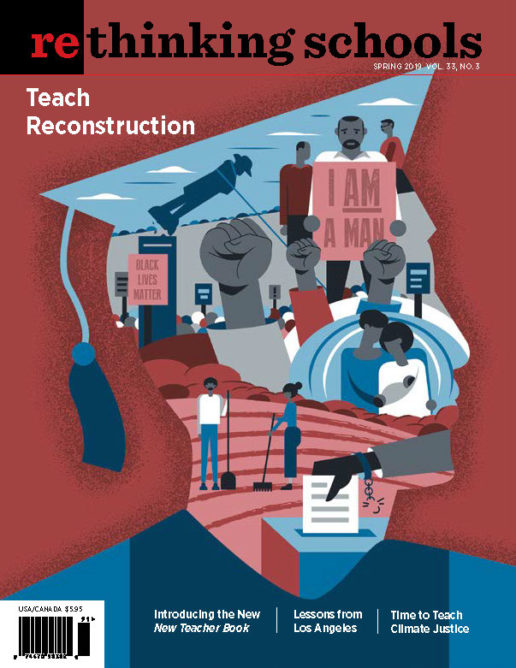

The School Formerly Known as LeConte

A debate in Berkeley about the power of a name

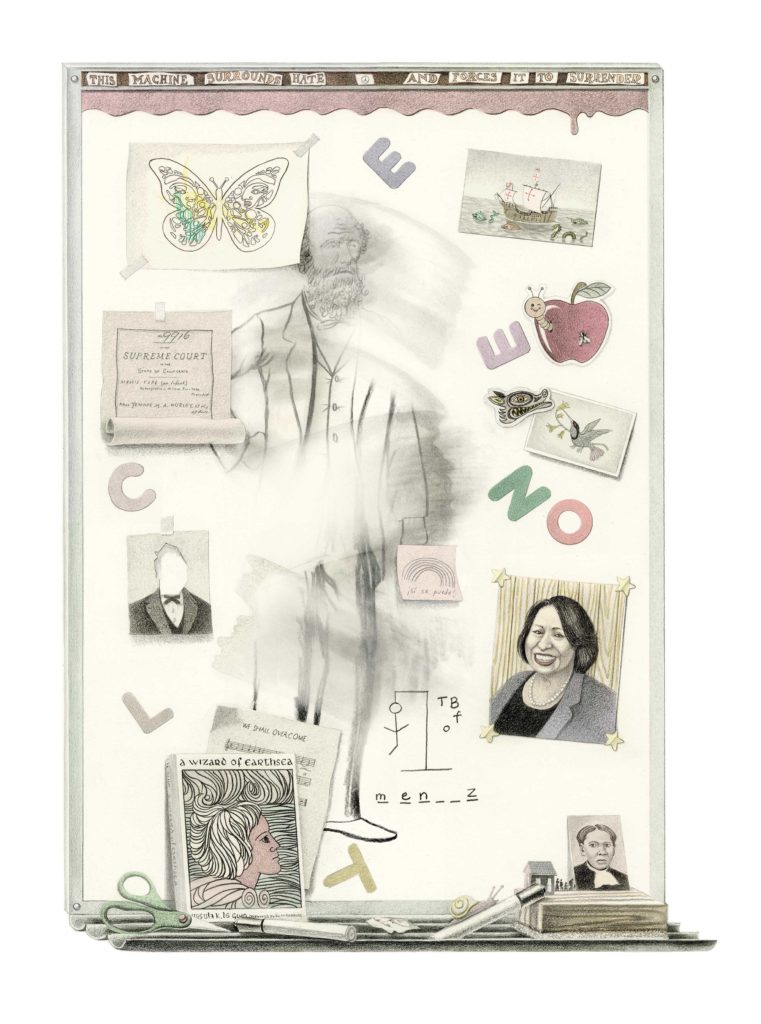

Illustrator: Armando Veve

At the first meeting gathered to rename LeConte Elementary School in Berkeley, California, committee members shared stories of their own names: where did they come from, and why were they thus named? Some said that their names were a way to honor a deceased family member or to pay homage to a cultural hero; for others, names were a part of their heritage.

Months before, the Berkeley community had decided that the LeConte name didn’t represent its values. Now the school renaming committee had assembled to discuss what made the school in question distinct from other schools. Who was that community, and if it didn’t stand for what the name LeConte had represented, what did it stand for?

Across the United States, we are toppling monuments and former heroes. Past icons are rightfully crashing — in esteem and in our public and private spaces — as we begin the overdue process of reckoning with history. Contemporary heroes are being lowered, too. This vogue of name controversies might be seen as a petty preoccupation by detractors, but what could be a more powerful symbol than what we choose to name a school?

A few years ago, Yale University swelled with protests and fraught conversations over Calhoun College, named after John C. Calhoun, a white supremacist. In 2015 Georgetown renamed buildings named after former school presidents who had orchestrated the university’s purchase of enslaved people. Also in 2015 the Black Student Union at UC Berkeley sent a letter to the university chancellor demanding that several buildings on campus, including one named after slave-owning brothers John and Joseph LeConte, be changed. “It’s hypocritical of UC Berkeley to name a building after Martin Luther King,” one of the BSU members told the school paper in 2015, “and then have buildings named after slave-owning racists and colonizers.”

Thanks to the Black Student Union, word of the LeConte provenance spread across campus and through the town of Berkeley. The Sierra Club had a mountain lodge named after LeConte; the name has since been changed. Just down the hill from UC Berkeley is LeConte Elementary School — or, as it was termed during the 2017-18 school year, “The School Formerly Known as LeConte.”

LeConte is a public, Spanish-English bilingual school nestled in a predominantly white, historically Black, and stalwartly progressive neighborhood near downtown. The school is so popular that it boasts a perennial wait list for its kindergarten class. It became clear to the vast majority of parents, staff, students, and community members that the school’s name was out of alignment with its mission and with the neighborhood where it stood. A group of parents, with staff consent, circulated a petition in May 2017 asking the Berkeley Unified School District Board of Education to consider a name change. On Nov. 15, 2017, the school board unanimously passed a motion to rename the School Formerly Known as LeConte.

The LeConte brothers came from a wealthy Georgia family that had lost much of its fortune as a result of the Civil War. In Joseph LeConte’s autobiography, he lovingly depicts the bygone days of plantation life — “a life that has passed forever. . . . It was, indeed, a very paradise for boys” — as well as his family’s early, bloody battles with native tribes. After the Civil War, his fortune diminished, and his former slaves were freed. Disgruntled by Reconstruction and “the iniquity of the carpet bag government,” as well as “scalawag officials and a negro legislature controlled by rascals,” LeConte sought employment at the newly formed UC Berkeley as a geologist and naturalist. His brother soon followed him. “The sudden enfranchisement of the negro without qualification was the greatest political crime ever perpetrated by any people, as is now admitted by all thoughtful men,” Joseph LeConte wrote in 1903, long after having settled in California.

It’s no surprise that more than a century later, the decision to rename Berkeley’s LeConte school came easily enough (this is Berkeley, after all). But the motion wasn’t the only end goal, merely a catalyst for a much more complicated community discussion: Now that the LeConte name was out, what would they name the school? The notion of renaming a building offers a clean slate, but it also requires a community to grapple with what they stand for rather than merely what they do not. It’s easy enough for Berkeley residents to insist that the city is not a place that honors slave owners; a much harder question is Who are we?

Ten years ago, renaming a school might have been considered a patently Berkeley preoccupation. (“That’s so Berkeley” is something that those of us who live here hear quite a lot from people who don’t.) Yet today, renaming buildings and tearing down old monuments is a national preoccupation, one of lifting something spectacular from the swamp of the past and taking the reins over the direction of the future. For the name we assign to a public space — a monument, a state building, an archway, a bench, a school — says something not just about who we are as a community but also what we aspire to become.

To name a building or institution after someone is an honor — one that, historically, was often purchased through endowments or the financing of the building itself. It connotes someone worthy of looking up to — quite literally, in some circumstances, as one walks beneath the name emblazoned on an archway or a door. To name a building after someone also anoints that person as a kind of hero, but a hero who, in the passing of time and the daily hubbub of the building’s use, can be forgotten or obscured. Was the dining hall at my private high school called Hill House because it was on a hill or because it was named after a wealthy person named Hill — or perhaps a person named Hill who had done something important, and grand, and worth naming this building after? I was never told; I never even wondered. Same goes in Berkeley.

This question — Who are we? — the board remanded to the community.

* * *

LeConte was not the first school in Berkeley to request a name change, and it certainly wouldn’t be the last. The Berkeley Unified School District developed a detailed, systematic renaming process a few years ago, partly in response to the name-change controversies sweeping the nation. The board had seen many of these renaming debates go awry. How could this renaming process be an opportunity for engaged community conversation, rather than coming to blows?

Board policy required the school to form a diverse committee comprised of neighbors, school staff, and parents. Under the leadership of Natasha Beery, the Berkeley Unified School District’s director of community relations, the district chose a committee of 10 members with three alternates (who ultimately became full-fledged members).

Beery had researched why the school had been named after LeConte in the first place. The year was 1892. Four schools were named that year: LeConte, Longfellow, Lincoln, and Columbus. (The last marked the 400th anniversary of his voyage — the explorer is another of history’s once gilded heroes who have rightfully fallen from grace.) Berkeley was a relatively young city, Beery explained, and it was defining itself, determining how it wanted to be seen. The process of choosing a name back then was a top-down affair, but then, just as now, what your community names its buildings “depends on what your aspirations are, how you want to be seen, and also who is at the table making the decisions.”

After considering their own names and the fundamental purpose of a name at the first meeting, the renaming committee put out an open call to the larger Berkeley community, which returned 118 names, a range of people and concepts so vast as to include Pete Seeger, Harriet Tubman, Ursula K. LeGuin (born and raised in Berkeley), Dreamer (a tribute to the struggles of young immigrants), the symbolic Mariposa (Spanish for butterfly), and In Lak’ech, a Mayan greeting roughly translated as “I am you, you are me.”

Each name would be discussed, considered, weighed. But how to choose who to lift up and who to cast aside?

The school board’s guidelines for choosing a name were so vastly inclusive that it hardly did much to narrow things down. They wanted names connected to:

1) individuals, living or deceased, who have made outstanding contributions to the community;

2) individuals, living or deceased, who have made outstanding contributions of state, national, or worldwide significance;

3) the geographic area in which the school or building is located; or

4) any other entity the board deems worthy of recognition.

Facilitated by committee member Grace Kong, a school parent, neighbor, and professional consultant, the committee came up with a guiding principle of eight considerations they found most important in a new name. They wanted the name to be inspiring, especially to schoolchildren, and enduring, likely to last even if the school or program changed or new information about the person surfaced down the line. They were looking for names that espoused the Berkeley values of equity, inclusion, social justice, diversity, arts, and science; ideally the name would have some sort of local connection as well. It would also be good to have a name from a community underrepresented among Berkeley school names; given that it is a bilingual school, they wanted some resonance with the multicultural mission. Also a plus would be a connection to education. The final consideration was underrecognition, or choosing a name not already widely used — or even known — across the United States. To hit all of these criteria was nearly impossible, but this list of qualities they were looking for in a name helped guide the committee.

The work wouldn’t be easy, that was clear. On the one hand, some of the groups’ biggest fears were that the naming process would occur along divisions of race or gender: Black people would want a Black hero, Latinos would want a Latino hero, women would want a woman, and so on. The conversations would very likely wade into difficult, fraught territory, explained Beery. On the other hand, she said, the committee wanted to be sure that they didn’t avoid these uncomfortable conversations.

“Maybe the only gift the current president has given us is that it’s brought to the surface things we’ve been looking away from,” Beery said. “I don’t want us to look away from history or from confronting our pasts. But at the same time we need to do it in a way that makes our community stronger, and includes our children. I don’t want this renaming process to be merely virtue posturing or political.”

Virtue posturing can be difficult to avoid in Berkeley. This is a place where people bicker on the ballot about whether or not we should pay additional taxes for the goats to chomp our hillsides for fire prevention. For years a core group of activists has been dedicating their weekends to stalling the city’s sale of the local post office (the experience of trying to mail a package is like a cross between a Woodstock revival and the trenches of World War I). Once, a vegan activist temporarily shut down a panel of environmental activists so that he could shame the panelists — and the rest of us in the room — for calling ourselves environmentalists while continuing to eat animal products. The energy is at once laudatory and occasionally eye roll-inducing; here, it seems, there’s always a fiery vegan (or the appropriate corollary) in the audience, boisterously out-lefting the people on stage. But while it’s a place where far leftism can be easy to mock from time to time, it is also a place so progressive that, like its neighbor San Francisco, it often has been a pioneer in critical social justice issues such as school integration, renter protections, and environmental divestment, to name a few.

* * *

Using their eight-point rubric, the committee began to whittle down the 118 names.

“Some people really connected to the Berkeley connection,” explained Kong, who facilitated the exceedingly complex committee discussions. “Others really were passionate about the underrepresented. But all gave us touchstones or reference points for our discussion along the way.”

Consider the conversation about Dolores Huerta, for instance. On the one hand, she is a Latina woman — no Berkeley schools were named after Latina women — and a leader who was heroic in her defense of migrant labor rights. On the other hand, though she is a hero in California, she wasn’t local to Berkeley or even to the Bay Area. Within the labor movement she was pressed to make compromises, including endorsing politicians who were, in some minds, the lesser of two evils, but an evil all the same.

Huerta is a hero, but “she’s not a saint,” said Steve Solnit, a BUSD parent and one of 13 on the committee. “On the other hand, this wasn’t a deification process.” Another consideration: dozens of schools and buildings in California already are named after Huerta.

Figuring out a name for a structure designed to exist for a long time always flirts with the edge of reductionism, tokenism, or the worse risk of naming a hero who turns out not to be so heroic after all. History, as in the case of Joseph LeConte, can wear away a hero’s luster. What if someone they named a school after ended up in a scandal like a #MeToo controversy?

There was also the issue of longevity. “We want a name that is enduring,” Solnit said. “We want a name that will matter in 10 years, not just a hero of the moment.”

Who gets to be considered a hero anyway? People of color are drastically underrepresented in our country’s school names, and we seem to recycle the same names again and again — Martin Luther King, César Chávez, Dolores Huerta. These are heroes of color, but choosing them again and again is its own kind of erasure. It’s also reductive, and perilously so, as if there are only so many people of color that we as a collective — or at least those of us with the power to name things — may deem worthy enough of heroism, and even, perhaps, see as “safe” enough, at this moment in time, to warrant a name. The power structures that be tend to prefer heroes who aren’t a threat.

“As someone who’s done a lot of work on LGBTQ history and rights,” said school board member Judy Appel, “I know that everyone always jumps to Harvey Milk; that’s the person everyone wants to recognize.” Harvey Milk is a hero, but still, Appel said of Berkeley, “When we name our first school after a queer person, I hope it won’t be Harvey Milk.”

Further complicating this desire to lift up underacknowledged heroes is that history can be buried deep. The School Formerly Known as LeConte sits on Ohlone native land, and many on the committee were interested in naming it after an Ohlone hero. But after centuries of genocide, Eurocentric narratives, and historic erasure, there aren’t many recorded heroes. Ohlone stories were not often written down and were not widely told. Plus, there was no Ohlone representation on the committee, and there can be a tension, as Solnit put it, between honoring and appropriating.

“It’s easy to see why in New York, they just name their schools numbers and leave it at that,” said Beery.

By February, the committee had a list of 20 names. By April, they had narrowed it down to seven: denise brown, a deeply beloved African American educator in Berkeley who had tremendous support from the wider community; the Tape family, who fought against school segregation in San Francisco and whose members had attended LeConte; Ohlone or a name related to Ohlone, the native people of Berkeley; Ruth Acty, an educator, an activist, and the first teacher of color in Berkeley Unified; labor activist Dolores Huerta; Sylvia Mendez, whose family fought to integrate schools in Los Angeles; and arcoiris, the Spanish word for rainbow, which had originally been suggested by a 5th-grade student at the school.

During the month of April, students read books about the seven finalists. For people who had not had books written about them, the school librarian researched and penned her own children’s books to share with students. Parents were encouraged to discuss the names with their children, and community members were invited to public forums to provide their feedback on the names. Meanwhile, Beery contacted the heirs or ancestors of the people under consideration to request permission. (“The rainbow didn’t seem to warrant outreach, though I would have loved to have tried,” she told the board.)

I attended the final board meeting in May where the committee announced its chosen name. The goal had been to present three names, but the committee had been nearly unanimous in choosing Sylvia Mendez, the little girl of Mexican and Puerto Rican descent whose parents fought to allow her entry into a white, segregated school in Orange County in 1943. Their 1947 legal victory forced all California schools to integrate thereafter, and the Sylvia Mendez case — though rarely discussed and largely unknown — was a critical precedent cited in Brown v. Board of Education, which would lead to school integration nationwide. After a presentation from the naming committee, the Berkeley school board unanimously approved the recommendation to change LeConte Elementary School to Sylvia Mendez Elementary School, and the whole room erupted into cheers.

“I am so proud of our students, staff, and community, who demonstrated that confronting our history can be done in a thoughtful, peaceful, democratic manner,” said Veronica Valerio, the school principal. “Our children will inherit this earth when we are gone, and after witnessing this process, I believe they are well prepared to lead it.”

The Friday before school started, I happily found myself acting as a de facto babysitter for a group of kids I’d never met before at a community event in Berkeley, hanging with the kids as their parents danced and drank wine. I asked a brother and sister whether they were excited about the beginning of school; he was starting 2nd grade, and she was entering kindergarten. Yes, they told me as they gobbled their Oreos, they were excited for school. I asked them which school they attended.

“Sylvia Mendez!” they both cried, in unison.

“She was a kid who helped make sure that different kids could all go to school together,” the brother explained.

I had wondered if it would take a while for the community to adjust to the name change, but their school’s new name and its provenance rolled off these siblings’ tongues easily, LeConte a distant memory: Bring on the future.

Sylvia Mendez Elementary School — the School Formerly Known as LeConte, which now has a name — opened that Monday.

Lauren Markham, based in Northern California, writes fiction, essays, and journalism. Her work has appeared in numerous national publications, including The New Republic, Guernica, and Vice, as well as on This American Life. Her book, The Far Away Brothers: Two Young Migrants and the Making of an American Life, was long-listed for a PEN America Award.

This article was first published in Lapham’s Quarterly.