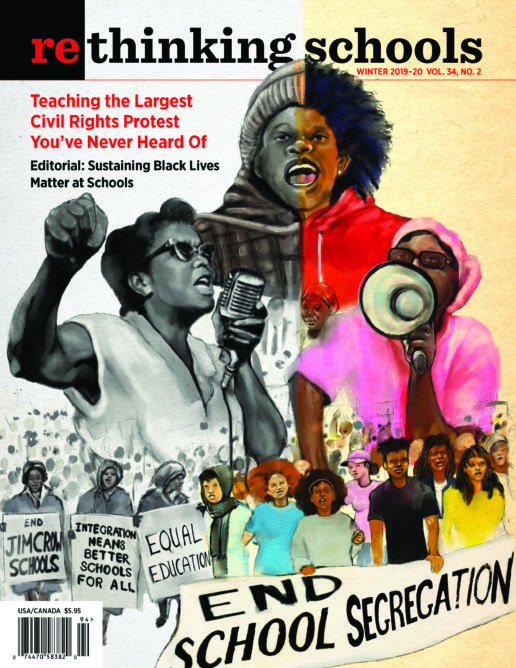

The Largest Civil Rights Protest You’ve Never Heard Of

Teaching the 1964 New York City school boycott

For the complete lesson plan and classroom materials that accompany this article, click here or go to bit.ly/CivilRightsProtestLessonPlan.

“Selma!”

“Birmingham!”

“Washington, D.C.!”

Struggling to remember their Southern geography, my students slowly rattled off cities that came to mind. I had asked them “Where did the largest civil rights protest of the 1960s take place?” Their answers, building off of the traditional civil rights narrative they had learned in elementary and middle school, mostly consisted of Southern cities. They were wrong. The real answer is New York City, where most of my students were born and raised.

This, of course, was no shock to me. Despite obligatory coverage of the Civil Rights Movement in every history textbook, I have yet to find a single K-12 textbook that mentions the boycott against segregated schools in which 464,361 students — about 45 percent of all NYC students at the time — stayed home from school. This demonstration was nearly twice as big as the March on Washington but is ignored in textbooks and most popular accounts of the movement.

The traditional narrative of the Civil Rights Movement tells a story of a movement that exclusively fought against racist laws in the South. This narrative reinforces the myth of progress, one in which most Americans, especially those in the North, responded positively to the demands of the Civil Rights Movement and righted the wrongs of lingering Southern racism. The movement, in this story, ends victorious when the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 strike down Jim Crow laws in the South. While these laws were momentous victories, they encompassed only a small fraction of the movement’s goals. Painting them as the fulfillment of the struggle against racism is a fable that ignores more than it reveals.

Indeed, when I was in school, I had also been taught the Civil Rights Movement as an exclusively Southern struggle, and so had been teaching it as such. I made efforts to complicate the traditional narrative — focusing on organizations like SNCC and complicating simplistic portrayals of national figures like Martin Luther King, Jr. — but for the most part the story my New York City students learned was a Southern one. This led to a disconnect my student Morganne expressed succinctly: “Before I knew that people in New York City were a part of the Civil Rights Movement I couldn’t see myself in the movement. It felt like everything happened in the South — and the West and the North were just sitting back and watching everything.”

The more I read about the Northern movement, from Thomas Sugrue’s Sweet Land of Liberty to Jeanne Theoharis’ A More Beautiful and Terrible History, the more I realized I needed to change my teaching to more accurately reflect the national Black freedom struggle and help students draw out its pertinence. The real Civil Rights Movement was not just about tearing down legal barriers, but about economic inequality, criminal injustice, police brutality, and access to quality education and healthcare. This movement was national in scope, led by young people, and confronted segregation and racism in both the North and the South.

Between 1940 and 1960, 2.5 million Black people and nearly 1 million Puerto Ricans migrated to New York City and found that most landlords refused to rent to people of color. The government maintained residential segregation in New York through a process commonly referred to as redlining. Neighborhoods were given an A to D rating. Ones with more than 5 percent people of color were given C and D ratings. This meant that homeowners or storeowners in Black or racially mixed neighborhoods could not get loans to update their property, leading to deteriorating conditions. At the same time, it encouraged white landlords and homeowners to keep out people of color for fear that their neighborhood might get a lower grade and deteriorate as well.

These government policies led to overcrowding in the Black and Puerto Rican neighborhoods and schools. Instead of redrawing the school boundaries to send students to less crowded white schools, the school board implemented part-time school days. When the board — under pressure from civil rights activists in the wake of the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision — finally attempted to bus some students to alleviate overcrowding, they faced fierce resistance from white parents. In 1958, when nine mothers in Harlem decided to keep their kids out of school to “demand a fair share of the pie,” the city decided to bring them up on charges for failure to send their children to school. By 1964, frustrations with the poor education Black and Puerto Rican students were receiving in New York led civil rights leaders to call for a one-day boycott of all schools. In the 10 years between the Brown decision and the boycott, segregation in New York City schools had quadrupled.

Though the boycott was a huge success — nearly half of all students in New York City stayed home that day — internal tensions within the coalition that had pulled it off led to its collapse in the following months. A second boycott about a month later was half as big and faced fiercer white opposition. That same month, more than 10,000 white parents marched to city hall opposing “forced busing.” With the coalition that had organized the initial boycott unable to repeat its success and white resistance on the rise, New York officials abandoned efforts to integrate schools. In many ways, the Civil Rights Movement was unsuccessful in places like New York City, leading to a deepening of some aspects of structural racism and segregation that exist to this day. Indeed, segregation in New York City has only gotten worse since the 1960s, and according to the UCLA Civil Rights Project, New York has “the most segregated schools in the country.” The history of the movement and its aftermath, therefore, is not simply a narrative of success. It’s a narrative that helps us understand the institutional racism that still exists today, because many aspects of racial injustice that the Civil Rights Movement fought against were never remedied.

Although I knew I couldn’t transform my curriculum overnight, I thought one good place to start would be to develop a lesson around what I thought was the biggest silence in the textbooks: the largest civil rights demonstration that none of my students — and few adults I’ve talked to — had heard of.

What Caused the 1964 New York City School Boycott?

After asking students to guess where the largest civil rights march of the 1960s took place, I revealed the answer. Students were shocked to learn that the city they lived in was where this demonstration took place and that they had never heard of it until 11th grade. With their interest piqued, I explained that in today’s class we would investigate why so many New York City students boycotted their schools in 1964. We began by reading together an excerpt from a New York Times editorial printed a few days before the boycott, titled “A Boycott Solves Nothing.” To set up the reading, I told students that “before getting a deeper understanding of what caused the boycott, we’re going to take a look at how newspapers at the time explained the action.” I told students that while they read, they should look for extreme language — words that exaggerate or leave little room for doubt or questioning. The New York Times editorial condemns the “reckless” civil rights leaders who are “hellbent on staging” a “violent, illegal,” “utterly unreasonable and unjustified” boycott, despite the school board’s well-meaning attempts to integrate schools. After we read the excerpt, we discussed the portrayal of civil rights leaders and students.

We discussed the extreme language the Times used to describe the boycott and I asked students whether they believed the New York Times editors that “reckless” and “unreasonable” civil rights leaders caused the boycott. Because the language is so over the top and because this lesson came in the middle of our unit on the Civil Rights Movement — which students are of course largely sympathetic to — all of my students seemed skeptical of the claims the Times was making. “They are just looking for a reason to frame them,” Morganne said. Grace concurred, “They are not trying to understand why the Civil Rights Movement leaders were launching the boycott. They are just playing sides.” Nicol argued, “They must be exaggerating to make the civil rights leaders look bad.”

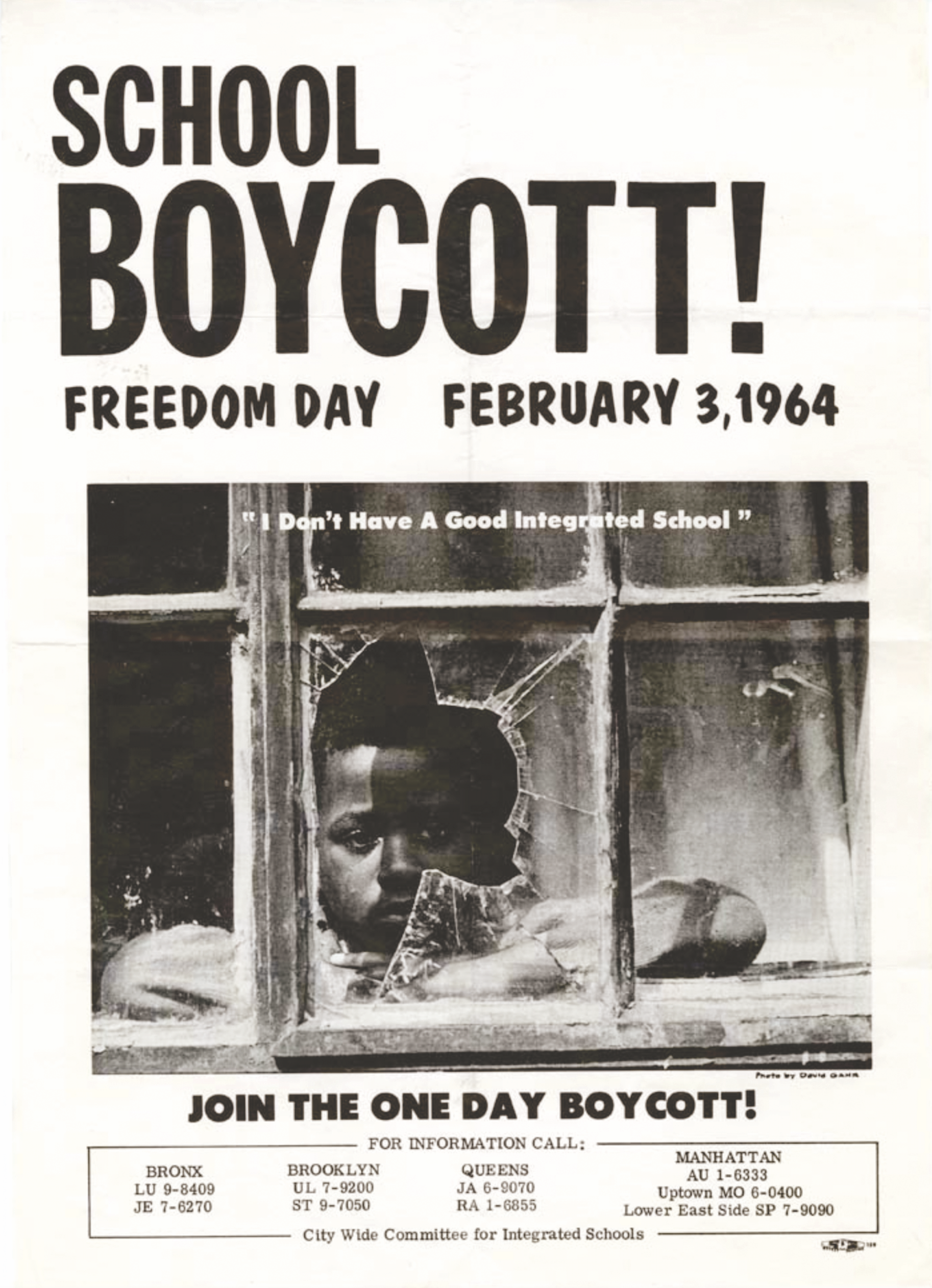

After our discussion I told students, “Obviously, the New York Times did not support the boycott. The media in the North was often dismissive of civil rights marchers in the North — even while sometimes supporting civil rights demonstrations in the South. So we need to take a deeper look into what was going on at the time to better understand why people decided to boycott schools.” I continued, “I will give everyone one clue that will help us answer what caused the NYC school boycott of 1964. Every clue is important. Start by reading your clue to make sure you understand it. You can explain your clue to the rest of the class, but you can’t show it to anyone else.” During the activity, I make an exception for the two clues that have images attached to them — which are useful for everyone to see.

I then distributed the “What Caused the 1964 NYC School Boycott? Questions” to each student. The handout has three questions to help students process the information they are learning during the activity:

1. What conditions outside of the schools made Blacks and Puerto Ricans in New York City angry?

2. What conditions inside of the schools made Blacks and Puerto Ricans in New York City angry?

3. What did school officials, Black, Latinx, and white New Yorkers do in response to the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision?

We reviewed the questions on the handout and I encouraged students to note which question their clues fit under and helped them if they weren’t sure. I explained the end goal of the activity would be to rewrite the New York Times editorial to be a more accurate explanation of why students boycotted NYC schools.

I facilitated by going through each of the three questions and asking, “Does anyone have a clue that speaks to this question?” One by one, students shared their clues as others took notes on the information they were learning. I’ll admit that this felt a little dry and too teacher-focused. I had worried that allowing students to just wander around the room and gather information would be too unstructured for some of my more easily distractible students and I overcompensated. In the future, I’d like to remove myself from the center of the activity. I plan to have students partner up to share their information and either rotate to a new partner after a set amount of time, or allow students to change their partners when they feel ready to move on.

As students explained their clues they learned about the various factors that helped push Blacks and Puerto Ricans to organize a mass boycott. One clue explains the policy of redlining. Another discusses the Board of Education oral examination that prevented teachers with “foreign” or “Southern” sounding accents from being hired as teachers. Another divulges the part-time school days the Board of Education implemented at overcrowded Black and Puerto Rican schools. The clues also provide information about the actions that people took before 1964. One clue tells about an early protest of 500 Black and Latinx parents led by civil rights activist Ella Baker, who complained, “They are always talking about poor people down South. And so the question was, what do you do about the poor children right here?” Another clue explains the small-scale integration plans the Board of Education did implement, while also acknowledging that segregation only worsened in the city despite those initiatives. A photograph clue, which I encourage students to pass around, depicts one of the early white protests of the Board of Education’s meager attempts at integration. Another clue tells the story of some of the white anti-racist activists who helped organize efforts for integration.

After we’d gone through all or most of the clues, I asked students to return to the New York Times editorial and re-write it. I had each student write their own editorial independently, but if I had more time for the lesson, I could imagine writing editorials in small groups being a worthwhile endeavor.

I told students, “You can imagine you are writing in response to the New York Times editorial, or simply for a different newspaper trying to tell the real story about what caused the boycott.”

Several students played off the New York Times title “A Boycott Solves Nothing.” Ethan titled his response “Writing an editorial doesn’t do much either.” Grace called hers “The Current System Solves Nothing.” Some students’ editorials focused on conditions outside of the schools. Gloria wrote, “Segregated housing, schools, and neighborhoods are angering Black and Puerto Rican New Yorkers. Housing segregation has led to overcrowding as more Black and Puerto Ricans migrate to NYC and are shut out of white neighborhoods through redlining.” Others focused on the problems inside the schools. Gabriela wrote, “Schools in Black and Puerto Rican neighborhoods have half-time school days due to overcrowding. Black and Puerto Rican students also face a lack of care from teachers and counselors — most of whom are substitutes. Teachers don’t want to work in these segregated schools.”

Some students responded directly to the New York Times editorial, playing off the first line that blamed civil rights leaders for being “hellbent on staging a Negro and Puerto Rican boycott” despite the “new Board of Education plan for better integration.” Ethan wrote, “A writer at the New York Times seems hellbent on downplaying the issues that many Black and Puerto Rican students face.” In her editorial titled “They’ve waited and they’re tired,” Gabriela argued, “The Board of Education’s new plan doesn’t matter . . . all their past plans have failed to integrate schools. In fact, schools are more segregated in 1964 than they were 10 years ago.”

From 1964 to Now

After writing the editorial, we read together a number of short documents that provided students with a picture of what happened after the 1964 boycott. The first document was a short excerpt from Matthew Delmont’s Why Busing Failed. Delmont details how one month after the boycott more than 10,000 white parents — mostly white women — marched on the Board of Education demanding an end to the small school pairing plan that would have transferred some Black and Puerto Rican students to predominantly white schools. The reading also details how these marchers influenced U.S. congressmen debating the Civil Rights Act at the time. Delmont argues that as a result of the march, congressmen, led by Brooklyn representative Emanuel Celler, wrote a loophole into the Civil Rights Act that “allowed segregation to exist and expand in Northern cities like New York, Chicago, and Detroit.” The Act’s Title IV, the section calling for the desegregation of public education, clarifies that “‘desegregation’ shall not mean the assignment of students to public schools in order to overcome racial imbalance.” By designating Northern schools as suffering from “racial imbalance” rather than “segregation,” the Civil Rights Act prevented Northern activists from accessing crucial legal tools to combat school segregation.

I asked students why they thought that Congress responded to the 10,000 white marchers and not the more than 450,000 boycotters. Sydney thought that maybe it was because Black people in the South couldn’t vote and so “they didn’t want to make white people angry, who were the largest group of voters back then.” Roger thought it was because “the New York Times reported the boycott as an unreasonable protest and covered the white marchers in a more positive light.” Ethan thought it was simply because congressmen “didn’t want to desegregate the North and believed the white marchers’ cause was more important.”

Next time, I plan to also ask students why they think the boycott failed and if there was anything activists could have done differently. I think it’s important for students to grapple with why one day of protesting — no matter how big — can sometimes be insufficient to create the desired change.

The next document we looked at was a series of graphs from an article titled “The Unmet Promise of Equality,” published in the New York Times in 2018. The graphs show how almost every region, except for the Northeast, saw a drastic decline in Black students attending schools with more than 90 percent minority student populations from 1968 to the early 1990s. I explained to students that a series of court cases in the 1990s began ending the desegregation plans that were put in place and forbidding further plans. But what every student noticed was that the Northeast never desegregated and in fact segregation in the region only worsened after 1968. As another graph in the article indicates, this means that half of the top 10 states with the most segregated student populations today are in the Northeast — with New York topping the list.

After discussing and clarifying what the graphs are saying, we looked at a series of headlines from 2018 that read: “Why Are New York’s Schools Segregated? It’s Not as Simple as Housing,” “Watch: Roomful of Rich, White NYC Parents Get Big Mad at Plan to Diversify Neighborhood’s Schools,” and “NYC Has the Most Segregated Schools in the Country. How Do We Fix That?” After looking at the graphs and the headlines, I asked students how learning about the 1964 boycott helps us understand what’s happening today. Ajonae exclaimed, “It’s like the same fights are still happening today.” Gabriela added that learning about the 1964 NYC boycott “helps us realize how long segregation has been a problem in this city. It encourages people to bring up the issue to our legislators so changes can be made.”

During the discussion, students also brought up their own personal experiences with segregation. Although I was teaching at one of the few integrated schools in New York City, many students felt like the lesson resonated with their experience at other schools. As Morganne stated, “My middle school was almost entirely Black. When I came to Harvest, it was exciting to go to school for the first time with people from all different backgrounds.” Grace reflected on her experience playing lacrosse at her former school in Westchester. “We would have tournaments over the weekends and teams from all across the nation would come and play. . . . It was rare for you to see any girl of color there. The culture of these tournaments was white and the sport was white dominated in general.” Next time I teach this lesson I want to add a debrief question that explicitly asks students to connect what they learned to their own experiences. I also want to think about ways to push students’ thinking beyond the segregation is bad, integration is good dynamic — to help them understand and empathize with why both during the Civil Rights Movement and now, some Black students, parents, and teachers see better-resourced Black schools rather than integration as the solution.

Nevertheless, some students were so struck by learning about the boycott they decided to write about it for their final class essay. Erezana’s essay helped confirm for me the importance of adding this lesson to my civil rights curriculum. She wrote, “The popular account of the Civil Rights Movement in the United States tells the epic story of a Southern movement born on a Montgomery bus and fortified in Mississippi jails . . . but this story leaves out many important events that happened in the North. . . . When we look at New York City, it is clear that the North was key to the Civil Rights Movement. We have to take a moment and realize the struggle that the North had and appreciate it because it was unsuccessful. This helps us understand why today New York has the most segregated schools in the United States. We are still dealing with what activists were fighting against in the 1960s.”

For the complete lesson plan and classroom materials that accompany this article, click here or go to bit.ly/CivilRightsProtestLessonPlan.