“We Cannot Create What We Cannot Imagine”

Helping Students Picture Climate Justice

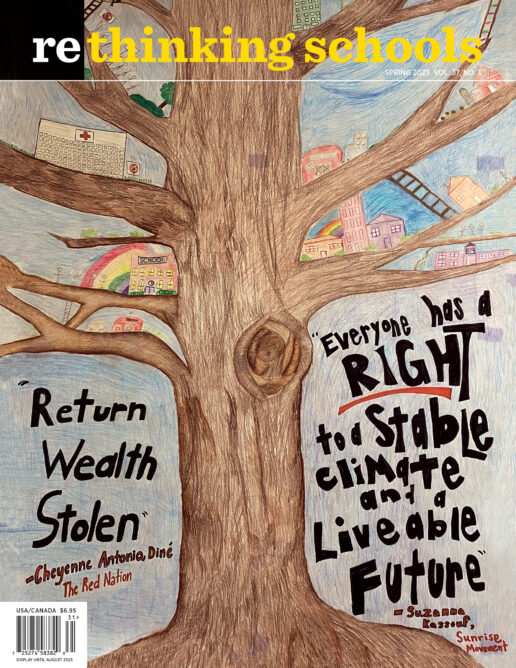

Illustrator: Adolfo Valle

When I woke up this morning, my bedroom was flooded with ominous dark orange light.

I drew the curtains to an apocalyptic scene: a red sun and sepia-tinted street view. Strong winds had fanned fires around Oregon throughout the evening, filling Portland with wildfire smoke.

My thoughts raced back to September 2020. I was beginning my first year teaching. We’d already been quarantined for months by COVID-19 when wildfire smoke ravaged the city, spiraling many of us into existential dread.

This is the world that my students are growing up in. Climate change is not some theoretical, future problem — they see it right outside the window. They’re breathing the smoke, enduring the sweltering heat waves, and grappling with the fallout of COVID-19, itself likely fueled by environmental degradation and natural habitat destruction. Each year, students walk into my class resigned to having “no future.” But last year, my students ended their year in my inquiry class imagining, conjuring, and rendering a future — not of apocalyptic wildfire smoke and mass death — but of solidarity, care, and possibility.

Building Something Different

I teach 9th-Grade inquiry at Grant High School, a largely affluent, majority-white public school in Portland, Oregon. The class strives to help students develop critical thinking skills and social awareness. Throughout the year we grapple with how our society and lives are shaped by identity, power, and history, exploring issues of race, gender, colonization, and more. Kids learn pretty heavy information, from the War on Drugs to gender bias in media to U.S. imperialism. I want students to leave our year together feeling like they don’t have to accept the world the way it is, that they can play a part in building something different.

The lesson described here closed out our year together, as well as a unit on the climate crisis. My students had been working on projects in their physics class, researching and presenting a different consequence of climate change — from wildfires to sea level rise to climate refugees. In our class, we had just finished a “trial” of Exxon, with students prosecuting the company (me) for covering up its own climate research and spreading doubt about climate science. All of this serendipitously coincided with an international student climate strike, where I joined students in walking off campus to protest government inaction on climate change. To prepare, I had shown students the Intercept’s video A Message from the Future with Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. Although this video helps students imagine a better future, I wanted them to forge an understanding of how this future could come about, rooted in the indefatigable work of existing social movements.

This lesson was developed collaboratively with my curriculum collective, Bill Bigelow, Matt Reed, Tim Swinehart, and Ursula Wolfe-Rocca. For the past four years, I have met regularly with this group of educators to develop climate justice curriculum. I joined while still in graduate school and have benefited from the mentorship, camaraderie, and deep knowledge base of my comrades.

Meeting Activists

Wanting my students to realize that they are a part of history, I started the lesson by saying:

Imagine that historians are writing about the 2020s. We’ve had two years in this decade, but there are still eight more. What will they write? With your table partner, fill in the blanks:

“The 2020s was the decade of

_______________”

OR

“The 2020s was the decade when _______________”

The classroom filled with chatter and squeaks of dry-erase markers on mini-whiteboards. After a couple of minutes, I asked students to share their answers.

“The 2020s was the decade of COVID, fires, and riots in the streets,” Mark declared.

“Ah, yes,” I replied. “Who said something similar?” About a dozen hands shot up. “OK, what else we got?”

Connor chimed in, “The 2020s were the decade when Elon Musk colonized Mars.”

“Take me, Elon!” Braden yelled and the room lit up with laughter.

When the giggles faded, Emilia shared, “The 2020s were the decade when we realized we needed to change to survive.”

“Wow! I love that.”

As I passed out the lesson introduction, I said, “We’re going to spend the next few days imagining what the future could look like. Each of you is going to take part in that imagining. You will attend a visioning conference representing organizations working on housing, immigration, Indigenous rights, food and farming, youth activism, jobs, and racial justice.”

We then read the introduction together, which invites students to imagine future generations declaring the 2020s as the decade “when powerful enemies of the Earth — fossil fuel giants and corporate polluters — finally were confronted by an explosion of activism and organizing from students, workers, and ordinary people.” Because it’s important to ground students in real possibility, it continues, “No doubt, the cascading emergencies will be part of it: the horrific heat waves, the worsening and deadly wildfires, Arctic ice melting at unprecedented rates, millions of climate refugees, devastating floods, storms, and droughts. But let it also be remembered for the action, the organizing, the demands of people like you.”

The introduction explains that students’ mission is to work together to create a collective, robust vision of the future they are fighting for.

In a moment, each student would receive a role and learn the story of a real person working on one of these issues.

Students meet Sharon Lavigne:

Growing up, I lived the American Dream. My family lived off bountiful farmland in St. James Parish, Louisiana. We had clean air. Clean water. Soil that could grow anything. Most importantly, we lived free. We owned our own land, a 40-acre farm passed down to my parents from my grandparents. Nearby was Freetown, one of the many Black-led settlements founded by formerly enslaved people that dotted the banks of the Mississippi River from New Orleans to Baton Rouge.

I now own the same 40-acre farm I grew up on. My house, my church, my relatives and neighbors, and everything else that I consider home, are here. I cannot imagine living anywhere else. But my home is no longer the dream I remember. It’s become more like living on Death Row.

But unlike Death Row, there was no judge and no jury. No, what’s killing us is the toxic pollution from the oil, gas, and plastics plants that now surround St. James Parish.

Students also meet Norman Rogers, second vice president of the United Steelworkers Local 675 in Los Angeles, an oil refinery worker who knows we must evolve past fossil fuels to survive:

I fear that without a plan, workers will be sacrificed in the name of profits and progress yet again. That’s why I am working in my union to fight for a just transition. A just transition means that workers like me, alongside fenceline and frontline communities, do not bear the burden of the costs of creating a sustainable economy. We are not sacrificed in the name of a better future. A just transition also means holding companies accountable when they make decisions that harm the communities in which they operate.

Students also meet Leah Penniman, founder and owner of Soul Fire Farm; Cheyenne Antonio, Diné activist from the Red Nation; Alma Maquitico, co-director of the National Network for Immigrant and Refugee Rights; and Tiana Caldwell, organizer with Kansas City Tenants.

One of the awkward things about teaching this lesson is that I chose to include myself as one of the featured activists. I was one of the founders of the Portland chapter of the Sunrise Movement — a youth movement fighting for climate justice. So when my curriculum collective decided we needed a role about youth activism, they encouraged me to share my own story.

Before I distributed the roles, I told students “Some of you are going to read my story as an activist. I feel a little embarrassed about this, but I’m also excited to share this side of myself with you.”

Once students received their roles, I invited them to read and mark them up, with an emphasis on writing notes in the margins — we would use these notes for our next activity. As students read, they looked to answer the following questions from the perspective of their role:

- What struggles are you involved in? What injustice(s) are you trying to address?

- What does the world you are struggling for look like? If you achieved your goals, what would be transformed and how?

As a teacher of 9th graders, I’ve learned that there are words we often use in conversation without fully grasping their meaning; I think it’s important to define them in the classroom. So I shared a definition of “struggle” with them as “a collective effort to achieve something.” Both questions invite students to identify with the courage and determination in these stories, to look beyond the suffering toward a brighter and achievable future.

Found Poems

The great African American poet Lucille Clifton said, “We cannot create what we cannot imagine.” As we wrote in the lesson introduction, “Too often, the future we’re fighting for exists only as an abstraction — ‘equality,’ ‘freedom,’ ‘safety.’ But what do those things actually look and feel like in a society, in our day-to-day lives?” Given that our goal for students at the end of this mini-unit was to create a mural in mixed-role groups, we wanted to ignite their creativity and imagination while processing what they had just read.

I told students, “Now that you’ve spent some time reading, your next task is to create a found poem with other students who read the same role as you.”

To demonstrate, I showed them an example of a found poem created by a member of my curriculum collective using a short article that my class had read in a previous unit as the source text. Displaying the poem beside the article, students could see how powerful words and phrases — highlighted in the original — could be rearranged to both capture the information of the article and creatively express something essential about its message.

To create these poems, students would use not only powerful lines from the roles themselves, but also their margin notes and reflection question answers. Incorporating their own voices allows students flexibility to capture the message of the role in their poem while fanning their creativity.

Students got to work, pulling out their roles and reflections, sharing their writing and lines they found especially powerful. The room was alive with discussion and imagination.

Creating the found poem for Diné activist Cheyenne Antonio, I heard Lucy say, “I think we should include something about the cancer rates — they’re 15 times higher for Native people here than the national average.”

“I thought it was 200 times higher?” replied Tom.

Charlie chimed in, reading from the text, “‘. . . in other parts of the reservation filled with old pit mines, it was 200 times the U.S. average for women ages 20 to 40.’”

Lucy: “Damn, that’s so messed up.”

Across the room, Logan exclaimed, “Yeah! I think we should repeat that line again!”

“Hey, Ms. Kassouf! Can we make a rap?” asked Elijah.

“Sure! That’s a poem.”

The next day as students entered the classroom, I instructed them to sit with their groups and to nominate a reader who would share their poem with the class in a read-around.

I told students, “Though you will attend a visioning conference next, not every group will have every role represented. So listen carefully as people share their poems during the read-around. This is your opportunity to ‘meet’ each of these inspiring activists and learn more about their stories.”

During our found poem read-around, I projected each poem on the screen and told students to write down “three golden lines” that stand out to them for every group.

The poems were beautiful and profound. Here’s an excerpt from the perspective of Tiana Caldwell, organizer with Kansas City Tenants:

No one should have to choose between medical care and a roof

over their head

Having a home or possibly being dead

Home is where the heart is

I shouldn’t have to go through this and neither should my 13-year-old

son

In the current housing system, only the rich have won

KC Tenants is what gives me hope

With this broken system, it helps us cope

Home is where the heart is

Here is the found poem for Leah Penniman from Soul Fire Farm:

Planting a seed

In the ground

To regenerate

Song, dance, and celebration.

Culture and crops

Stolen from home,

Food and tradition surround them.

Healing and harvesting

The next generation,

To end exploitation.

Growing and gathering,

Sharing joy and success.

All around this rich Black tradition.

But unless.

We say thanks to the soil

For its nutrition,

Life has no meaning.

And another (that made me cry) from my role, representing Sunrise Movement:

We don’t need to be perfect.

People like me desperately begging

Begging for their children’s lives

Begging for their future

The world’s people, children,

scientists are screaming

We don’t need to be perfect.

Hostile countries

Enemies of the earth

Selling our future for profit

Everyone has a right to a stable

climate and a livable future

We don’t need to be perfect

Young people fighting

Young people joyful

Young people hopeful

. . .

We don’t need to be perfect. We

just need to show up.

After each read-out, students shared which lines stood out to them.

“You can’t separate the health of the land from the health of the people.”

“The system is broken for people like me.”

“I don’t believe politicians.”

“We are going to win.”

When the poems were finished, I exclaimed, “Wow! That was a powerful experience. Thank you all for creating such beautiful poems. You’re almost ready to attend the visioning conference where you will meet other people struggling for justice like you.”

The Visioning Conference

Before students moved into mixed-role groups, I wanted them to revisit their role one more time to deepen their understanding and to pull out descriptive imagery that would help them illustrate the future they were fighting for. As they read, I instructed them to highlight or circle at least four words or “images” (descriptive sentences) that represent their character’s ideal world.

I then told students, “From the perspective of your role: Imagine that you have won the world that you want — you have been successful in your struggle against injustice! Describe a day in your life in this new world. Use sensory details: What does it feel, sound, look, smell, and taste like? How is it different from the current world we live in and how is it the same? There are no rules here, you can do this in whatever format you’d like.”

Students began constructing narratives, daily agendas, poems, and drawings.

Here’s an excerpt from Claire’s piece, written from the perspective of Sharon Lavigne:

The building’s been torn down, the final of the 150 factories. And the air is crisp, fresh, and clear, just like it used to be when I was a kid. It doesn’t hang heavy in the air, clogging your lungs so thick you can practically see it, practically pull at it with your bare hands. The tree planting helped with that. New trees up and down St. James Parish, lining the road, circling the scars left by the demolished factory.

And another from Bev’s, illustrating Norman Rogers’ life:

5:00 Wake up to the sound of birds chirping outside your window, drink coffee, and sit outside marveling at how quiet the world is in the morning.

6:00 Report to the union offices to lead today’s daily meeting where you learn that your initiatives have helped over 500 workers and counting.

7:00 Meet with fossil fuel worker Dan Jacobs, and help him find a job as a solar farm mechanic.

Here’s Ani writing from the perspective of Alma Maquitico:

The border is quiet, no helicopters, no drones. I stop outside and see no fence between the two countries, only a family of four visiting for summer break. When migrants cross the border, they do it at a checkpoint, not over a fence. They don’t need to. When they cross, nobody is separated, and an official gives them jobs if they need them. Now, fewer people are crossing. Crops at home are worth money and big corporations are not allowed to flood food into Mexico. People own their land and cannot be kicked off.

Steeped in this imagery of the future they want, students were ready to attend the visioning conference. As mentioned, there are seven different activists represented in this lesson. I wanted activists from different organizations in each group in the visioning conference. But to keep mixed-role groups a manageable size — fewer than seven students per group — I created groups of four or five students. On the projector, I displayed which mixed-role group they would be in and reminded students that not every group would have every activist represented. Once they moved into these new groups, they wrote their names on multicolored name tags as I explained, “You will begin by sharing your name, organization, which struggle(s) you are involved in and which injustice(s) you are trying to address. As you listen to one another, note the places where your struggles overlap and where they are different. Once you’ve shared the basics, begin imagining the future you want, one that everyone in the group can agree on. Share highlights from your ‘day in the life’ writing and those words or images that you circled that describe your ideal world.”

After 15 to 20 minutes of conversation, I called out, “OK, everyone! Now it’s time for the fun part. The main goal of our visioning conference is to design murals that can be painted on the walls and hallways of schools across the country that can bring to life the stories of community activists like you. Remember: ‘We cannot create what we cannot imagine,’ so our task is to show people what a better world can look like, to inspire hope and give us a north star to follow.”

Creating is the magical antidote to the suffering of our world.

I wanted these murals to allow students the visceral experience of imagining and building a different future. Students are bombarded daily with news of destruction: the destruction of the planet, the destruction of our democracy, the destruction of Black lives and bodies. To build something different, students need to experience the joy of creation. Creating is the magical antidote to the suffering of our world. By investigating the root of this suffering, we can dig it up and plant something new. Schools are the gardens of our societies, where we can nurture the radical imagination needed to picture a new world, and grow the skills required to build it.

Students got to work, huddling in groups around large pieces of chart paper, scribbling drafts in their notebooks and scheming the best way to depict their ideal future. The room was alive with creativity and conversation.

“We should draw a big public housing complex with plants growing on it!” exclaimed Tara.

“Yeah! And around it, let’s put farmland, so people can grow their own food. We can even have little window gardens on the buildings,” Mari added.

“Let’s have some wind turbines out in the farms.” Sam chimed in. “People from my old fossil fuel union could be putting them up.”

“Ms. Kassouf! Can we get some paint from the art building? We need more color and we’re using up all the markers.”

One of the guidelines for the mural was that all students had to be working on it at the same time — no one could be sitting out.

Students drew and painted farmworkers on green and brown rolling hills, fluffy clouds and clean air, decommissioned fossil fuel infrastructure engulfed by spindly vines and surrounded by solar panels and a smiling sun. Many murals depicted people working together across race and gender, to farm, to build, to celebrate, and to fight. One group painted me, surrounded by other activists, with their healthy and hopeful future emerging from the end of my megaphone.

The murals also included powerful words and phrases: “Treat the Earth as a relative, not a tool.” “Unity, Power, Change.” “Home is where the heart is.”

In my role for the Sunrise Movement, I had written about my favorite song we sang at meetings and protests, adapted from Leonard Cohen’s “Anthem,” and I was delighted to see it depicted on several murals: “Ring the bells that still can ring. Forget your perfect offering. There is a crack in everything, that’s how the light gets in.”

A Better World

Without a doubt, this was the most powerful and joyful lesson that I taught all year. In my role, I had written about the overwhelming fear and grief that I experienced as I realized the magnitude of the climate crisis as a young person. For me, the only antidote to this pain was action. In the Sunrise Movement, I found my voice, my power, my community, and my agency in shaping the world around me.

This is what we strove to give students in this lesson. The future is not fixed, it is malleable, and students can play a role in building the future they want to live in.

On our last day of school, after a year of uncovering the pain of our world, our classroom was covered with images of what a different world could look like: one of solidarity, connection with the natural world, harmony between peoples and nations, and strong, thriving communities.

In her final reflection, Marie wrote “This project reminded me that a better world is possible. I think that is extremely valuable especially right now when everything feels hopeless. I learned that it’s important to keep fighting for a better world.” l

Resources

The materials for the “Imagining the Future” role play can be found here: bit.ly/3UmYqcj

The sample found poem can be found here: bit.ly/3UdKqkY