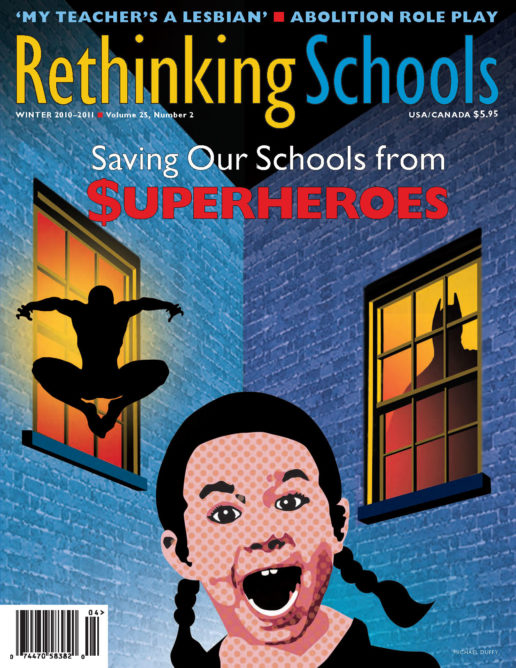

Preview of Article:

The Ultimate $uperpower

Supersized dollars drive Waiting for ‘Superman’ agenda

Illustrator: Michael Duffy

In 1972, two young Washington Post reporters were investigating a low-level burglary at the Watergate Hotel and stumbled upon a host of unexplained coincidences and connections that reached to the White House.

One of the reporters, Bob Woodward, went to a high-level government source and complained: “The story is dry. All we’ve got are pieces. We can’t seem to figure out what the puzzle is supposed to look like.”

To which the infamous Deep Throat replied: “Follow the money. Always follow the money.”

Sidestepping Democracy

For nearly 40 years, “follow the money” has been an axiom in both journalism and politics—although, as Shakespeare might complain, one “more honour’d in the breach than the observance.”

It is useful to resurrect the axiom in analyzing the multimedia buzz and policy debates swirling around the movie Waiting for “Superman.” In education, as in so many other aspects of society, money is being used to squeeze out democracy.

Waiting for “Superman” and its surrounding campaign reflect an influential trend that has proven adept at dominating education policy in both Republican and Democratic administrations. This bipartisan alliance unites 20th-century conservatives closely aligned with the Republican Party, who made the bulk of their money before the dawn of the digital era, and 21st-century billionaires more loosely aligned with the Democratic Party, who generally made their fortunes through digitally based technology. These two groups can be described as analog conservatives and digital billionaires.

Despite their differences, both groups embrace market-based reforms, entrepreneurial initiatives, deregulation, and data-driven/test-based accountability as the pillars of educational change. Under the banner of challenging bureaucracy and promoting innovation, both groups chafe at public oversight and collective bargaining agreements. Above all, both rely on money to get their way.