Why We Should Teach the History of the Black Panther Party

On Sept. 28, 2020, the Oakland City Council convened to discuss a resolution pertaining to the legacy of the Black Panther Party (BPP), which had been founded in Oakland more than 50 years prior. That evening, the members discussed whether or not to “approve plans to install a memorial to Huey P. Newton and the Black Panther Party outside the Alameda County Courthouse” and to use “the iconic photograph of Huey Newton seated in a wicker chair with a rifle in one hand and a spear” as the basis for the memorial.

The council members engaged in a lively debate as to the significance of the BPP — was it armed struggle, community programs, or something else? One council member passionately argued against using funds for a statue and instead proposed that the city establish “a fund, named for the Panthers, to support the types of programs . . . that they put into practice.” Another took issue with having a single person represent the BPP and urged members to “return this monument proposal to the people by creating an open call for Black artists to submit proposals for a new monument concept, one dedicated not to the image of a single man, but to the legacy of the Black Panther Party as a party of the people . . . ”

It was another controversial meeting of the Oakland City Council with one important distinction — the “council members” were actually preservice teachers in a History Methods class at UC Berkeley. My co-teacher Lizzie Humphries and I had created this city council simulation as the culmination of a three-day unit on the BPP. The activity was an example of our students’ major fall semester assignment — a weeklong curricular unit of instruction that they would plan and teach as student teachers. Our students come from a variety of racial and class backgrounds and are drawn to UC Berkeley’s program because of its explicit focus on social justice. Over the past three years, they collectively have identified three key qualities that make the Black Panther Party unit their favorite: asking questions that matter, engaging critically with diverse sources, and making arguments to stakeholders.

Ask Questions that Matter

Social studies instruction needs to move away from a static model in which students learn by memorizing the “truth” posited in textbooks to a dynamic approach in which they ask questions, gather and analyze evidence, and make arguments about the past.

Our unit about the Black Panther Party sought to expose our students to an essential history that originated powerfully in the same city where many were now student teaching and to do so in an open-ended way that allowed them to draw their own conclusions. Our compelling question was “How should the City of Oakland better memorialize the multifaceted legacy of the Black Panther Party?”

When we began three years ago, the only visible memorial to the Black Panther Party in Oakland was a makeshift sign attached to the pole of a streetlight at 55th Street and Market, indicating that the BPP organized to have this streetlight installed after a car struck a child at the intersection. In the two years since we started teaching this unit, there has been growing attention to the BPP’s legacy in its birthplace of Oakland. The City Council renamed a section of 9th Street as Huey P. Newton Way in honor of the leader and to mark where he was killed. Nearby, a bronze bust of Newton was installed to memorialize his critical role as co-founder along with Bobby Seale. And in the spirit of self-determination that infused the more than 60 BPP Community Survival Programs, local West Oakland resident Jilchristina Vest turned her home into a mural to honor BPP women. And the recently published book Comrade Sisters by longtime Panther Ericka Huggins with photographs by Stephen Shames further illuminates the experiences and vital role of women in the BPP.

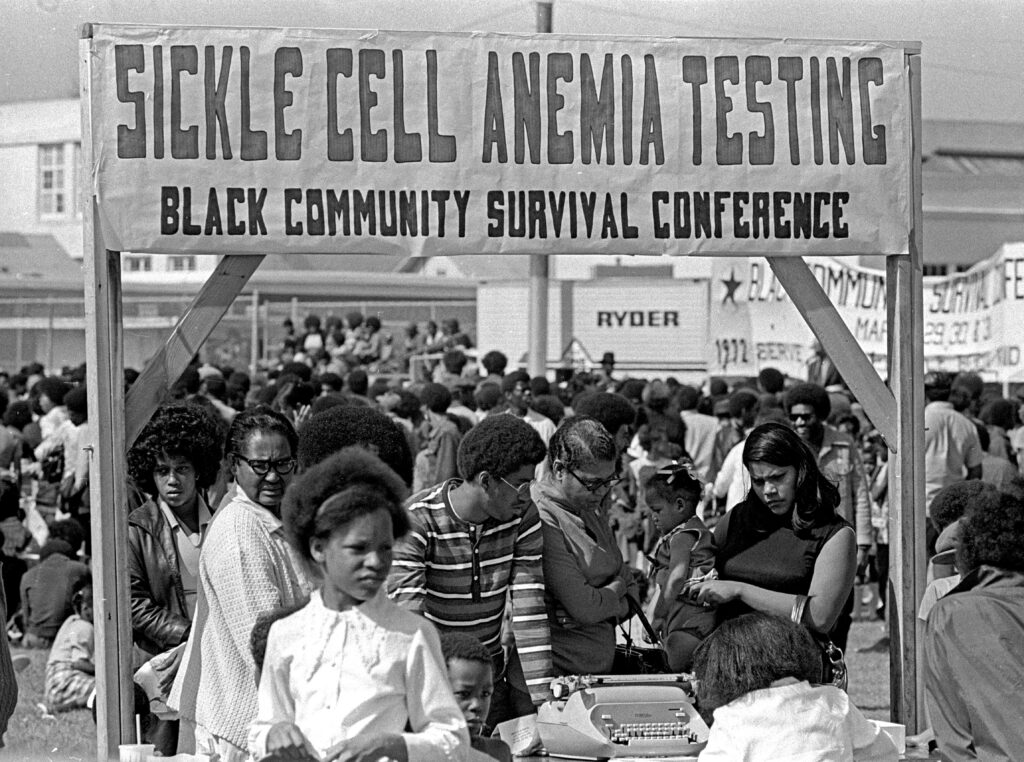

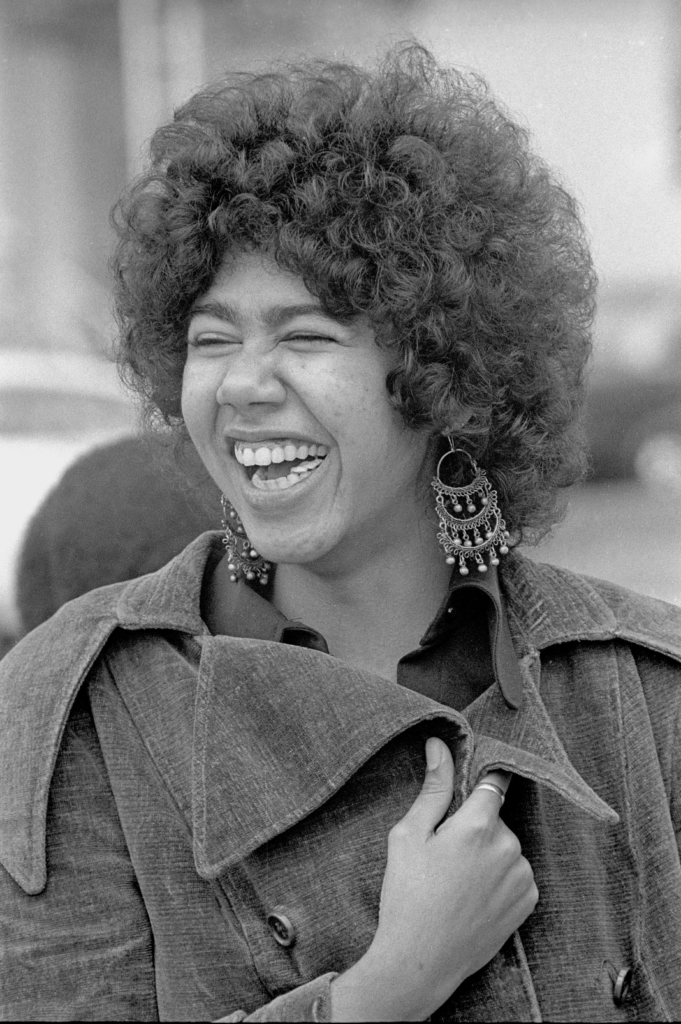

Ericka Huggins at the Black Community Survival Conference, March 30, 1972.

By asking our students to investigate the BPP’s impact, we ask them to participate in a vibrant and vital dialogue as to how to memorialize the past, make sense of our present, and envision a more just future. Variations of our compelling question could be used in different regions of the country, such as, “How should the City of X memorialize the Black Panther Party’s legacy in that city?” Further still, students can investigate any significant history that has not been memorialized — which, given our country’s tendency to commemorate wealthy, white leaders, would include many contributions, stories, and struggles of people of color, women, transgender people, and the working class. For example, educators in New York City could ask, “How should the city remember the largest civil rights protest in U.S. history, in which nearly 500,000 students stayed home to protest the quality of education for Black and Puerto Rican students?” Teachers in Louisiana could ask, “How should the state remember the uprising of 1811, in which enslaved people armed themselves to fight for their freedom?”

Engage Critically with Diverse Sources

In our unit, we wanted to introduce evidence to invite controversy and complexity about the BPP. For our first step, we started with two opposing secondary sources — Black Against Empire by Joshua Bloom and Waldo E. Martin Jr. and a critique of the book by Steve Wasserman in The Nation. These readings were challenging for our graduate students, so a different set of texts that disagree with one another on the legacy of the BPP would be necessary for the K–12 context.

To get a flavor of Wasserman’s critique, here is one of his points: “Bloom and Martin barely concern themselves with the party’s swift descent into thuggery, consigning only six paragraphs in the closing pages of their book to a section called ‘Unraveling.’ They prefer to dwell on the party’s glory years from 1967 through 1971.” We asked students to discuss “What behaviors or images come to mind when you read the word ‘thuggery’? What does the choice of this word suggest about Wasserman’s perspective/beliefs?”

At the end of that class, we summarized the position of each reading and connected back to our unit question. “What would Wasserman say is the legacy of the Black Panther Party?” we asked. “What would Bloom and Martin say is the legacy of the Black Panther Party?” Derrick, who often provided thought-provoking perspectives, shared that Wasserman would likely say that “violence” was part of the BPP’s legacy. Another student, Grace, had lived abroad and held an international perspective on movement building. They suggested that Bloom and Martin believed that the legacy of the BPP is its anti-imperialist stance in building cross-racial solidarity with groups who opposed the Vietnam War. Even from this unit’s first day, students saw that there was not just one way to think about the legacy of the BPP.

Free grocery distribution at the Black Community Survival Conference.

In our next class, we introduced evidence that further complicated the BPP’s legacy. Students looked at excerpts taken directly from the Black Panther Community News Service, which at its height had a weekly distribution of more than 300,000 copies. They read about the community survival programs like the “Free Breakfast Program,” the “Free Busing to Prisons Program,” and the “Free Ambulance Service”; they learned about the pedagogical approach of the Oakland Community School, open from 1973 to 1982; and they saw photographs of Bobby Seale and Elaine Brown announcing their campaigns for mayor and City Council in Oakland. Based on these sources, Maya, a student who grew up in the Bay Area, pointed out that “perhaps no program was more important or famous than the BPP’s Free Breakfast for School Children Program, which pushed the U.S. government to increase funding for federal lunch programs in schools.”

For the second hour of class, we were joined on videoconference by Ericka Huggins, the former director of the Oakland Community School. Students developed questions related to the BPP’s legacy, including:

- How has your perspective changed over the years regarding your vision of what the BPP originally stood for and what it means to you today?

- How do you see the impacts, particularly the educational impacts, of the Black Panther Party within the Bay Area today?

- In your life, have you seen progress around racial justice? Or have we stayed still?

Huggins spoke powerfully about her experiences in the BPP and as the director of the Oakland Community School. Afterward, in a shared document, our students recorded ideas about the BPP’s legacy:

- “The BPP holds a legacy of enduring hope and courage through community aid and a humanist philosophy.”

- “Ericka seemed to emphasize the role of women in, for example, community survival programs and membership, pretty often, so I assume that she would want the contributions of women to be included in the legacy of the party.”

Many original members of the BPP have passed, but there are still many alive who have vivid memories. The time is now to invite these elders to speak to students. The BPP had chapters in dozens of cities, and organizations like the Black Panther Party Alumni Legacy Network can help connect educators with BPP members in cities like Kansas City, Seattle, Chicago, and Philadelphia. As Natalia wrote, “It was really amazing to see history come to life, and this is something that I want to strive for with my students: finding ways to make history tangible.”

Inspired by Ericka Huggins, our students brought their enthusiasm to the culminating task of constructing an evidence-based argument. They had encountered four different sources that approached the BPP’s legacy from a different perspective — Wasserman, Bloom and Martin, excerpts from the Black Panther Community News Service, and their interview with Huggins. As a next step, my co-teacher Lizzie and I wanted students to turn their ideas about the BPP’s legacy into an argument about how Oakland should memorialize the party.

Make Arguments to an Audience

During the first two years, we had them make oral arguments on a hypothetical resolution as if they were Oakland City Council members. We decided to change this approach due to two limitations: one, the City Council had recently approved the installation of a Huey P. Newton memorial, which made our hypothetical resolution out of date; and two, the resolution limited how our students thought about the legacy because it set up a binary: They were either for or against the resolution. This year, we wanted to encourage a wide range of arguments about the BPP’s legacy and how it should be memorialized. We asked students to “choose a specific elected official and write an advocacy letter” in which they “propose a memorial addressing elements such as the location of the memorial, subject and form of the memorial, what perspective(s) you seek to represent, and the process by which the memorial will be created.”

On the third day, we set out to help them arrive at a claim and start outlining arguments. Given the power of the interview with Ericka Huggins, we knew that they might be swayed to take her position, so Lizzie and I created a table summarizing what each source might say about the BPP’s legacy based on notes from prior discussions in class. We had students read the summaries, add their ideas, and then draft claims that they could support with evidence. They wrote these initial claims on Post-its, so that we could put them on the wall and look at the themes that emerged. These included:

- Schools/education

- Community aid

- General impact

- Community action/self-determination

- Global/international solidarity

We also provided an example of an advocacy letter and a graphic organizer that provided prompts for each paragraph (see Resources). For example, one prompt reads “Personalize the issue and explain how it affects your life. Describe an experience, lived or witnessed, that has led you to this position.”

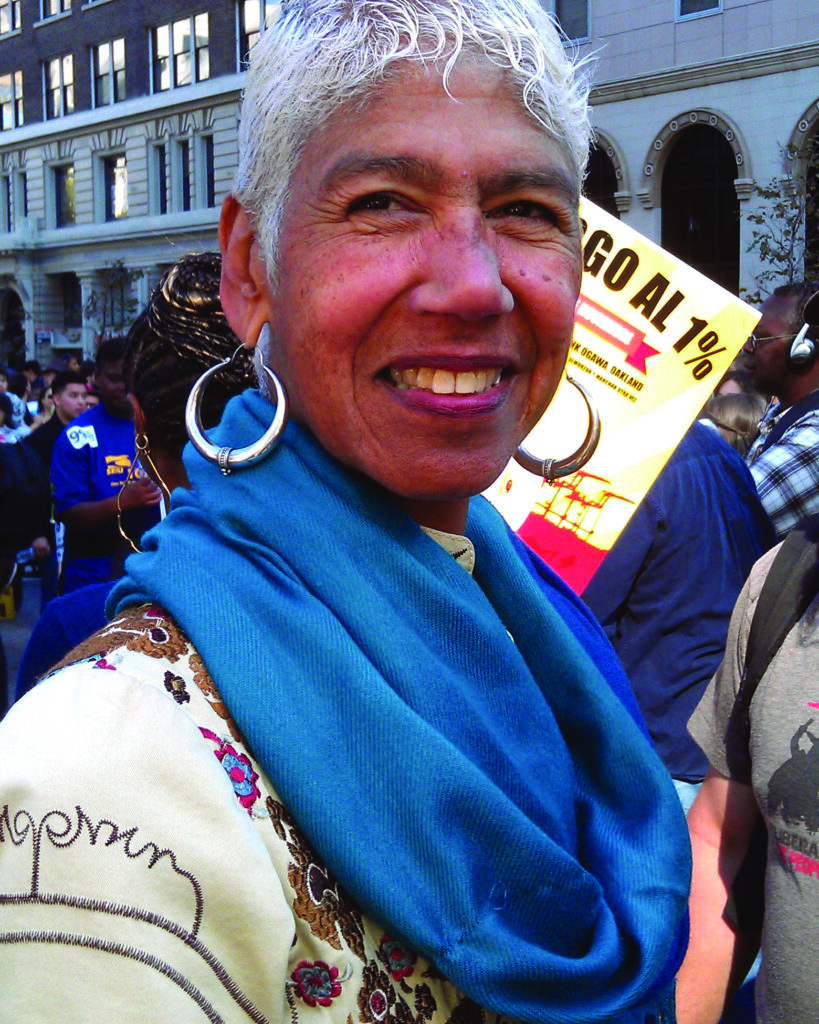

Ericka Huggins in 2011.

Between the third and fourth class, our students created an initial draft of their advocacy letters. In class, we grouped them into trios and asked each student to share their letter aloud and the other two to listen for ideas of how to strengthen their own letters. After getting a sense of how their peers had approached the assignment, we gave them time to revise and then each student chose three sentences from their letters to read aloud. In sharing and listening, students saw that even though they started with the same historical evidence, they arrived at different conclusions.

Here are a few excerpts, each addressed to then-Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf:

From Alex: “As a concerned citizen and student of history, I am calling on your office to memorialize the housing efforts of the Black Panther Party (BPP) by seeing to the construction of affordable housing units in Oakland. As you are aware, the Black Panther Party fought tirelessly for decent housing for people in Oakland, and particularly for the Black folks who inherited the legacies of structural racism and housing discrimination across the United States . . .”

From Martin: “The City should create a multicultural memorial that commemorates the international historical impact and influence of the Black Panther Party. This would foster local leadership in the future with an eye toward global responsibility and influence, stemming from the actions and movements established by the Black Panther Party.”

From Michelle: “This proposition is about keeping the spirit and values of the Black Panther Party alive in our community to prioritize survival, healing, and joy for the next generation. . . . The core of the Black Panther Party’s legacy lies in the community programs and models for community aid that they established through their Program for Survival (detailed in the March 1973 issue of their newspaper). . . . We have the opportunity to realize this part of their vision today through the creation of a comprehensive health education program in the name of the Black Panther Party that focuses on educating community members about the racialized history of health care and the current resources available to them, including both mental and physical health services.”

Going Forward

We wanted our students to not only see but also to feel how the parts of this unit — the compelling question on a topic of significance to the present day, the intellectual practice of engaging with evidence and perspective, and the performance task of writing for an authentic audience — came together. To our delight, the various perspectives argued in our students’ work were based in historical evidence, informed by class discussions, and ultimately expressed in students’ unique voices.

We ended the unit buzzing with ideas for how to make it better next time. We realized too late that we had not figured out how our students could take action with their advocacy letters. They needed more time to revise their letters, and with more polished writing, we could have had students vote on a letter that they wanted to sign in the form of a petition and send to a stakeholder (e.g., Mayor Libby Schaaf). Or we could have had students send their individual letters to the various elected and appointed leaders.

The Black Panther Party had an encompassing and captivating ideology, and its members took bold action to serve the people. Despite its short life, it has had widespread impact. When we ask students to grapple with the question of the legacy of the BPP and the legacies of other social justice movements, we engage them in unresolved issues of the past and we ask them to envision and act toward the kind of future that they want for all children.

Resources

The example advocacy letter can be found here: bit.ly/3lkSa7N

The advocacy letter graphic organizer can be found here: bit.ly/3Fst1iv