Preview of Article:

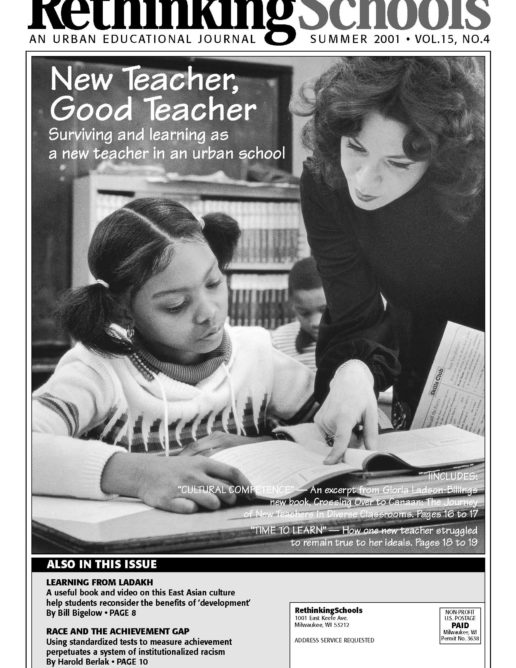

Time to Learn

The first year of teaching can be an exhausting nightmare. Here's how one teacher not only survived but stayed true to her vision of good teaching.

Yet my fears persisted. The kind of teacher I wanted to become was fairly clear in my mind. But it seemed to have nothing to do with the reality I experienced every day.

I knew I wanted to build a classroom community in which students feel safe, both emotionally and physically. I wanted each student to be able to bring his or her cultural background and experiences into the classroom and to feel important and valued. I hoped to create an atmosphere of respect and cooperation. I wanted students to “behave themselves” without feeling threatened or burdened by punishments. I was also committed to high academic expectations, and helping each student learn and progress. I wanted to infuse an anti-racist, social justice perspective into my classroom and hoped to share my own activist background with my students. I wanted to encourage my students to think critically and to learn to take action to create a more just world.

I taught in a two-way bilingual classroom (with both English-dominant and Spanish-dominant students) and I knew it was going to be a challenge to meet my students’ diverse cultural and academic needs, especially in reading and language proficiency. I knew that as an Anglo teacher in a classroom of Latino and African-American students, I would have to examine my actions and interactions through a critical lens. I knew I would have to listen to parents and to other teachers, especially parents and teachers of color.

REALITY

Reality soon set in. I struggled with discipline, organization, and curriculum. I felt disillusioned when my students seemed more comfortable with an authoritarian style rather than one which emphasized self-discipline. I found little support for teaching about social justice and anti-racism. Administrators, colleagues, and classmates in my certification program were willing to listen to my ideas, but did not respond as enthusiastically as I had hoped.</p