at a homeless person and calling them names.

Then we moved to times when they had stood up:

Spoke up to my counselor when I needed to transfer classes.

Stood up for my friend who was being bullied.

Stood up for someone about their sexuality.

Stopped friends from bullying a student with a disability.

Broke up a fight in the bathroom.

Sat by a girl crying on the stairs.

Stood up for my brother when my parents were picking on him.

After students located a story from their list or the collective list, I led them in a guided visualization. This strategy provides a passage from the classroom into their writing. I turned off the lights and asked students to close their eyes or put their head on the desk. Then I took them through the visualization: “Imagine you are both an actor in this movie in your head and a videographer. First, I want you to recall the scene where the story took place. Was it in a building? A home? Outside? What time of year? What was the weather like?” I timed one minute of silence for them to create mental images, then I moved on to characters. “Who was involved in the incident? Bring them into the space and recall details about them. Their actions. Their words. Nervous habits.” After another minute’s pause, I asked them to “put the movie in motion, so you can see, hear, and feel the memory unfold.”

Before I turned the lights on, I said, “Write in a whoosh to get the story down. We will revise in the days to come. Remember the stories we read: Use dialogue, setting, and character details.” I also encouraged them to use interior monologues as a way of telling how they felt during this act of injustice and whether they were changed by the events. Students wrote for about 20 minutes. We stopped five minutes before the class ended to have some students share a few paragraphs to help their classmates who might not have moved as easily into the writing.

On the follow-up revision day, I taught a lesson on character description — with excerpts from published novelists as well as former students: physical description, characterization through actions, dialogue, and setting. Movies, sitcoms, even novels, continue to use shorthand character descriptions — both for a laugh and for expediency. Students pick up on those. When Dianne and I scanned their character descriptions, we noticed stereotypical patterns — crooked teeth, big ears, etc. Their words provided an entrance into a discussion about the use of harmful descriptions that end up as a kind of bullying in a piece that is meant to disrupt injustice.

Read-Around

I opened the day of the read-around by talking about the importance of being present as classmates share their stories. As always, in every read-around, I asked students to take notes as people shared their narratives. “Today, your classmates are reading important stories from their lives. Some of these stories are painful. Some will be about times when they didn’t act, but wish they would have. Others will share about times they did act. Your job is to be hungry listeners. Be compassionate listeners. I want you to listen with your head and your heart. I want you to take notes on the topics, to note details that make the writing come to life, and to find honest feedback to share with each writer. I also want you to think about what conditions allowed people to act for justice, how people felt when they didn’t act.” If a student read a story where no one acted for justice in real life, we paused to figure out how they might act. These scenarios provided the class with opportunities to discuss how they can make a difference on their own.

Acting in Solidarity

After participating in this unit, two of my students told me about how they took these strategies to their choir class. According to Valentina, several girls had been laughing at a boy on the autism spectrum all year. Apparently, he flapped his arms in an odd manner when he sang. The girls mimicked his movements, laughing until they intentionally fell off the risers in escalating fits of laughter. Valentina and Desiree confronted the other girls on the boy’s behalf, telling them they didn’t find it humorous. They were worried that the girls would attack them, but after a brief exchange, the girls stopped harassing the boy. Other students discussed how they banded together to confront a teacher’s unfair grading practices.

Injustices haunted students long after the event, often remaining without resolution. One student wrote, “Looking back at the situation, I am very disappointed in myself that I did not confront the lady or even defend the gas station attendant. If I did that maybe the lady would have realized that what she said was wrong. Maybe that woman would have changed as a person.” Another student added a note at the end of her narrative: “I was disappointed that my friend was mistreated and I didn’t do anything, I was too distracted with my food to break it up. This feeling has been lingering with me for a long time and I wish I could go back and stop it.”

* * *

Social justice teaching is not putting a picket sign in students’ hands or printing signs against bullying to post in every classroom. Instead it is creating a community of conscience where injustice is made visible through students’ own lives, where writing moves from an assignment to an opportunity to tell a story that has sometimes lingered like an invisible scar. As they talk and listen to classmates’ narratives, students come to see each other more fully, as intellectuals, as collaborators in making a better world. They begin to learn that solidarity can be a way of life.