What’s Missing in Holocaust Education?

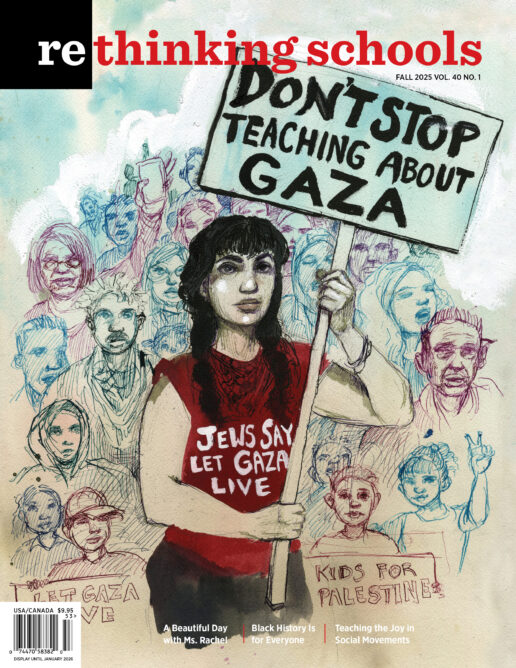

Illustrator: Olivia Wise

After the Nazis invaded Poland in 1939, Genya Gelbart and Henryk Kowalski were pushed out of their homes into ghettos, forced from the ghettos to slave labor camps, and lost most of their family by the time they escaped to Sweden in 1945. Genya and Henryk married and immigrated to Israel in early 1949. But when they arrived at the house the Jewish Agency had provided them, they noticed table settings in the yard and realized the former Palestinian inhabitants had quickly fled the home Genya and Henryk were supposed to occupy.

“It reminded us how we had to leave the house and everything behind when the Germans arrived and threw us into the ghetto,” Genya explained in a video testimony recorded by her daughter. “And here it was just the same situation, and it was not in us to stay. I did not want to do the same thing the Germans did. We left . . .”

Genya and Henryk’s story was detailed by Alon Confino, an Israeli historian who worked as the director of the Institute for Holocaust, Genocide and Memory Studies at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Confino’s essay appears in The Holocaust and the Nakba: A New Grammar of Trauma and History, a compendium of articles by Arab and Jewish scholars who examine two examples of ethnic cleansing: Nazi Germany’s extermination and displacement of 6 million Jews — and the Zionist expulsion of 750,000 Palestinians during the 1948 Nakba (Arabic for “catastrophe”).

The Kowalskis’ story and Confino’s depiction are part of a tradition among both Holocaust survivors and Holocaust and genocide studies scholars who argue that the Holocaust’s primary lesson is best summed up in the phrase “Never Again for Anyone” — and insist on a comparative approach to the Holocaust that includes Palestinian oppression.

And yet the common approach in K–12 Holocaust education is to teach the Holocaust as an isolated and unique horror. Students in middle or high school are generally not taught the nightmare that followed the immigration of Jewish refugees to Palestine, where Zionist militias massacred Palestinians, burned their olive trees, and erased Arabic names from streets and towns. The failure to teach the trauma of Palestinian displacement and dispossession sanitizes the violent establishment of a Jewish state on Palestinian graves and erases Jewish voices of resistance to the colonization of Palestine. In a comparative curriculum, students could learn of the cycle of abuse — Germany exterminating Jews, Zionist militias slaughtering Palestinians — and the inherent danger in a state defined by ethnic superiority.

Instead, pro-Israel organizations push for a curriculum that exploits the trauma of Nazi concentration camps to pronounce Israel as the only safe harbor for Jews. “Implicit in this renewed campaign for Holocaust education is an attempt to silence Israel’s critics by branding them antisemitic, cutting off their employment and leading others to self-censor for fear of unfounded accusations,” observes Seth Morrison, board member of Jewish Voice for Peace Action.

Echoes & Reflections Echoes the Israel Lobby

Twenty-nine states require Holocaust education. The vast majority have added or strengthened these requirements in the last five years. The biggest state requiring Holocaust education is California, so what occurs there has national implications. In 2024, the Jewish Public Affairs Committee (JPAC) and the California Legislative Jewish Caucus lobbied the state to launch the “California Teachers Collaborative on Holocaust and Genocide Education” to provide professional development for teachers. Although the 14-partner alliance includes scholars on Cambodian, Armenian, Guatemalan, Rwandan, and Native American genocides, most organizations are Holocaust-centered and five are explicitly Zionist. Missing are Palestinian scholars and experts on what human rights groups describe as Israel’s present-day genocide in Gaza. The absence of Palestinians raises the question: What is the point of genocide education if not to stop current genocides?

The collaborative recommends educators adopt Echoes & Reflections, a 12-unit curriculum co-constructed by the Anti-Defamation League, Yad Vashem, and the Shoah Foundation, all of which offer unconditional support for Israel. The Echoes & Reflections website boasts that it has been used by “more than 168,000 educators, reaching an estimated 10 million students” since 2005. The curriculum on the Holocaust features lesson plans incorporating primary and secondary sources, video testimonials, and podcasts. The first 10 units focused on the Holocaust encourage students to study the rise of the Nazi Party and how Jews maintained their humanity and resisted German fascism. The problematic nature of the curriculum becomes clear as it asks students to draw lessons about today from what they’ve learned about the Holocaust.

Unit 11 on contemporary antisemitism is often marketed as a stand-alone unit, which the Shoah Foundation claims is one of its “most-used resources.” The unit conflates antisemitism with anti-Zionism. Indeed, one unit objective asserts that students will “identify current features of antisemitism including Holocaust denial and distortion, and demonization of Israel.”

Equating Judaism and Zionism

The first lesson begins by asking students to fill out a graphic organizer (“Who Are the Jewish People?”) in which “connection to Israel” is pulled out as a key aspect of Jewish identity. Students watch a slick introductory video, “What Does It Mean to Be Jewish?” A young woman retrieves artifacts — the Old Testament, a Kiddush wine cup, the Dead Sea Scrolls — while escorting the viewer through Abraham’s belief in monotheism, Jewish enslavement in Egypt, the Jews’ “2,000-year exile” from the land of Israel — and ultimately concludes that “the yearning to return to our biblical homeland has been the deep and emotional heart of Jewish life.”

Yet fewer than half of the world’s 15.7 million Jews live in Israel. Nevertheless, the idea that Zionism has always been an integral part of Judaism is reinforced by the next student handout, “A Brief History of Israel.” It begins:

The history of the Jewish people and their roots in the Land of Israel span 3,500 years. It was here that the culture and religious identity of the Jewish people was formed. Their history and presence in this land has been continuous through the centuries, even as the majority of Jews were forced into exile almost 2,000 years ago. . . . Throughout these 2,000 years, most Jews who were in exile, regardless of their country of residence, continued to view a return to their ancient homeland as an essential part of their identity and a source of hope.

This narrative establishes Jews as indigenous to Palestine and hammers home the idea that Zionism has been an essential part of Jewish identity.

In 2020, a Pew Research poll found that nearly one in six Jews believe that caring about Israel is not important to what being Jewish means to them. That number increases to one in four amongst Jews under 30, and one in three amongst secular Jews.

Although there have always been Jews in Palestine, prior to the 19th-century Zionist movement, these Arabic-speaking Jews constituted 2 to 5 percent of the Palestinian population. It wasn’t until the 1880s, when a wave of violent pogroms (anti-Jewish riots) swept across the Russian empire, that Zionism grew in popularity — but remained a minority position amongst Jews around the world. In 1885, when nearly all U.S. synagogues identified as Reform, Reform Judaism rejected Zionism, proclaiming, “We consider ourselves no longer a nation, but a religious community; and we therefore expect neither a return to Palestine . . . nor the restoration of any of the laws concerning a Jewish state.”

And while after the Holocaust — and especially after the 1967 and 1973 Arab Israeli wars — there was growing sympathy and identification toward Israel amongst U.S. Jews, non-Zionism and anti-Zionism remained major currents of U.S. Jewish opinion well into the 1970s (see resources). Even today, a significant minority of Jews continue to reject that Israel is a central part of their Jewish identity. In 2020, a Pew Research poll found that nearly one in six Jews believe that caring about Israel is not important to what being Jewish means to them. That number increases to one in four amongst Jews under 30, and one in three amongst secular Jews.

Erasing Palestinians and Ignoring the Colonial Nature of Zionism

“A Brief History of Israel” sanitizes the colonial nature of Zionism. “The Zionists,” the authors write, “promoted increased Jewish immigration to Palestine and . . . sought international recognition of the Jewish right to independence in Palestine.” But what “right” did Jews who were immigrating to Palestine have to claim the land of the people living there?

The handout portrays Palestinian efforts to resist colonization as irrational hatred: “The Arab population strongly opposed the Jewish return to the area and rejected the idea of an independent Jewish state. Thus, the Arab desire for independence clashed with the Jewish desire for return.”

But as Israeli historian Ilan Pappé writes, “The diaries of the early Zionists tell a different story. They are full of anecdotes revealing how the settlers were well received by the Palestinians, who offered them shelter and in many cases taught them how to cultivate land. Only when it became clear that the settlers had not come to live alongside the native population, but in place of it, did the Palestinian resistance begin.”

The handout blames Palestinians, ignoring the context that could explain their actions. When it discusses the 1947 U.N. partition plan that divided Palestine into Jewish and Arab countries, it fails to mention that Jews were only one-third of the population; even the state earmarked for Jews would have been almost half Palestinian. They paint a picture of Jews as reasonable, and Arabs as aggressors: “The Jewish leadership in Palestine accepted the U.N. plan for the establishment of two states. . . . However, the leadership of the Palestinian Arabs and the surrounding Arab states rejected the plan and almost immediately began to attack the Jewish areas.”

Echoes & Reflections erases the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians between 1947 and 1949, a plan enacted by Zionist militias that destroyed more than 500 Palestinian villages, demolishing homes and massacring villagers. All to rebrand the land a Jewish state. As Pappé writes, “Military orders were dispatched to units on the ground to prepare for the systematic expulsion of Palestinians from vast areas of the country. The orders came with a detailed description of the methods to be used to forcibly evict the people: large-scale intimidation; laying siege to and bombarding villages and population centers; setting fire to homes, properties, and goods; expelling residents; demolishing homes; and, finally planting mines in the rubble to prevent the expelled inhabitants from returning.”

Instead, this history is presented through passive voice: “As a result of the fighting, between 700,000–750,000 Arab residents were displaced and became refugees.” This is followed by a sentence that justifies the forced expulsion of Palestinian residents by comparing it to the mostly voluntary emigration of Jews — actively encouraged by Israel — from Arab countries in the wake of Israel’s declaration of nationhood.

The student material erases Palestinian suffering, characterizing conflicts since 1948 as “spurred by tensions over borders, security, and land disputes.” Echoes & Reflections fails to mention that Israel has illegally occupied the West Bank and Gaza since 1967. But it blames Arabs and Palestinians for the failure of peace efforts. After detailing multiple Israeli “attempts to achieve peace” the handout concludes “Despite these efforts of peace, in most of the Arab and Muslim world, there continues to be a great deal of opposition to Israel’s right to exist.”

But as Francesca Albanese, U.N. rapporteur for Occupied Palestine, explained, “Israel does exist. Israel is a recognized member of the United Nations. Besides this, there is not such a thing in international law like ‘the right of a state to exist.’ . . . What is enshrined in international law is the right of a people to exist.”

After the brief history, Echoes & Reflections leads students to the conclusion that “Israel is a democratic republic. . . . Like other democratic, multi-ethnic countries, Israel struggles with various social and religious issues and economic problems.” But 4.5 million Palestinians live under Israeli occupation, are barred from voting in national elections, and must contend with threats of home demolitions, checkpoints, indefinite detention, and torture. Yet the word “occupation” doesn’t appear once in the four-page handout.

Taking on Today’s Palestinian Liberation Movement

One handout instructs students to conclude that critics of Israel are antisemitic: “Anti-Zionism as a Vehicle to Promote Antisemitism.” The authors police criticism of Israel to condemn those who “cross the line” into “denigration that can be considered antisemitic.” Students are encouraged to use “the three D’s test” to determine whether speech reflects “demonization” of Israel to blow out of proportion Israel’s actions; “double standards” to single out Israel for criticism despite other countries’ human rights violations; and “delegitimization” to deny Israel’s “fundamental right to exist” as a Jewish-defined state.

Anti-Zionists criticize Israel’s maintenance of Jewish supremacy inside its 1967 borders, where one-fifth of the population is Palestinian living as second-class citizens. Anti-Zionists denounce Israel’s subjugation of Palestinians in Israel’s occupied territories, who are barred from voting in Israel’s national elections though they make up roughly half the population under Israeli control.

“In fact, growing numbers of Jews and others identify as anti-Zionists for legitimate ideological reasons,” writes Rabbi Brant Rosen in a 2016 op-ed published in Haaretz. “Many profess anti-Zionism because they do not believe Israel can be both a Jewish and democratic state. Some don’t believe that the identity of a nation should be dependent upon the demographic majority of one people over another. Others choose not to put this highly militarized ethnic nation-state at the center of their Jewish identity.”

“The purpose of the three D’s test is not to stem antisemitic hate but to suppress debate on Israel’s decades-long occupations and genocide in Gaza,” stated attorney Robert Jereski, who heads CODEPINK’s U.N. World Court Team. “If people are afraid to criticize these atrocities for fear of accusations of antisemitism, then future atrocities may be rendered beyond debate and met with silence.”

Another “case study” condemns “The Antisemitism of Boycotting Israel and Charging It with Apartheid.” The authors dismiss the global nonviolent campaign to boycott, divest from, and sanction Israel until it respects international law by ending its occupation, and granting Palestinians full equality including the right to return: “The predominant drive of the BDS campaign and its leadership,” students read, “is not legitimate criticism of Israeli policies or a productive process to support Israeli-Palestinian peace efforts, but the demonization and delegitimization of Israel.”

The case study defends Israel against accusations of apartheid: “The South Africa regime imposed strict segregation laws that banned blacks from white areas, prevented interracial marriages, and regulated the education of black children. . . . No such segregation laws exist in Israel.” Backers of BDS point to the 44-mile winding “apartheid wall” that separates “tens of thousands of Palestinians from their families, property, jobs, schools, medical facilities, and holy places in Jerusalem,” according to the Institute for Middle East Understanding. Furthermore, the “Citizenship and Entry into Israel Law” bars Israeli citizens and Palestinians from the occupied territories from living together as a married couple in Israel. Israel prohibits secular marriages, which effectively bars couples from different religions from being married inside Israel.

Israel denies the right of expelled Palestinians and their descendants to return while its “Law of Return” grants Jews worldwide the right to immigrate for automatic Israeli citizenship. The authors write: “The global BDS movement’s demand for the return of all Palestinian refugees to their former home in Israel effectively calls for the end of the Jewish state of Israel.” The return of Palestinian refugees might presage the end of Israel as a Jewish supremacist state, but the BDS movement’s vision of a state that provides equality for all its citizens, regardless of religion or ethnicity, merits discussion in the classroom.

Reimagining Holocaust Education

While students throughout the United States read Anne Frank’s Diary of a Young Girl to imagine themselves cooped up in an attic for two years, hiding from Nazi storm troopers, few learn of the Nakba. Even fewer are taught the Holocaust and the Nakba simultaneously or back-to-back, not as isolated historical chapters but as interlinked tragedies of scapegoating and ethnic cleansing that continue to this day.

A reading of Anne Frank could be followed by the story of Hind Rajab, a 5-year-old Palestinian girl who dreamed of becoming a dentist. On Jan. 29, 2024, the Israeli military opened machine gun fire and killed Hind, her aunt, uncle, and four cousins as they tried to escape Gaza City in their car. Hind, the last to be killed, was on the phone for three hours with an emergency dispatcher, waiting for an ambulance. “I’m so scared, please come. Come take me. Please, will you come?” she cried in the taped phone call published by the Red Crescent Society after Hind’s body, the bodies of her relatives, and of two ambulance workers who came to rescue her were discovered 12 days later, near the pulverized ambulance.

The editors of The Holocaust and the Nakba argue that we must integrate the teaching of dual trauma to foster an empathetic partnership leading to eventual reconciliation between Jews and Palestinians. An integrated curriculum, according to the editors, would challenge binary opposition of us versus them, and disrupt the narrative of Jews as eternal victims.

Although other K–12 resources, such as Facing History & Ourselves’ Teaching Holocaust and Human Behavior, are not explicitly anti-Palestinian like Echoes & Reflections, all ignore the ongoing genocide in Gaza, where Israel has bombed hospitals, refugee camps, schools, and universities, and imposed mass starvation on 2 million people. Imagine how different Holocaust education would look if it valued not only the stories of concentration camp survivors but also refugees from Zionist expulsion, occupation, and ethnic cleansing.

In his chapter in The Holocaust and the Nakba detailing the Kowalskis’ story that began this article, Confino asks us to imagine a “counterfactual” history, a “what if” scenario: “What would have happened if the Jews, whose justification for settling in the land of Israel derived from the Bible, would have exercised a policy in 1948 based on the principle ‘What is hateful to you, do not do to others’?”

Now that’s a question for classroom discussion.