Women of the Day

Yuri Kochiyama

Recy Taylor

Sylvia Plath

Artemisia Gentileschi

Jeannette Rankin

Audre Lorde

In the 5th grade, I had to write a report on Abraham Lincoln. As I pored over my musty-scented, yellow-paged, cellophane-covered books from the Metropolitan Learning Center library, I became fascinated with Mary Todd. In fact, I spent so many words on Mary that I had to end my report before Abe even became president, hence my title: “Abraham Lincoln: The Early Years.” If you asked 5th-grade Ursula about this fascination, she might have said, “Mary was from a slave-owning family and yet her husband went on to free the slaves!” (Like most white American children, I was being miseducated about who freed the slaves.) Or I might have said, “She was crazy!” (Mental illness was a term I neither knew nor yet understood.) But today, 35 years on, I wonder if it wasn’t something else: Mary Todd was a woman.

Jeanne de Clisson

Hedy Lamarr

Viola Liuzzo

Helen Keller

Edith Windsor

Billie Jean King

Three years ago, Veronica Sackville-West, a quiet and brilliant sophomore U.S. history student, asked me if she could come in at lunch to talk about something. “Sure!” I answered, offering my standard response to the common student request for a little time to talk about anything ranging from grades to anxiety, classwork to family. When Veronica came in with two other classmates, Rachel Bard and Meg Smith, it turned out they wanted to talk about curriculum, and more precisely, about the lack of women they encountered in the pages of textbooks, classroom handouts, short stories, and novels. They were outraged and coming to me for advice about how to demand a change.

Fannie Lou Hamer

Joan of Arc

Carrie Nation

Misty Copeland

Marsha P. Johnson

Hannah Arendt

With some very light counsel from me, Veronica, Meg, and Rachel brainstormed two routes of activism. First, they considered lobbying for a district-wide inventory of women in the curriculum. The study would provide the data to demand more novels by and about women, more attention to women in history and science, more representation at all levels. While I loved this idea — its attention to how women are systematically underrepresented — I cautioned the students that this would be a slow-moving effort, unlikely to reap any tangible rewards while they were still at the school. Perhaps that is what led them to embrace the second route: a stand-alone course. I shared with them that Gender Studies was already approved by the board, an elective that had been taught for a few years before it fell out of rotation. I explained that if they wanted to advocate for the return of this course it would be relatively straightforward since there would be no need to go to the board. No, they said, Gender Studies isn’t what they wanted. They wanted Women’s Studies, a class that would be not just about social constructions of gender and identity, but also about women — their lives, histories, existence.

Sue Kunitomi Embrey

Sister Helen Prejean

Sarah Kay

Anita Hill

Lin Farley

The next year, as juniors, Meg, Rachel, and Veronica borrowed dozens of books from me, scoured university websites for course descriptions and reading lists, collected articles and slowly, methodically, built a course description that read, in part:

The course will study women’s contributions to history, civics, and the arts. In addition, it will examine how women’s historical experiences differ for individuals of different backgrounds, analyzing how race, ethnicity, class, sexual orientation, and gender nonconformity intersect with the overall concept of feminism.

With that in hand, along with their personal stories of educational alienation in the face of a curriculum reinforcing the invisibility and unimportance of women, the three young women headed to the school board, which approved the course. Laura Paxson Kluthe, longtime history teacher, agreed to teach it in its first year. She and the girls spent the rest of the year writing the syllabus for “Introduction to Women’s Studies,” which would be offered for the first time during the girls’ senior year.

Sarah Silverman

Kakenya Ntaiya

Wu Zetian

Lauren Cook

Janet Mock

Kathy Jetil-Kijiner

When Ms. Paxson Kluthe announced her retirement, I pounced on the opportunity to teach Women’s Studies in its second year. As I dove into building units (gender and identity, gender and work, women in politics, etc.), I realized I wanted to add something else, something that would pay homage to the student founders’ original and most central concern: pure representation.

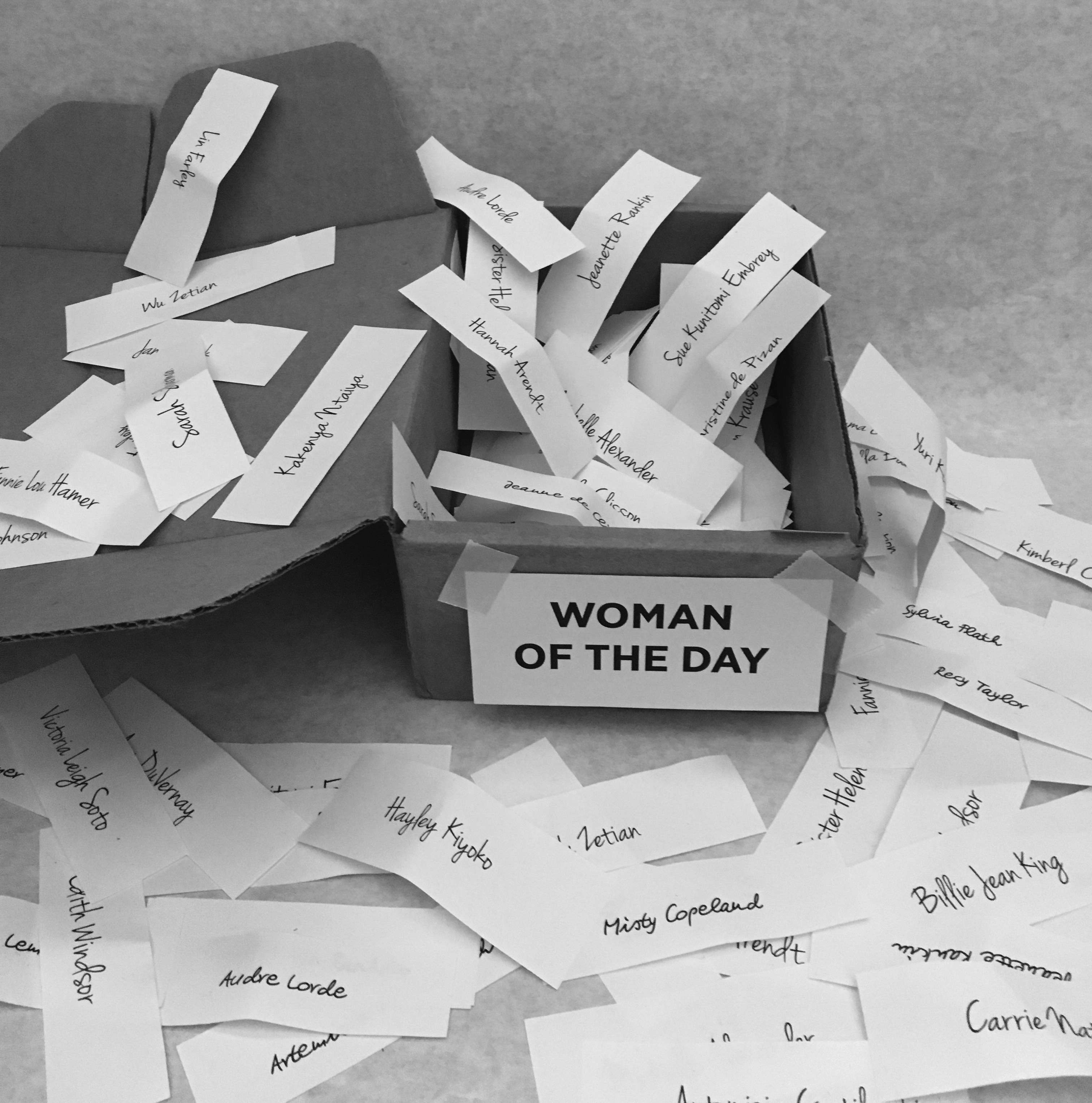

I decided each class would start with a Woman of the Day. I imagined quick introductions to a compelling and wide variety of women. About half of the women of the day were selected and presented by me, the other half by students. My only instruction to students was: Choose a woman of historical, social, political, economic, environmental, legal, artistic, religious, scientific, or personal interest. She can be from any place or time. Sometimes we watched a short YouTube clip of or about them; sometimes we read and discussed an excerpt of their work. It was basic direct instruction; nothing fancy. But as the year progressed, as my students and I felt the accumulating weight of the names and lives of the women we recognized, invoked, and honored, I couldn’t help but wonder if this simple daily ritual turned out the be the most important teaching choice I made all year.

Ella Baker

Lucretia Mott

Nikki Giovanni

Virginia Woolf

Clara Lemlich

Victoria Leigh Soto

Yes, I spent way more effort on our detailed unit on the gender wage gap, was far more careful in my curriculum on #MeToo, and spent more time orchestrating our rich reading and analysis of The Color Purple, but each of those units was in some way recognizable and familiar. The piling up of these women — so many women, day after day — was somehow more radical, more unexpectedly powerful.

Shirley Chisholm

Queen Lili’uokalani

Courtney Love

Angelina Grimk

Ava DuVernay

Celia (from the 1855 case State of Missouri v. Celia, a Slave)

It was the unexpected excitement of students like Senna, a nonbinary junior, who exclaimed after learning about Carrie Nation, “Oh my God, I love her! We just finished learning about the temperance movement in AP U.S. History and she wasn’t even mentioned. I am definitely putting her badass hatchet in my presentation next week.” It was the joy of serendipitous connections, like when you learn a new word and suddenly start hearing it everywhere. One day Angela, a soccer-playing senior, asked if she could make an announcement at the start of class, explaining, “You guys, do you remember when we learned about Marsha Johnson, the LGBTQ activist from the Stonewall riots? Well, I stumbled across a documentary about her on Netflix this weekend. It. Was. So. Good. I definitely recommend it.” It was the way we all started to notice more women who . . . well, needed to be noticed.

In my U.S. history class, I was teaching about Hawai’i and Emily said, “Ms. Wolfe, Queen Lili’uokalani should be one of our Women of the Day!” Even folks not in the class would offer ideas. I put a little box at the front of my room with note cards and invited anyone to contribute. I received suggestions from students, teachers, secretaries, and educational assistants. Go figure. There is a bottomless reservoir of women who matter, deserve attention, and who do not regularly show up in our classrooms and curriculum.

Emma Goldman

Hayley Kiyoko

Kimberlé Crenshaw

Christine de Pizan

Dolores Huerta

Woman of the Day is not the most creative teaching idea I have ever had, but it may be the most transformative in heightening my awareness of the paucity of women across the curriculum, even in my own U.S. history classes. The trick now will be to transfer the lens from Women’s Studies to other contexts, making sure there is a diverse array of women — not just cisgender white women — showing up in my curriculum, in my writing, in the articles and tweets I share online, in my daily references to popular culture, literature, and politics.

Right now 90 percent of Wikipedia editors are men, more than 75 percent of congressional seats are held by men, and more than 90 percent of the directors of top Hollywood films are men. If I do not use my classroom to proactively resist the overrepresentation of males in our dominant discourse, I will condemn another generation of students to sit in classes empty of women’s lives, voices, and vision. Thanks to my students — Veronica, Rachel, and Meg — that is no longer my fate.

Joy Harjo

Callie House

Michelle Alexander

Maya Lin

Allison Krause

and yes,

Mary Todd