Teaching that Food Justice Is Racial Justice

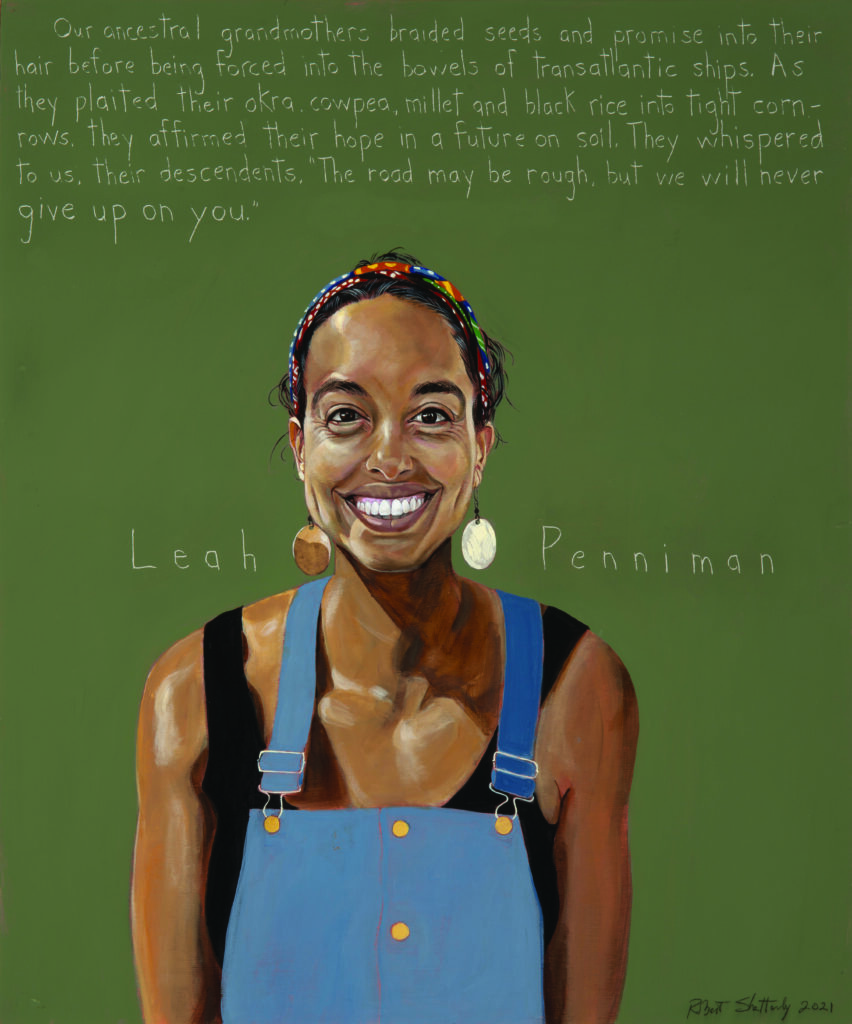

Photo courtesy of Naima Penniman and Soul Fire Farm.

I ‘ve been teaching about the politics and history of food in my social studies classrooms for almost 20 years, but for much of that time I was missing the stories of Black farmers in the United States. These stories raise important questions about the legacy of slavery in today’s food system, as well as highlighting the significant contributions of Black farmers to regenerative agricultural practices that are one of the best tools we have to address the climate crisis. I’m grateful to now have Leah Penniman’s voice and story to share with students.

I want students to come away from our study of issues like the climate crisis, racial injustice, and food knowing that it’s possible to confront problems in meaningful ways that can make material differences in people’s lives within our communities. At a time when students are overwhelmed by what appear to be insurmountable crises and social challenges, Penniman’s work as a farmer, activist, and teacher illustrates a tangible and compelling example that the solutions to these problems are already happening, if we’re willing to look for them.

Before encountering Penniman, I often ask students to describe what they think of when they hear the word “farmer.” Inevitably the conversation produces descriptions of a “white man in overalls and a straw hat,” “riding on a tractor” with a “piece of hay in their mouth.” The image is reminiscent of my own childhood memory of the ubiquitous Fisher-Price farm set that for most of my students — at predominantly white, affluent Lincoln High School in Portland, Oregon — seems not to have changed much in 50 years. The conversation offers a good opportunity to share with students that the majority of the world’s farmers are women of color (a fact highlighted in the La Vía Campesina role play in the Rethinking Schools book A People’s Curriculum for the Earth). This fact contrasts with farm ownership in the United States, where a hundred years of racist farming policies have resulted in only 1 to 2 percent of farms being Black-owned.

To introduce students to Penniman, I’ve used a short, excellent YouTube video How This Activist Farmer Fights Racism Through Food. In the video we see Penniman and others working the land and teaching interns at Soul Fire Farm in New York, which she describes as a “Black Indigenous community farm dedicated to ending racism in the food system and training the next generation of activist farmers.” Penniman’s smile and energy are infectious as she describes her personal journey to farming as a Black woman, the institutional racism inherent in our food system, and how Soul Fire Farm confronts this racism through building community food resiliency.

In one clip, Penniman describes the neighborhood in Albany where she and her partner lived with their young children, and how impossible it was to find fresh food. With only a convenience store, liquor store, and McDonald’s nearby, the neighborhood would usually be described as a “food desert,” but Penniman argues that because there’s nothing natural about the decades of segregation, redlining, and disinvestment that led to disproportionate levels of food insecurity in communities of color, that we should instead use the more accurate term “food apartheid.” The community garden that she and her partner started in the neighborhood as a response to this food apartheid became the first step toward eventually creating Soul Fire Farm.

After watching the video, I’ve asked students to read Leah Penniman’s piece, “Black Land Matters” (see below), and to keep a quote-response journal while they read. The reading opens with Penniman describing a field trip of teenagers to Soul Fire Farm, which feels like a natural hook to capture students’ interest. In the opening, Penniman also explains the associations she commonly hears from Black visitors to the farm between the land, soil, and slavery, making explicit the connections I want students to see between farming, food, and racial justice.

One student, Lucia, responded to Penniman’s essay with the following reflection:

I think it is really beautiful how Penniman has taken something that is a really big and scary problem and has enacted an effective solution that is rooted and driven by community work. I have never considered this specific relationship between Black Americans and farming, in particular how the history and legacy of slavery extends to something like farming. I think that the work Leah Penniman is doing to restore that relationship — which is damaged in a fundamental way — is really admirable and beautiful work.

Another student, Skylar, wrote:

Generational trauma has caused Black people to steer away from their roots, and practices that were brought by their ancestors when enslaved. Losing our culture is exactly what the white supremacist society wants. I believe that through education and empowerment, we will be able to rebuild this connection and continue our historic cultures and traditions, and Leah Penniman is proof that this is possible.

Penniman’s work brings to our students’ attention at least two key issues. The first is a reminder that humans are capable of nurturing healthy relationships with the earth — despite the litany of destructive human actions that we’ve come to accept as normal — and that many of our best teachers and examples of regenerative ecological practices come from Black and Indigenous communities.

The second theme that Penniman’s work underscores is that environmental justice is racial justice, and that issues as seemingly disparate as food insecurity, redlining, soil health, and Black agricultural traditions can be intricately connected in farming that is both a solution to food apartheid and the climate crisis. Through providing healthy, fresh produce to food insecure communities, by training the next generation of Black farmers, and doing it all in a way that restores and regenerates the health of the land, Leah Penniman’s work shows our students that tangible climate solutions exist.

Black Land Matters

By Leah Penniman

Dijour Carter refused to get out of the van parked in the gravel driveway at Soul Fire Farm in Grafton, New York. The other teens in his program emerged, skeptical, but Dijour lingered in the van with his hood up, headphones on, eyes averted. There was no way he was going to get mud on his new Jordans and no way he would soil his hands with the dirty work of farming. I didn’t blame him. Almost without exception, when I ask Black visitors to the farm what they first think of when they see the soil, they respond with “slavery” or “plantation.” Our families fled the red clays of Georgia for good reason — the memories of chattel slavery, sharecropping, convict leasing, and lynching were bound up with our relationship to the Earth. For many of our ancestors, freedom from terror and separation from the soil were synonymous.

While the adult mentors in Dijour’s summer program were fired up about this field trip to a Black-led farm focused on food justice, Dijour was not on board. It was only when he saw the group departing on a tour that his fear of being left alone in a forest full of bears overcame his fear of dirt. He joined us, removing his Jordans to protect them from the damp earth and allowing, at last, the soil to make direct contact with the soles of his bare feet.

Dijour, typically stoic and reserved, broke into tears during the closing circle at the end of that day. He explained that when he was very young, his grandmother had shown him how to garden and how to gently hold a handful of soil teeming with insects. She had died years ago, and he had forgotten these lessons. When he removed his shoes on the tour and let the mud reach his feet, the memory of her and of the land traveled from the earth, through his soles, and to his heart. He said that it felt like he was “finally home.”

Our Sacred Ancestral Relationship with Soil

Our 12,000-year history of noble, autonomous, and dignified relationship to land far surpasses the 246 years of enslavement and 75 years of sharecropping in the United States. As Black farmer Chris Bolden-Newsome explains, “The Land was the scene of the crime.” I would add, “She was never the criminal.”

Our ancestral grandmothers in the Dahomey region of West Africa braided seeds of okra, molokhia, and levant cotton into their hair before being forced to board transatlantic slave ships. They hid sesame, black-eyed peas, rice, and melon seed in their locks. They stashed away amara kale, gourd, sorrel, basil, tamarind, and kola in their tresses. The seed was their most precious legacy, and they believed against odds in a future of tilling and reaping the earth. They believed that we, Black descendants, would exist and that we would receive and honor the gift of the seed.

With the seed, our grandmothers also braided their ecosystemic and cultural knowledge. African people, expert agriculturalists, created soil testing systems that used taste to determine pH and touch to determine texture. Cleopatra developed the first vermicomposting systems, warning citizens that they would face harsh punishment for harming any worm. Ghanaian women created “African Dark Earth,” a compost mixture of bone char, kitchen scraps, and ash that built up over generations, capturing carbon, and fertilizing crops. African farmers developed dozens of complex agroforestry systems, integrating trees with herbs, annuals, and livestock. They built terraces to prevent erosion and invented the most versatile and widely used farming tool — the hoe. Our people invented the world’s initial irrigation systems 5,000 years ago and watered the Sahel with foggaras [underground water conduits] that are still in use today. They domesticated the first livestock and established rotational grazing that created fertile ground for grain crops.

Our ancestors created sophisticated communal labor systems, cooperative credit organizations, and land-honoring ceremony. On Turtle Island, Black agriculturalists like Booker T. Whatley, George Washington Carver, Fannie Lou Hamer, and Harriet Tubman brought us the CSA (community supported agriculture), organic/regenerative farming, cooperative farms, land trusts, and herbalism. Even as the colonizers pillaged the soil of 50 percent of its carbon in their first generation of settling, we used ancestral techniques like mounding, deep mulching, plant-based toxin extraction, and cover cropping to welcome life back into the soil. Our ancestral grandmothers braided all this wisdom and more into their hair and brought it across the Middle Passage. It is our heritage.

A New Generation

A new generation of Black farmers is using heritage farming practices to undo some of the damage first brought on by the intense tillage of early European settlers. Their practices drove around half of the organic matter from the soil into the sky as carbon dioxide. Agriculture continues to have a profound impact on the climate; along with forestry, deforestation, and other land use, it contributes roughly 24 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions.

Now Black farmers are using heritage practices to reduce emissions and to capture excess carbon from the air and trap it in the soil. Our ancestral strategies are bolstered by Western science and listed among the most substantive solutions to global warming, per Project Drawdown’s analysis.

One practice, silvopasture, is an Indigenous system that integrates nut and fruit trees, forage, and grasses to feed grazing livestock. Another, regenerative agriculture, involves minimal soil disturbance, organic production, compost application, the use of cover crops, and crop rotation. Both systems harness plants to capture greenhouse gases. Plants are nature’s alchemists, transforming atmospheric carbon dioxide into sugar and trapping it on the land where it belongs.

The soil stewards of generations past recognized that healthy soil is not only imperative for our food and climate security — it is also foundational for our cultural and emotional well-being. My teachers, the Queen Mothers of Odumase Krobo, Ghana, admonished, “How can it be that you Americans put a seed in the ground, and you do not pray, sing, dance, or pour libations and you expect the Earth to feed you? The Earth is a relative, not a commodity. That is why you are all sick!”

In every generation there were Black people who remembered the gift of the seed and the legacy of belonging to the land. We pay homage to one such rememberer, Fannie Lou Hamer, who said, “When you have 400 quarts of greens and gumbo soup canned for the winter, no one can push you around or tell you what to do.” In 1969, Hamer founded the Freedom Farm Cooperative on 40 acres of prime delta land. Her goal was to empower poor Black farmers and sharecroppers, who had suffered at the mercy of white landowners. “The time has come now when we are going to have to get what we need ourselves,” she said. “We may get a little help, here and there, but in the main we’re going to have to do it ourselves.” The co-op consisted of 1,500 families who planted cash crops, like soybeans and cotton, as well as mixed vegetables. They purchased another 640 acres and started a “pig bank” that distributed livestock to Black farmers. The farm grew into a multifaceted self-help organization, providing scholarships, home-building assistance, a commercial kitchen, a garment factory, a tool bank, agricultural training, and burial fees to its members. Thank you, Mama Hamer, for keeping the seed alive.

The seed is passed to us, Black children of Black gold. If we do not figure out how to continue the legacy of our agricultural traditions, this art of living on land in a sacred manner will go extinct for our people. Then, the KKK, the White Citizens’ Councils, and Monsanto will be rubbing their hands together in glee, saying, “We convinced them to hate the earth, and now it’s all ours.” We will not let the colonizers rob us of our right to belong to the Earth and to claim agency in the food system. We are Black Gold — our melanin-rich skin the mirror of the sacred soil in all her hues. We belong here, bare feet planted firmly on the land, hands calloused with the work of sustaining and nourishing our community.