Tough Times Under Tommy

Wisconsin Budget Crisis Hits Children & Schools

The first kindergarten in the United States was founded in 1856 in Watertown, Wisconsin, and Milwaukee residents have traditionally benefitted from that legacy. Four-year-old kindergarten has been taken for granted as much as cool summer breezes off Lake Michigan.

But due to a severe budget crunch, Milwaukee Public School officials have proposed the unthinkable: eliminating four-year-old kindergarten.

“Do we want to raise property taxes and keep four-year-old kindergarten? Those are the choices we may have to make,” said Mary Bills, a school board member who heads the Budget Review Committee.

The MPS dilemma follows Gov. Tommy Thompson’s proposed state budget — a proposal that State Superintendent of Schools Herbert Grover has dubbed “the poorest set of educational initiatives I have ever seen from a Wisconsin governor.”

Among other things the budget reduces the proportion of the state’s share of education costs and imposes cost controls on local district spending regardless of enrollment increases. While the proposal makes little educational sense, it’s politically geared to win Thompson support as a governor who proposed a state budget without any general tax increase.

Instead, the tough decisions are passed on to local school boards, which are faced with the unpopular prospect of both raising property taxes and cutting programs just to meet increased costs and higher enrollment.

Estimates are that the Thompson budget will force school boards statewide to raise property taxes an average of 9%, with many districts facing double-digit increases.

Unless property taxes are raised in Milwaukee, MPS faces an estimated $33 million shortfall under the Thompson plan.

Other districts in the state are also facing severe budget problems. In West Milwaukee, for example, officials say they may have no choice but to close one of the district’s three high schools.

Thompson’s Proposals

The Thompson budget has also been criticized by the legislature’s Joint Finance Committee, which has said it will start from scratch on drafting a 1991-93 state budget rather than use Thompson’s proposal.

Sen. Gary George (D-Milwaukee), Joint Finance Committee co-chair, has said he does not want to raise income or sales taxes to increase state revenue, but might consider ending the capital gains tax break for those buying stocks and investments (see story this page). The committee hopes to finish work on its budget by June 10, with the legislature hoping to pass a budget by the beginning of the new fiscal year on July 1.

The state legislature and local school boards are in the midst of budget discussions and figures and proposals are still in flux. But the broad outlines of the debate are set. The proposals in Thompson’s $26 billion budget for 1991-93 include:

- Reducing the proportion of state funding for schools, from about 45% to roughly 43%, according to the Department of Public Instruction. The state level of school funding has decreased under Thompson, despite his campaign promises in 1986 to raise the Wisconsin level to the national average of 50%.

- Limiting local school district spending to the rate of inflation, regardless of whether there is increased enrollment. Only schools would be subject to cost controls, not cities, villages, towns, or counties.

- Reducing reimbursement for handicapped education programs from a rate of 59% this year to 53% in 1991-93; cutting reimbursement for bilingual/bicultural education from about 52% to 41%, according to the state’s Department of Public Instruction. While the actual dollar figures will increase over the two years, demand has increased for both handicapped and bilingual/bicultural programs. The number of limited English-speaking students in the state has risen from 4,684 in 1980 to 13,120 in 1990, according to the Department of Public Instruction.

- Expanding Learnfare to include children ages 6 through 12. Under the controversial program, which currently affects teens 13 to 19 years old, families on welfare have their benefits reduced if their children routinely skip school.

- Mandating school and districtwide comparisons and establishing uniform statewide testing at grades 3, 5, 7, 9, and 10, beginning in fiscal year 1994. Currently, the only statewide testing is a 3rd grade reading test.

- Dividing the Milwaukee district into four smaller systems beginning in 1993-94.

The controversial school “choice” program, under which public dollars are used to send low-income children to private, non-sectarian schools in Milwaukee, would continue next year. As of January, 259 children were participating in the program, the first in the country in which public dollars are used for private schools.

Several alternatives to Thompson’s budget are in the works, although observers say it is too early to predict which may win out.

Sen. Joseph Leean (R-Waupaca) has introduced a bill that, among other things, raises the state sales tax from 5% to 6% and eliminates 41 goods and services that are currently exempt, such as attorney’s fees and consulting fees. Although the sales tax is regressive in that it disproportionately affects poor-and middle-income people, it would raise roughly $918 million more a year in revenue, according to the non-partisan Legislative Fiscal Bureau.

The Wisconsin Education Association Council, which represents about 55,000 teachers around the state, has also put together proposals aimed specifically at MPS. The proposals have not yet been introduced as legislation, although WEAC officials hope they will be part of the budget debate.

The proposals range from early childhood programs at each elementary school; before and after-school daycare; up to $100 million to build neighborhood schools in the central city; increased school-based management; and providing a range of social services at the schools.

Local Cutbacks Seen

For now, however, the immediate problem facing MPS is the budget shortfall. So far the only cut that has been approved by the Milwaukee school board is reducing music and enrichment summer school for elementary and middle schools from six to four weeks. Remedial programs and high school summer school will remain at six weeks.

Bills said the school board is due to receive a budget proposal from MPS officials in late May. She said she hoped the board could approve a final budget at its June meeting. Cuts that MPS officials reportedly are considering include:

- Eliminating four-year-old kindergarten;

- Moving 300 teachers such as librarians, reading specialists, and other support staff into classroom teaching;

- Reducing busing costs by combining routes;

- Eliminating driver education;

- Reducing the interscholastic athletics program by 10%;

- Reducing the number of case managers for exceptional education;

- Reducing evening school to only one semester;

- Reducing money for academic competitions;

- Reducing money for the city music festival;

- Eliminating 64 administrative positions at the central and service delivery area offices.

While the immediate need is to survive the current crisis, a long-term solution must address issues such as funding equity, tax structures, and the special needs of poor and disadvantaged students, according to many education activists.

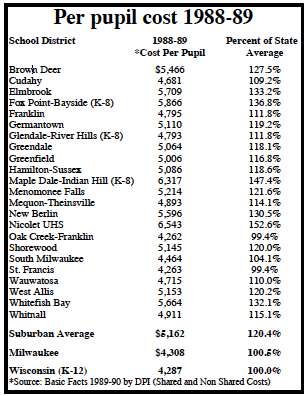

Affluent school districts “can spend more per pupil and tax property less, and the state allows that to continue,” said Doug Haselow, chief lobbyist for MPS. “No matter how you cut it, that’s not equal.”

“In the metropolitan area, we are surrounded by suburban districts that can spend on average about 20% more than MPS and have a tax rate that’s about the same,” Haselow added. “They seem to portray us as a big spender, and we spend less than all of the districts around us” (see chart).

Haselow said the issue also goes beyond the amount of money spent per child, and that there are increased demands on MPS because of the number of poor children in the city. Statewide about 11% of school-age children come from families receiving welfare. In Milwaukee the figure is 44% and in the Milwaukee suburbs it is only 3%, according to MPS data.

One solution is to boost state aid to districts with high numbers of poor children.

“I would like to see financial equity behind every student,” Haselow said. “The real need is to provide additional state aid where there are concentrations of poverty and the kids need more support services.”