What’s in the Water?

Teaching About Environmental Racism

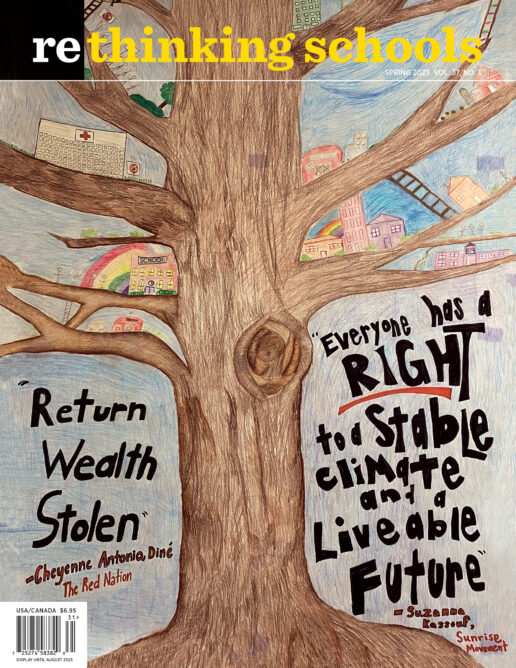

Illustrator: Howard Barry

In the spring of 2016, children in Portland, Oregon, walked into their school buildings to find the drinking fountains shut off, the fixtures dramatically wrapped in plastic and tape, and instructions: Do not drink the water. High levels of lead had been found in the water in almost every single building in Portland Public Schools. At one high school, a classroom faucet delivered water with 57,600 parts per billion of lead to water — the Environmental Protection Agency requires mitigation at 15 parts per billion.

Seven years later, I stood in a hallway on the fourth floor of the newly remodeled Lincoln High School asking a group of juniors and seniors whether the hefty gulp of water I had just sucked down from the water fountain was safe.

I was visiting Lincoln at the invitation of my friend and colleague Tim Swinehart, along with another friend and colleague, Matt Reed. Tim had been approached by student organizers of Black Lives Matter at School, who asked if he — teacher of the school’s Environmental Justice course — would offer a mini-workshop on environmental racism as part of their planned Week of Action events. Tim suggested to Matt and me that this might be a good chance to try out some new curriculum about the struggle to access safe water in places like Flint, Michigan; Jackson, Mississippi; and Newark, New Jersey.

The lesson we workshopped with students grew out of a Democracy Now! special report, “Thirsty for Democracy: The Poisoning of an American City,” which aired in 2016.

The heart of the activity are accounts of residents who suffered (and in some cases continue to suffer) the impacts of the recent water crises in the majority-Black cities of Flint, Jackson, and Newark. Each student takes on the persona of someone whose life is touched by these crises — along with some scholars and experts who offer important background — and hear stories from each other to surface patterns across the different cities. In conversations, they find others who can help answer mixer questions. For example: “Find someone who was directly affected or harmed by one of the water crises. Who are they? How were they affected or harmed?”

Students meet Kawanne Armstrong, a Flint grandmother who tested her water when it started running brown and smelling foul, and found it had dangerous levels of lead. Now she relies entirely on bottled water for herself and her grandson, which is not always easy to come by. Students also meet Kehinde Gaynor of Jackson, who explains the painful calculus of parenting through a water shutdown:

My daughter loves to eat fruit. She says, “Daddy, can I get an apple?” But rather than just grab one and give it to her, I’m weighing washing that apple off with the same bottle of water that we’re using to brush our teeth, to drink, to clean. Do I have enough water to give my daughter an apple?

Students also encounter stories of community activists. Shakima Thomas says that it was her 5-year-old testing positive for lead — a neurotoxin that can permanently damage children’s brains — that pushed her to join the Newark Water Coalition and lobby the city to replace the lead pipes. Nayyirah Shariff works with the Flint Democracy Defense League (FDDL), which organized a door-to-door campaign delivering bottled water, water filters, and replacement filters, and to document people’s stories about the water crisis. Pauline Rogers, whose organization in Jackson offers housing and employment to women coming out of prison, helps students understand how the water crisis compounds other vulnerabilities:

Two of the houses I run are totally without water. Another has severely low pressure. Not having access to water makes an already-hard process of rebuilding your life after prison exponentially more difficult. How are you supposed to get a job if you cannot shower?

Those on the frontlines also share their analysis of the roots of the crises. From Claire McClinton, founder of FDDL, students learn it was Flint’s unelected emergency manager, appointed by the governor, who sought to save money by switching Flint’s drinking water from the Detroit system to the poisonous Flint River, where General Motors had dumped industrial toxins for decades. She insists the Flint crisis is not only a water problem, but also “a democracy problem.” From Kendrick Hart in Jackson, students learn that one of two main water treatment plants in the city is more than 100 years old but that when Jackson is under a boil water notice or water pressure is too low to flush a toilet or take a shower, the water systems in the majority-white suburbs continue to operate without problem. Anthony Diaz in Newark introduces students to the impact of “white flight” on cities like his — today, majority Black and Brown. When white people fled to the suburbs, they took their tax dollars with them, leaving inner cities under-resourced, with crumbling infrastructure and poisonous pipes.

In the mixer, students also meet a handful of experts, people who are neither residents of the cities, nor directly organizing on their behalf, but who share critical context about the systemic causes of the crises. From journalist Judd Legum, students learn that a massive multibillion-dollar corporation — Siemens — brokered a $90 million contract with the city of Jackson to fix the water system, which it utterly failed to do. From hydroclimatologist Dr. Upmanu Lall, students learn that all parts of the U.S. municipal water system need massive upgrades and investment. But, he points out, while the United States has a Department of Energy (which continues to prop up the death-dealing fossil fuel industry), it has no Department of Water to coordinate the vast and critically important undertaking of ensuring clean water for the nation. From Professor Paul Mohai, students learn that although Flint is perhaps the most egregious example of environmental injustice in recent memory, it also follows a pattern evident in every corner of the country: Poor people and people of color are disproportionately burdened by environmental contamination — in their neighborhoods, schools, and homes.

And that is the punchline of this lesson — these water crises are not simply accidents that could have happened anywhere; they are manifestations of racism, past and present, that happen in some places — and to some people — far more than others. As Robert Bullard, known as the “father of environmental justice” and a scholar featured in the activity, says: “Zip code is still the most potent predictor of an individual’s health and well-being.” The injustice faced by the residents in Flint, Newark, and Jackson will not be addressed by just swapping out pipes or building a new water treatment plant, because it is not only a water crisis — it is also a housing crisis, a health care crisis, a governance crisis, a funding crisis, and yes, a white supremacy and capitalism crisis. Kenyatta Dobson, a Flint resident, says she still doesn’t “feel whole” five years after the crisis. Nayyirah Shariff similarly says, “We need Flint residents to be made whole.” What would it require to build a society that allows us — all of us — to feel whole? That is a question we should ask each other and our students.

Back in the hallway at Lincoln High School, I repeated my question: “So, was the water I just drank out of that fountain safe?” Most students nodded “yes.” And they were probably right. In 2017, Portland voters approved a $790 million bond that included $28 million for upgrades to water systems, a project close to completion.

Before we went back to the classroom to do the mixer, I asked one more question: “Would you be as confident about the water at another school in the district — say one of the older buildings, like Jefferson (the historically Black high school in Portland)?” Lots of shaking heads.

“No, I wouldn’t drink the water there. I mean, have they switched out the fountains at all the schools yet?”

Not whole yet.

Resource

The materials for the “Water and Environmental Racism” role play can be found here: bit.ly/water_lesson