Preview of Article:

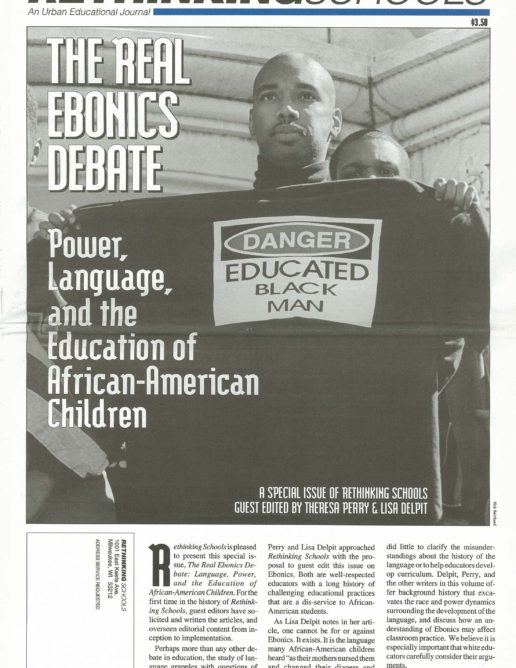

The Real Ebonics Debate

Power, Language, and the Education of African-American Children

Perhaps more than any other debate in education, the study of language grapples with questions of power and identity. We believe it is especially important that African-American educators take the lead in defining the discussion around Ebonics. We are pleased that Theresa Perry and Lisa Delpit approached Rethinking Schools with the proposal to guest edit this issue on Ebonics. Both are well-respected educators with a long history of challenging educational practices that are a disservice to African-American students.

As Lisa Delpit notes in her article, one cannot be for or against Ebonics. It exists. It is the language many African-American children heard “as their mothers nursed them and changed their diapers and played peek-a-boo with them. It is the language through which they first encountered love, nurturance, and joy.”

The national debate on Ebonics did little to clarify the misunderstandings about the history of the language or to help educators develop curriculum. Delpit, Perry, and the other writers in this volume offer background history that excavates the race and power dynamics surrounding the development of the language, and discuss how an understanding of Ebonics may affect classroom practice. We believe it is especially important that white educators carefully consider their arguments.

The authors in this issue, despite certain differences, have two essential points of unity: a respect for the language spoken by most African-American children — whether one calls that language Ebonics, Black Dialect, or an African-American Language System — and an understanding that African-American children must be taught Standard English if they are to succeed educationally. One of the media’s crudest distortions of the Oakland School Board’s resolution was the mistaken view that Oakland students would be taught Ebonics in place of Standard English.

How teachers view the home language of students and their families plays a significant role in teachers’ expectations and respect for a student’s culture. Speaking a different dialect or language, whether it is Ebonics, Spanish, or Tagalog, should not prejudice a teacher’s attitude toward a child. But too often it does. The difficulty is particularly acute for African-American students who speak Ebonics, because many teachers fail to recognize their language as anything other than a substandard form of English. As a result, they may view Ebonics-speaking children as stupid or lazy — although these value judgments might be couched in more acceptable terms such as “disadvantaged” or “in need of language remediation.”</p