Voices of Black Liberation

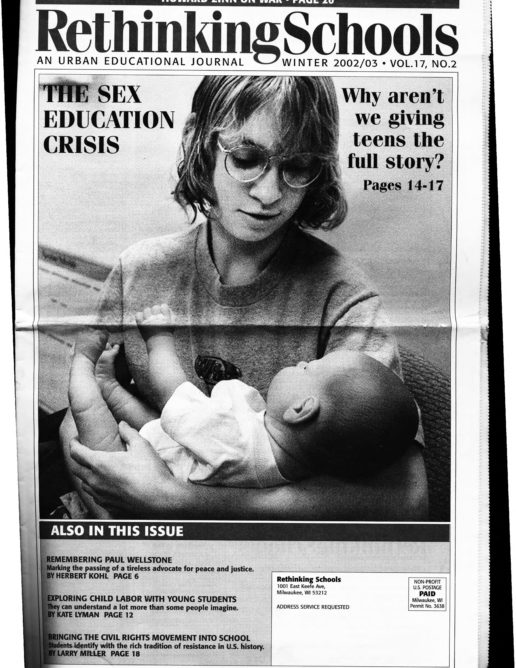

Illustrator: Brown Brothers Photography

-photo: Brown Brothers Photography

This roleplay concludes my five-week Black liberation unit. It’s one way for students to become familiar with the writing and speeches of famous leaders of the Black Liberation movement.

First, my students review speeches and popular writings of leaders of the Black Liberation Movement in the 1950s, 1960s, and earlier. I chose the following leaders to represent a broad spectrum of opinion: Booker T. Washington, “Speech Before the Atlanta Cotton States”; W.E.B. DuBois, “Men of Niagara”; Marcus Garvey, “Masters of Your Own Destiny”; Paul Robeson; Fannie Lou Hamer; Malcolm X, “Ballot or the Bullet”; Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., “I Have a Dream”; Barbara Jordan, “Who Will Then Speak for the Common Good”; Stokely Carmichael, “Black Power”; and Huey P. Newton. (Links to the speeches and writings I give my students are available here.)

Students can work alone or in pairs, representing one of the leaders. In larger classes more than one group represents the same person. They read documents I provide and write a speech, in their own words, representing the views of their assigned leader.

Once finished, the students give their written speeches. While the students speak, I outline their arguments on the chalkboard. Once all the students are finished giving speeches, we compare each person’s perspective, ensuring that the views represented are accurate and emphasizing the similarities and distinctions. I then ask the students to put the board notes into their notebooks.

Afterwards, we hold a debate. The students are required to argue the views of the people they represent, even if they have disagreements with those views. I spend time with the students as they prepare for the debate, asking them to give me the arguments they plan to present. I do this to make sure that their arguments accurately represent the views they are presenting. And I also ask students to write a list of statements that would make clear their disagreements with other leaders’ perspectives. While doing this, I ask them to write down any criticisms they have of another person’s point of view.

THIS YEAR’S DEBATE

This year I started the debate by asking all students to respond to the question, “What is your plan for achieving full freedom for the Black community?” One student stated, “I want to repeat what I said in my speech. I, Booker T. Washington, want all of you to learn how to build homes, farms, and to read. I know that when we are educated, we all will fit with the white people. Education is the key.” There was a quick response from nearly all students criticizing Booker T. Washington’s view of seeing education as the only strategy. A student representing Malcolm X said, “We aren’t here to fit in with the white man. We must end white racism and free our communities. The white man doesn’t want the Black man to do anything good. They just want you to do bad so they can put their club upside your head.”

In another class, students emphasized differences between DuBois and Washington. They realized from their reading that much of what DuBois said was criticizing Booker T. Washington for believing only in education and not fighting against Jim Crow segregation and the rampant violence that faced African Americans at the time.

Students representing Fannie Lou Hamer and Barbara Jordan made it clear that “we cannot just work outside the system but must also fight prejudice and racism within the system. And that includes the Democrat and Republican parties.”

In one class, a student representing Marcus Garvey confronted others by challenging them to follow him because “You must always seek and work for a government absolutely your own and I’m the person to lead you to this.” Someone representing Huey Newton asked, “The only way to freedom is to follow you and your businesses? What about uniting with people in other races that support us? What about poor people who aren’t Black?” The Garvey group responded, “They aren’t going to help us, especially the rednecks. We have to depend on ourselves. No people have ever been free without their own nation. It’s the only protection our race can have.”

Stokely Carmichael’s approach to Black power was portrayed by students as “Black people getting it for themselves, that is, power to choose their own leaders, build and live in their own communities, and not be forced to integrate with whites to be free.” The students representing Reverend King’s perspective said, “We are all of the human race and integration of races is the final goal in our freedom struggle.”

Those representing DuBois replied, “We need both. We need Black power but we also need to be alongside other nationalities in making the world free.”

DISCUSSING FREEDOM

The reading from Malcolm X was from his early years where he called whites the “devil.” Here students said, “There is no way we can work with those devils.” Another student then asked, “Didn’t Malcolm X change his view about whites?” I told the class that Malcolm X did change his thinking in the sense that whites could be united with if they were serious about fighting racism and oppression. He was not calling for integration but calling for all people to fight against the racist white power structure. If at any time the debate slowed too much, I would take on the role of one of the leaders and put forth a statement criticizing others, making my statements as provocative as possible to bring out comments.

Students were then asked to discuss the struggle for freedom from their own perspectives, pointing out when they agreed with the historical figures we studied. It quickly became clear that most students did not fully embrace or reject any one person’s view but instead held an eclectic perspective that combined Garvey’s call for economic development, Malcolm’s call for Black identity, Reverend King’s demand for full equality, Booker T. Washington’s stress on the need for education, Huey Newton’s emphasis on the “people” and base-building in communities, Fannie Lou Hamer’s call to work inside the political parties, and Barbara Jordan’s demand to hold public officials accountable.

I also asked students their opinion of Paul Robeson’s, Stokely Carmichael’s, and W.E.B. DuBois’ call for unity with the struggles of Africans and other people around the world fighting for freedom. Students tended to agree with one student who said, “We are really all one race in this world, the human race, so we must help each other.” There was also a strong sentiment as stated by another student that, “We can’t really help others until we can help ourselves.”

The final work of this unit was for students to write a summary of what they learned from studying the Black Liberation strategies and explain any impact this knowledge could have on their lives. Desiré wrote, “It has helped me think differently than I did before. I appreciate more what people have done for me in the past . If you stand for good, things will get better.” Clem said, “I look forward to people questioning me about Black history. I know my people stood up and they were very smart in deciding strategies, even when they disagreed.”

RESOURCES

Videos

“Eyes on the Prize: America’s

Civil Rights Years 1954-1965″

(available in most urban public libraries)

“Eyes on the Prize II: America at the Radical Crossroads 1965-1985”

PBS Video

1320 Braddock Pl.

Alexandria, VA 22314-1698

Ph # 703-739-5380

Murder in Mississippi. 1990.

Directed by Roger Young.

Books

Bullard, Sara.1989. Free At Last: A History of the Civil Rights Movement and Those Who Died in the Struggle (Montgomery, Ala: Teaching Tolerance).

Civil Rights Education Project

400 Washington Ave.

Montgomery, AL 36177-9621

Ph# 205-264-0286

Williams, J. (1987) Eyes on the Prize: America’s Civil Rights Years 1954-1965. (New York, NY: Penguin)

Rethinking Schools website

The State of Louisiana “Literacy Test” (Used to prevent African Americans from voting until outlawed by the 1965 Voting Rights Act.)

Links to the full text of all the speeches mentioned in this article.