The Year in Review

Focus on Charter Schools, Privatization, and Financing

The school year got off to a rough start in two of the three largest school districts in the nation: it didn’t start. Problems with asbestos and facilities delayed the opening of New York City schools for one week, while a $298 million budget shortfall delayed Chicago’s opening for a similar amount of time. New York and Chicago epitomized problems faced by thousands of school districts around the country: deteriorating facilities, inadequate budgets, and declining financial bases.

Such problems set the backdrop for a turbulent year of school debates, some of which had rather ironic twists. A Democratic President signed federal school legislation that was initiated by his Republican predecessor. People on both sides of the private school “choice” debate championed charter schools to further their political interests. Sectors of the business community had ample advice for schools — ranging from “school to work” initiatives to plans to turn schools into for-profit ventures — and yet remained incapable of cleaning up their own back yard and creating a sufficient number of family-sustaining jobs.

The voucher controversy dominated the national education debate in the beginning of the school year. All eyes were on California, where a referendum was held on a plan to give children $2600 each to attend private schools, including religious schools. Voters rejected the proposal by almost a 2-1 margin, handing voucher proponents their third major defeat in four years. (Colorado voters decisively rejected a similar measure in 1992, as did Oregon voters in 1990.)

While voucher supporters blamed their defeat on a well-financed opposition, several commentators noted that the referendum was poorly conceived, its financial impact uncertain, and its potential popularity undercut by schisms within the voucher movement. One problem, for example, was lukewarm support from Republican conservatives in the suburbs, who tend to be happy with their schools and who already have a measure of choice by being able to choose where they live.

Although the voucher movement was stunted, it was by no means stopped. A private school choice plan was proposed for New Jersey (see article p. 7), and pro-voucher forces are expected to launch a number of initiatives in the fall.

While the controversy over vouchers subsided temporarily, the fundamental question facing public education remains unanswered: Will this country provide the resources and commitment necessary to ensure that all children receive a quality public education, or will it allow market forces to prevail and, in essence, dismantle the very concept of a public education system? Various answers to this question were reflected in the debates around charter schools, privatization, and school financing.

Charter Schools

One of the more complex phenomena during the year was the charter school movement. By school year’s end, there were 12 states that had passed charter school legislation and the movement was clearly gaining momentum.

No clear definition exists of charter schools. Like many terms it is defined in the arena of political struggle. Legislation varies state by state in terms of the number of charter schools permitted, their ability to circumvent collective bargaining, their openness to serving all students, and their accountability to the public.

Some forces view the movement as a skirmish in the battle for private school vouchers. The American Alliance for Better Schools — an affiliate of the Americans for School Choice, whose board includes voucher proponents such as former secretaries of education Lamar Alexander and William Bennett — explicitly calls on the voucher movement to embrace charter schools as a way to further a privatization agenda. Further, charter schools have been viewed as a mechanism for allowing for-profit firms to run public schools. The first contracts for the for-profit Edison Project, for instance, are with Massachusetts to run three charter schools.

On the other side, many parents, community activists, and teachers view charter schools as a way to help reform a public school system too often beset by bureaucracy and inertia. Such supporters argue that charter schools, if developed with sufficient attention to equity and public accountability, could serve as models of innovation. (See article on p. 3.)

For-profit Schools

Often related to, but separate from, the charter school movement, was the unabated push to allow for-profit ventures to run public school. Two firms dominate the field: Education Alternatives Inc., (EAI), based in Minneapolis, and The Edison Project, the brainchild of Chris Whittle, of Whittle Communications in Knoxville, Tenn.

It was a rough year for EAI, although a good year for certain EAI executives. EAI found itself unable to break into any new school districts, and by mid-May its contracts were still limited to Baltimore. EAI began running nine Baltimore schools in 1992-93; controversy was such that even though the firm this year won contracts to run three additional Baltimore schools, its role was explicitly limited to non-academic affairs in the new schools. Perhaps the biggest blow was in Washington, D.C. Negotiations for a hoped-for contract in the nation’s capital — a contract that would have been a marketer’s dream — were halted when opposition surfaced in the African-American community and it became clear that proceeding would split the school board. Likewise, the company had put high hopes on Milwaukee. When EAI was dropped from discussions there, its stock dropped $5 in one day.

The company was beset by other problems. Its stock plunged from a high of $48 per share in the fall to a low of $9.75, bouncing up to the mid-teens by May.

Further, the company was told it must pay back $338,500 to Baltimore, money it received based on inflated enrollments. The company was also the target of two lawsuits: one by the teachers’ union in Baltimore, and the other by two shareholders charging that investors were misled about the company’s finances in order to inflate the stock price.

News wasn’t too bad for top EAI executives, however. Founder and CEO John Golle made $1.9 million in salary, bonuses, and sales of stock options, while President David Bennett made over $600,000 in the same manner.

Because the other main for-profit venture, The Edison Project, is a privately held company, the financial information necessary to gauge its long-term viability is unavailable. Despite the marketing hoopla that surrounds the company, prospects are not overwhelmingly good. The Wall Street Journal noted that Whittle Communications had reportedly lost $20 million last year, its first loss ever. Further, Whittle tried and failed to enlist potential investors in The Edison Project, such as Paramount Communications and Walt Disney Co., and one of its original investors, Time-Warner, pulled out. Whittle announced the Edison Project in 1991, originally promising to raise $2-3 billion to fund a chain of private schools.

He later amended that figure to $750 million and sought public school contracts. The Edison Project has been able to raise approximately $40 million for research and development, but no more. The project’s president, Benno Schmidt, has said Edison needs an additional $120 million as it moves into 1995 in order to begin implementing its plan.

At this point, the Edison Project is primarily a marketing venture long on promises and short on experience. For example, Schmidt claims that Edison schools will “achieve quantum gains in the academic achievement of students, in the quality of their lives and in the well-being of our nation.” Similar claims are made about their curriculum. For example, Edison says their economic curriculum “will offer a rare and sophisticated understanding of the world of business,” yet an Edison spokesperson admitted to Rethinking Schools that the curriculum does not exist. In fact, the Edison Project has only publicly released a curriculum that goes through third grade.

Edison’s marketing chutzpah was in strong evidence in Milwaukee, where it proposed that in addition to running individual schools, it sign a contract with the district “in support of efforts to implement School to Work.” Given that Edison has no schools, no school-to-work projects, and no published curricula beyond third grade, many found it hard to take the offer seriously. Jean Tyler, who co-chaired the district’s school-to-work task force and who heads up Milwaukee’s governmental watchdog Public Policy Forum, told The Milwaukee Journal: “The Edison Project knows nothing about school to work.”

The claim that for-profit firms hold the answers to educational problems is unfounded, especially given the history of for-profit schools in this country. The only arena where for-profit firms have a significant track record of running schools is in post-secondary education. A three-part series in The New York Times in February looked at for-profit post-secondary schools and found rampant abuse and an almost complete lack of governmental oversight, even though the schools are financially dependent on federal student loans.

The following from the first article, headlined, “Billions for Schools Are Lost in Fraud, Waste and Abuse,” gives a flavor of the exposé: “In the most dramatic cases in recent years, directors of for-profit trade schools and colleges have looted the budgets of these loosely regulated federal student aid programs to buy themselves Mercedes-Benzes, travel the world, subsidize a drug habit, invest in religious causes, or pay themselves million-dollar salaries.”

School Financing

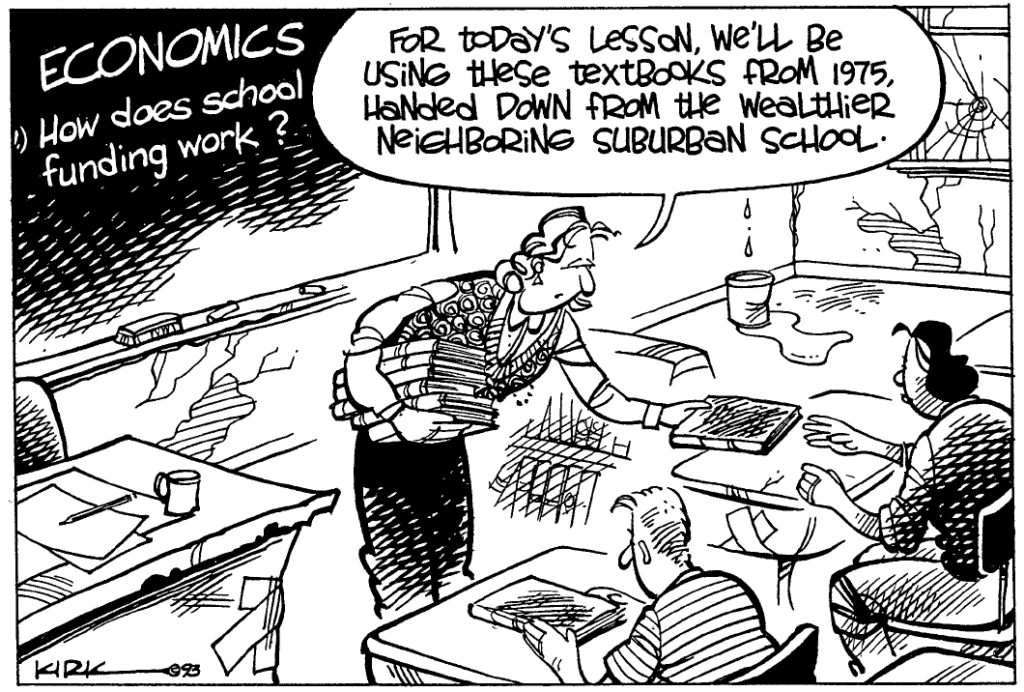

Despite the time and energy going into privatization schemes, it does little to resolve a major structural problem: the highly inequitable financing of public schools in this country, not only between suburban and non-suburban districts but from state to state. School finance reform was on the legislative agenda in many states, particularly Michigan and Wisconsin. In addition, in over half the states the issue of school finance equity is being battled in the courts.

Like charter schools, the school finance debate is extremely complicated. On the positive side, the debates recognize that relying on local property tax funding places undue burdens on “property poor” cities and rural areas. On the negative side, there is no guarantee that the property tax will be replaced with a more equitable system of financing — or that equity is even a major concern. In some legislative battles, the emphasis is on cutting taxes, not on adequately funding all schools.

Michigan made the most dramatic move this past year, with the legislature removing schools from the local property tax.

After a voter referendum, the state decided to raise money for schools via a 2-cent increase in the state sales tax. (Charter schools were also a key component in the reform package, and Michigan Gov. John Engler says he expects 200 charter schools up and running in the state within three years.) Several questions come to mind in regard to that Michigan reform: How stable is the source of funding? Will it significantly increase equity in Michigan? Will more state funding mean less local control? What are the repercussions of using a sales tax for school funding — a regressive tax disproportionately paid by low-income people?

Wisconsin was the second state to mandate reduced reliance on local property taxes to support schools. The alternative, however, has not yet been spelled out and the state is due for a year-long debate on how to resolve the controversy. Unfortunately, one proposal that has not been seriously debated is restoring certain business taxes and a more progressive income tax. (Overall, businesses provided approximately 33% of state revenues in 1960 through corporate income and property taxes. By 1990, the business share had dropped to 19%. Further, the top rate for individual income tax was 11.4% in the 1970s, but had dropped to 6.9% by 1987.)

The school funding legislation was a follow-up to spending caps passed in the summer of 1993 that essentially prohibited local school boards from increasing their budgets above the inflation rate — thus increasing inequities between districts and forcing a number of rural and urban districts to cut back basic programs.

Wisconsin Republican Governor Tommy Thompson found a few additional funds to provide a one-year increase in state aid to some districts — a move dictated by the gubernatorial election this fall. But Thompson’s record engenders little confidence that he or his appointees will develop a school financing reform that will decrease inequity and help impoverished rural and urban districts.

Unfortunately, the recent wave of federal education legislation basically did an end run around this central issue of equitable resources. The main legislation, Goals 2000: Educate America Act, focused on establishing national standards and, to the disappointment of progressive educators, failed to seriously address issues of equity.

Thus at year’s end, there were still more questions than answers in resolving the major policy issue facing public education: will there be adequate resources for all children and all schools?