Transforming Teaching

Milwaukee’s teacher-run councils helped enrich districtwide reform. Their demise leaves a vacuum for progressive teachers searching to promote classroom-based innovation.

Nearly a decade ago, African educator Asa Hilliard spoke to a gathering of elementary school teachers and principals in Milwaukee, stressing the central role of teacher knowledge and attitudes in any reform effort. “Curriculum is what’s inside teachers’ heads,” he reminded us.

The significance of Hilliard’s remarks went beyond the group, which consisted of the entire staffs from seven Milwaukee schools. “That inservice was the start of something big,” recollects Steve Baruch, coordinator for the Milwaukee Public Schools (MPS) Leadership Academy and an organizer of the January 1989 event. “Most people don’t know it, but it was from there that many of the teacher councils, particularly the Multicultural Council, got their start.”

For most of the 1990s, a network of teacher-led, districtwide councils had a significant impact on reform in MPS. In particular, the councils provided a way for progressive teachers to promote student-centered, anti-racist curricular reform.

The councils are now largely gone. They fell victim to, among other things, budget cuts, changing priorities within MPS, and a national reform effort driven by standardized test scores and “get tough” policies. But the lessons learned from the councils can shape discussion on how to promote grass-roots, district- wide reform that focuses on changing classroom practice and promotes a curriculum appropriate for our increasingly diverse and multicultural society.

Kathy Swope, former co-chair of the Multicultural Council and currently over-seeing the district’s performance assessment, argues that the councils’ strength was that they “gave an official forum for classroom teachers to comment on various issues and to influence district policy. The councils viewed teachers as the experts. We had teachers teaching teachers, giving workshops, organizing conferences and inservices, and developing materials. The feedback was almost al- ways that our workshops were more useful than many which were not led by teachers.”

The original councils included the Multicultural Curriculum Council, Whole Language Council, Early Childhood Council, Ungraded/Multi-age Council, and the Humanities Council. Eventually a Bilingual Council, Library Council, Reading Council, and Health Council formed. In 1994, a Council of Councils was organized to coordinate the councils and to improve their ability to learn from one another.

The councils’ approach contrasted sharply with the top-down approaches that characterize many school reform initiatives. The Milwaukee councils were effective because they were:

- Integrated into a districtwide curriculum reform effort with explicitly anti-racist goals;

- Led by classroom teachers;

- Organized throughout the district and across school lines;

- Focused on classroom teachers sharing their best practices.

In addition, the councils went beyond one-time inservices, and institutionalized teacher collaboration, mobilization, and training. They also recommended and provided money for classroom resources.

COUNCIL ORIGINS

Each of the councils had separate beginnings but all were tied to teacher-led initiatives and progressive curricular philosophies.

“The Multicultural Curriculum Council grew out of the Asa Hilliard inservice,” Baruch recalls. “Representatives from the seven schools got together first as a study group of the Portland, OR, African-American Baseline Essays, and then the whole thing blossomed. About a dozen schools that had demonstrated a commitment to multicultural education were invited to send representatives and the Multicultural Council was formed.”

Eventually, the Multicultural Curriculum Council included members from almost every school in the district.

The Whole Language Council had its origins in the district’s process in 1987 for adopting an elementary reading text-book. Three members of the textbook committee issued a minority report critical of traditional basal reader teaching methods. That ultimately led to an “opt- out” provision, whereby individual schools were permitted to submit a whole language reading instructional plan to replace the traditional basal reader collections of short stories and work sheets. Instead of receiving the new basal readers, the “opt-out” schools received money to buy children’s literature, big books,

and other materials. Thirteen schools opted for this provision. Teachers from those schools met, held joint inservices, and formed the Whole Language Council in fall 1988.

The councils received financial support from the general MPS budget up through 1996, when funding was cut off. They received on average about $25,000 a year, although a few received about $100,000 during their initial years. The larger budgets were either for district-wide inservices, such as those of the Early Childhood Council, or for programs to provide grants to schools. These grants, ranging from $1,000 to $10,000, were to buy materials, pay for specific staff workshops, or hire community people for school-based projects

DISTRICT WIDE REFORM

The councils developed in the context of an even broader curricular reform effort within MPS — the K-12 Teaching and Learning Initiative. This reform, in turn, emerged at a time when the national education climate was more focused on curriculum innovation and on embracing our country’s multicultural heritage and future.

The Milwaukee K-12 Reform, as it came to be called, was started in 1989 under then-Superintendent Robert Peterkin. It involved thousands of teachers and hundreds of parents and community people who worked over many months to develop the initiative’s 10 teaching and learning goals (see box, page 12). K-12 played a significant role in shaping nearly all reform initiatives at the time; though rarely mentioned anymore, it remains official district policy.

The reform’s spirit is best captured in its self-description: “The K-12 Teaching and Learning Initiative is a mobilization to improve teaching and learning in the Milwaukee Public Schools … It aims to offer all children an equitable, multicultural education; and teach all children to think deeply, critically and creatively.”

Four teacher councils — the Multicultural Curriculum, Whole Language, Early Childhood, and Humanities Councils — played especially important roles in the K-12 reform and helped ensure its emphasis on equity and multicultural education.

“The councils are what gave flesh to the [K-12] policy,” explained Swope. “In order for policies to actually effect class- room practice, you need teachers to develop strategies, try out resources, collaborate, and share their successes. This was done and led by teachers. That’s why the councils were so powerful.”

Cynthia Ellwood, the central office administrator who led the K-12 reform effort, explained, “The councils were about mobilization and identifying people who were particularly competent and insightful teachers. They simultaneously modeled good teaching pedagogy and gave very specific teaching ideas, along with the necessary books and materials. In fact, the councils help set the [reform] agenda for the district.”

TEACHER LED

Both K-12 and the teacher councils were based on the belief that improving classroom practice is the key to district-wide reform. The structures of most schools, however, reinforce teacher isolation. Teachers have little time to collaborate with their colleagues across the hall — to say nothing of getting together with teachers from across the city. Few school reform projects have successfully wrestled with this dilemma. Instead, they rely on experts who no longer teach in the classroom, or on “teacher-proof” curriculum with pre-determined lesson plans that leave little room for addressing the specific needs of one’s students.

The Milwaukee teacher councils took a different approach. Teachers were seen as leaders and chaired all the councils. To make this possible, central administrative funds were allocated to pay for substitutes so classroom teachers could be released during the day to work on council business. The decision to pay for substitutes was key to the councils’ success. Without paid substitutes at the elementary level reading resource teachers and program implementors — who don’t have classrooms and thus can leave the build- ing more easily — tend to take the lead on districtwide committees.

At the high school level, it is usually department chairs who influence district policy. The Humanities Council, however, “gave more people a chance to have input into district policy,” notes Andrea Loss, a former member of the council and currently an English teacher at Metro High School. The Humanities Council provided “a great opportunity for social studies and English teachers to make curriculum connections.”

Funds were also available to pay teachers for after-school council work. One lesson, however, was that all-day planning sessions were more effective. “It’s hard at the end of the day to be creative,” notes Mary Ellen McCarty, former chair of the Early Childhood Council.

CROSSING SCHOOL LINES

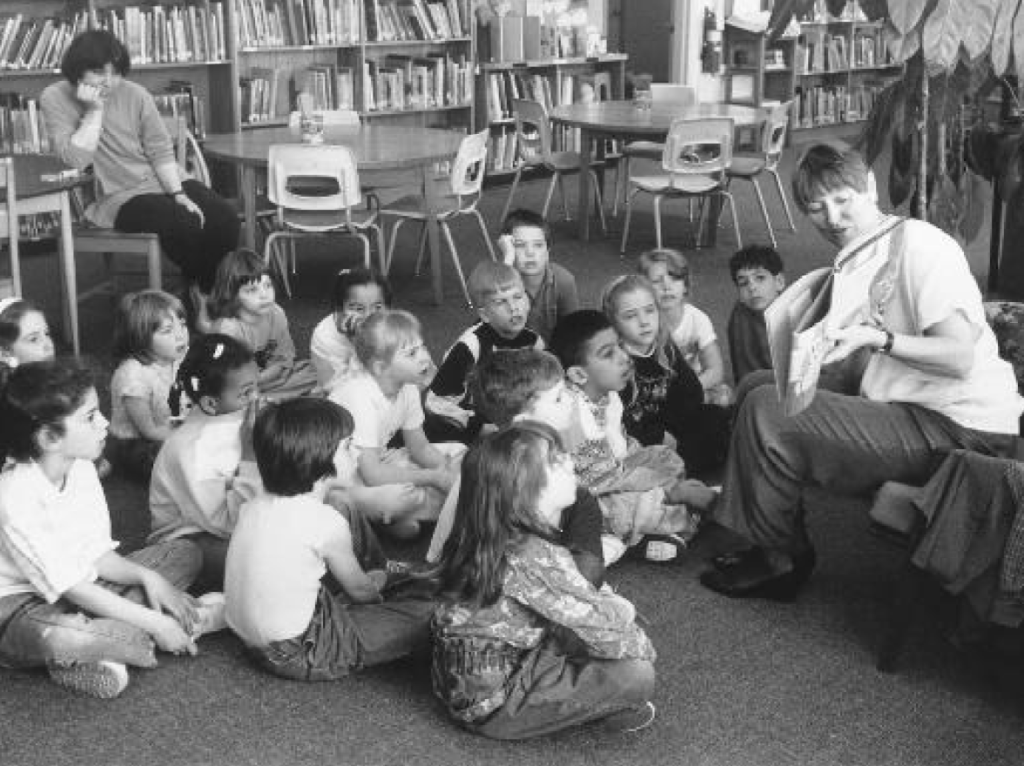

The councils promoted ongoing discussion among teachers at different schools. They brought together some of the most committed teachers and gave them time and resources to help educate and mobilize other teachers. Through workshops, conferences, inservice courses, newsletters, and resource vendor fairs, the councils’ impact was felt throughout the district.

The most extensive example is the work of the Early Childhood Council, which was founded in 1991. The council coordinated a series of workshops to help teachers improve their teaching and implement the K-12 reform. In 1992-93, for example, every single kindergarten teacher in the district was released for three days to attend workshops led by class- room teachers with outstanding practice. The following year, all first grade teachers attended similar inservices, with a new grade level inserviced each year for two more years.

“The workshops touched every early childhood [K-third grade] teacher,” explained Mary Randall, a kindergarten teacher, now retired, who was former chair of the Early Childhood Council. “We had teachers — new ones and experienced ones — learning about the very best techniques from people who were excellent classroom teachers.”

BEST PRACTICES

The councils didn’t rely only on inservices to promote quality teaching. The Whole Language Council funded entire staffs from participating schools to attend workshops of the National Writing Project. The Multicultural Council held quarterly after-school meetings and an annual weekend conference which high-lighted exemplary teacher practice. Most councils put out newsletters highlighting resources and inservice opportunities.

The Humanities and the Multicultural Councils both made menus of quality multicultural literature and teaching guides. The councils provided schools with the funds to buy materials from the menu and then held workshops on how to effectively use the materials in the classroom.

Some of the councils also put out specific teacher guides. The Multicultural Council, for example, published a “Guide for Implementation of Goal 1 of the MPS K-12 Teaching and Learning Initiative.” Despite its lackluster title, the guide provided both a theoretical explanation and specific lesson plans and resources for teachers to deal with the difficult issue of anti-racist education. The Early Childhood Council piloted early childhood screening methods and prepared a video tape to help teachers. It also put out a kindergarten guide to hands-on learning and developmentally appropriate instruction. The Reading Council developed districtwide reading curricula.

While emphasizing lessons from classroom teachers, the councils also brought to Milwaukee a number of well-respect- ed experts, such as James Banks, Howard Zinn, Enid Lee, Gloria Ladson-Billings, Bill Bigelow, Asa Hilliard, Nancy Schniedewind, and Carlos Cortez.

THE DEMISE

Most of the councils ceased functioning during the 1996-1997 school year. A number of factors contributed to their decline, including district budget cuts, the push for decentralization, a refocusing of the curriculum reform effort on school-to-work, and weaknesses within the councils themselves. (Not all the councils have completely dissolved. Former members of the Multicultural Council, for instance, have reconstituted them- selves as the Multicultural Curriculum Education Advisory Board and they continue to hold workshops. Likewise, former members of the Early Childhood Council still meet regularly, put out a newsletter, and host an annual kindergarten conference. While these activities are testimonies to the tenacity and commitment of certain teachers, they in no way fill the void created by the overall demise of the councils.)

State-mandated revenue caps increasingly squeezed the MPS budget through- out the mid-1990s. In response, the school board slashed programs such as summer school and staff development. At the same time, under the leadership of then- Superintendent Howard Fuller, the school board started to radically decentralize many services. One result was increasing pressures to cut funds in the Curriculum and Instruction division at Central Office that had funded the councils. Without money for substitutes and basic operating expenses, most council activities slowed down. Moreover, without adequate funds for districtwide inservices, some councils increasingly found themselves preaching to the converted. These factors sapped the vitality of several councils and hastened their dissolution.

One lesson is painfully clear. Radical decentralization can undermine progressive reforms that are centrally coordinated. With the defunding of the councils and of inservices paid for by central office, a coordinated emphasis on developing and promoting anti-racist curriculum has all but evaporated within MPS.

The councils were also affected by the district’s emphasis on school-to-work reforms during the mid-1990s. While district administrators presented school-to-work as an extension and deepening of the K-12 reform, in practice the initiative refocused many peoples’ energies. Some elementary schools, for example, set up banks and stores instead of organizing multicultural activities. Other indications of the district’s emphasis on school to work: all schools had to identify school-to-work coordinators, and inservice funds were concentrated on school-to-work.

The councils also had their shortcomings. They would have been in a much stronger position to prevent their defunding if they had done a few things differently. For instance:

- The councils could have done a better job reaching out to a wider network of teachers, particularly connecting council representatives to classroom teachers who were not council members. This problem became exacerbated as budgets were cut, and some councils became too ingrown.

- Some councils could have increased their advocacy role. For example, the Multicultural Council “could have taken a stronger stand in favor of the African-American immersion schools,” according to Baruch. At the same time, the Early Childhood Council successfully advocated for an expansion of K-4 kindergarten and improved assessment tools in the SAGE project to reduce class size.

- The councils could have fought harder to institutionalize their status, perhaps through the teacher union contract. One problem is that, until the end, the councils were dependent on the administration’s and school board’s spending whims.

Had the councils been promoted by a visionary superintendent or school board, conditions in the district might be different today. The mobilization of progressive teachers, so necessary for district-wide school reform, might have continued and expanded.

Relative to the overall budget of MPS, the money spent on the teacher councils was minuscule. The results, however, were immense. The councils inspired hundreds, at times thousands, of teachers. As McCarty of the Early Childhood Council said, the councils were “the only spark in teachers’ lives to learn new techniques and reaffirm the positive things they were doing.”

While there is no scientific way to measure the councils’ effectiveness, one could argue from the vantage point of Asa Hilliard — that the councils had started to change “what’s in teachers’ heads.” It is an unfinished task.