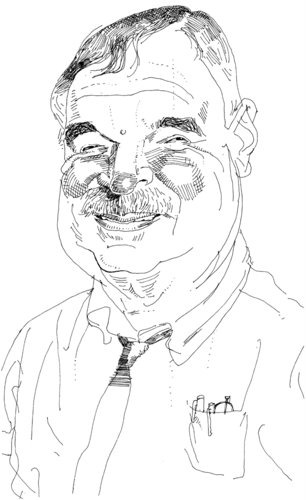

Teaching Is a Fight

An interview with Sal Castro

Illustrator: Joseph Ciardiello

In June, more than 40 years after the Los Angeles Unified School District tried to fire Sal Castro for his leadership of the 1968 Chicana/o Blowouts, it came full circle and named a middle school after him. As a young teacher, Castro was a key organizer of the 1968 student walkouts (called “blowouts” by the youth), when as many as 40,000 Chicana/o students marched out of their schools to demand bilingual and bicultural education, more Mexican American teachers and administrators, relevant curriculum, accurate textbooks, and an end to the tracking that steered Mexican American students into vocational classes.

Branded a dangerous agitator by television news commentators and charged with a series of felonies, Castro was fired by the school district. The community surged to his defense; eventually the charges were dropped and he was rehired. Through his work with the Chicano Youth Leadership Conference, Castro has nurtured generations of students. Since 1963, more than 5,000 students have participated in the conference.

In June 2010, Sal Castro sat down with Gilda L. Ochoa to talk about his passion for educational justice.

Gilda Ochoa: As a way to learn more about the factors shaping your perspective and work, can you begin by sharing a bit about your own family history and schooling?

Sal Castro: My parents came up here during the Mexican Revolution and met in Los Angeles. I guess they fell in love, got married, and I was born. When I was 2½–3, the height of the Depression hit; my old man got deported. They went to his place of work at the bakery—“Out you go.” And he was a legal resident. My mother was at home. If she had been at work at the laundry, hell, they would have taken her. He got sent back to Mexico, so then that started the unique process of my education in that we kept going back every summer because my mother had to keep her papers.

I began school at 5 years of age at Belvedere Elementary School in Los Angeles. But then, the next year, I went to Mazatlán, Mexico, in the summer, and I contracted the German measles. I had to stay there. My mother left me with my aunts. So my first formal school other than the kindergarten at Belvedere was a little private school in Mazatlán. When I was going to start school, they took me to the town carpenter. He measured me because they were going to build a desk for me to go to school, chair and all. I still remember those days there. They taught about people such as Cuauhtémoc, the last Aztec emperor, and the Niños Héroes of Chapultepec. They really loaded you up. It gave you a lot of pride. I was able to learn to read, and everything around me looked like family.

But then I come back to Los Angeles in the 2nd grade, and the teacher put me in a corner because I wasn’t as well versed in English as the rest of the kids. I was always challenging her—“How come I’m over here?”

I thought that she was the dumb one. Because she was older and bigger, she should have known Spanish. She should have been bilingual. I always put the onus on her. You know what happens to the U.S.-born kid, he puts the onus on himself, rather than the teacher. I always did the reverse. I guess that’s what made my education unique.

Ochoa: Why do you think you were so strong as a young child—able to realize that you were not the problem?

Castro: I guess that thing about the desk and the fact that I was successful in school early. Then I started being challenged, and I had to learn the language fast. It was the middle of World War II. There was rationing of food and clothing, and you couldn’t buy meat except with food stamps and little red chips, and you had to go to the school to get a new book of food stamps. I was the only one who could translate. I could see those people looking at us with disdain that my aunt didn’t know how to speak English.

As a little kid, I’d go shine shoes downtown at Clifton’s Cafeteria. I was supposed to take the money home, but then I’d go to the movies and buy popcorn. So, I’m sitting there at the Los Angeles Theatre. All of a sudden, the management turned the lights on for the sailors to come in and grab all the cholo kids and haul them out and either pull their pants off or cut them because they used to wear these drape pants. I ran out with my shoeshine box to see what the hell was going on, and I said, “Well, the cops will break all this up.” The cops stood there and laughed. I said, “Oh, shit!” and walked home. I was scared because you always think as a little kid, “The police are going to protect me.” But when they were part of it, I said, “Oh God!”

Becoming a Teacher, Joining the Fight

Ochoa: What made you decide to become a teacher?

Castro: I got a job working playgrounds. From that job with LA Rec. and Parks, I was able to also get a job with the school district in youth services. Working with the kids, I started thinking: “Man, this is cool. This is fun. These kids are crazy. They keep me crazy. I like kids and they respond to me, too.” At the time, I was a junior at Cal State Los Angeles, and I changed my major to social studies.

I started teaching in ’62 in Pasadena and then continued at Belmont High in LA. They liked what I did as a student teacher at Belmont, and they called me back for the fall of ’63. They wanted me to stay in Pasadena, but I said, “My fight is down there in LA.” I was already thinking fight rather than my teaching.

In fact, I first got into hot water at Belmont in ’63. I was there three months when I started figuring out, “There ain’t no Chicano kids in the student council.” Around 67 percent of the students were Chicanos, and there were no kids on the student council of Latino descent. They were just keeping them out. I also knew that there was a program at Belmont where a bus came, picked up 25 seniors, took them to City College to get college English credit. Not one of them was a goddamn Mexican kid.

I went to the principal and I told her, “You know, Mrs. Lord, more than half the kids are Latino, Mexican kids, and we’ve got no kids in any of the leadership positions or even this program.” She said, “Mr. Castro, the Mexican kid has a charming passivity, and you tell me you want to take that away?” I said, “Oh, shit, I’ve got problems here.”

So I started finding kids who were eligible to run for student council. I said, “Let’s form a political party to run as a slate.”

Two teachers helped me: Mary Mend and Pat Martin. I said, “We’ll all get together and create a constitutional convention to work out who’s going to run for what.” It was raining cats and dogs, but this school auditorium was filled, kids wanting to get involved. They picked the name: the TMs. They started writing the initials TM on the chalkboard of every classroom. TM stood for the Tortilla Movement!

There were speeches that would be presented to the school. I told the kids, “Say a few words in Spanish—just a sentence or so for the foreign students.” What I didn’t know, there was a rule at Belmont that there was not to be foreign language spoken on the stage. When the kids started speaking a few words, boom, they stopped the assembly. They made all the kids go back, and then they started drilling the kids. I said: “You want me. I’m the one that you want, not the kids.” The next day, I found myself suspended. The next semester, I found myself at Lincoln High School, just like that. I wasn’t even a probationary teacher. I was a provisional teacher, which meant I had no rights. How I survived that, I’ll never know. But they did transfer me to Lincoln, and I began all over again.

Ochoa: So you entered teaching with that perspective, knowing that it was going to be a fight.

How did this fit in with your involvement with the Chicano Youth Leadership Conference?

Castro: In ’63, when I was still at Belmont High School, there was an article in the paper about the LA County Human Relations Commission planning a three-day conference for Mexican American high school kids. They needed volunteers. The youth conference opened my eyes. You had 100 to 200 kids coming together from LA County schools, from as far as Pomona, El Monte, La Puente, West LA, the Valley. At the conference, kids were complaining about the same things all over. Kids were trying to survive—there was a fight between the girls about dying their hair blonde so they could fit in or pass. The kids were talking about the bathrooms being locked, the disrespect of teachers toward the kids, and so few students channeled to go to college. So much tracking was being done—the home economics tracking for girls and the industrialized arts for the boys. So, here we are saying, “Stay in school blah, blah, blah,” and they were mad.

I liked the fact that I was able to deal with kids from all around and exchange ideas about what could be done. But the main thing was that these kids had to graduate and go on to college. Any change that was going to happen, that’s the way it was going to be. So the conference continued every year, once a year. I kept going, kept in touch with the people, and stayed with it all the way through today.

Ochoa: So the Chicano Youth Leadership Conference had already started, and then in 1968 were the student walkouts.

Castro: It’s all one big package.

Ochoa: Can you tell me about your role in the walkouts and with the students?

Castro: The last straw was in April 1967. There was an article that came out in Time magazine called “Pocho’s Progress,” and they described East LA: “Rollicking cantinas with the reek of cheap red wine and greasy taco stands and the rat-tat-tat of low-riding cars down the avenue.” That’s how they described us! I started feeling a weight on my shoulders, like it was a barbell, and it kept getting heavier and heavier. The more I saw, the more I got into it, and the more I saw how really terrible the situation was. The minute the kids walked out, the weight went away, and I became cocky. I guess what I was supposed to do, I did.

Ochoa: In addition to the youth conference, what other organizing happened in preparation for the walkouts?

Castro: Everything came together. I started taking the kids from Lincoln High School to other places where we started meeting. We kept in contact with the kids from Wilson, Roosevelt, and a few other schools.

I thought we were going to bluff having a big strike, not doing it but bluffing it to the point that the school board would meet with the kids. Then the kids would give them the demands and say: “You either do it or we’ll clean out the schools. Kids are not going to go to school.”

That was the original intent because I was worried that kids crossing gang territories might be a problem if they walked out. I didn’t want anybody hurt. But just in case, I started going to colleges. UCLA was one of the first I went to. UMAS (United Mexican American Students) had already been created. I told them: “The kids are going to need you. They’re going to need you for your heads.” They looked at each other. “Well, I guess we’re the smart ones.” I said, “No, I need you to get your heads in the way in case the cops start swinging their batons; you’ll give the kids time to either run back to school or run home.” So they wholeheartedly supported it, as did students from other colleges.

The demands were real revolutionary ideas like smaller classes and more counselors. The papers made it seem like these were radical ideas. Today it’s called CRRE—culturally relevant and responsive education. That was what we wanted in ’68, but what do these Mexicans know?

The Chicano Youth Conference

Ochoa: How do you see the struggles we have faced since the walkouts?

Castro: When President Clinton invited me to the White House in the 1990s, I said: “My President, we’re in a crisis. We lead the nation in high school dropouts. We lead the nation in college dropouts, and we also lead the nation in the dubious distinction of teen pregnancies.” I could get invited to the White House again today and tell President Obama: “President Obama, you know what I told President Clinton 13 years ago? We still lead the nation in high school dropouts, college drops, and teen pregnancy.” Nothing’s really changed even though we’ve got more brown faces, a hell of a lot more brown faces, in positions that should do some good.

Ochoa: How has the Chicano Youth Conference tried to address educational disparities? Which students participate in the conference?

Castro: We’ve run one conference a year, sometimes two. We generally have about 150 kids from LA city schools, Valley schools, and parochial schools. Most of them are 11th graders, and some are 12th graders. We’ve had miraculous results from the kids who are doing poorly in school, and the kids who are doing well continue on—to the point that 84 to 87 percent of the kids who go through the three-day conference graduate from college.

Ochoa: What happens during those three days?

Castro: As the kids get off the buses in Malibu, high school mariachis are playing. Then they get broken up into groups of 10 with two college students. The groups are given Native American names such as Yaqui, Chippewa, and Zapotec. They’re in groups the whole time they’re there. On Friday, there are welcoming speeches and that evening they see the movie Walkout. They discuss it, and later on there is dancing. They learn how to polka so when they go to baptisms and weddings they’ll know how to dance. We keep them up until about 12:30-1:00.

We wake them at 5:30 with loud mañanitas music. A professor speaks. Sometimes it’s Dr. Rudy Acuña or Dr. Juan Gómez-Quiñones, so it’s been high-powered people. Not only do the professors talk about intellectual things, but there is also a lot of cultural and historical awareness.

Later on Saturday, they have a college fair. In the evening the college students become models with a fashion show on how to dress for the world of work. The kids go to a Mexican hoedown, and a conjunto from Santa Paula plays for them. At that point, the kids really come home. They dance the polka to the country music. We know that they’ve gotten the message when they start doing that. Later that evening, there’s a dance with a salsa band.

Sunday morning, there’s a mass and then testimony of what they’ve gotten out of the conference. Two or three kids from each of the tribes get up and speak about their experiences. Interacting with college folks and seeing all those PhDs really juices them. A lot of the comments when they leave are, “We didn’t know that there were that many PhDs, and we didn’t know that our people have done so much.” They walk out of there feeling 10 feet tall, and they’re very emotional. Boys and girls cry when they leave. They’re born again, born again Latinos.

The Role of Students Today

Ochoa: What role do you think today’s students should play in trying to effect change?

Castro: Last night when I was speaking at UC Riverside, the college students were telling me, “Hey, we want to go to Arizona.” I said: “Let the feds take care of that. Racism in this country has been going on since time immemorial. The changes will come by you getting a BA, an MA, a PhD. I want to see a room full of PhDs here. Go back to your schools, go and talk to the kids about college because you’re giants in the little kids’ eyes. Go set up field trips to bring the kids to the college. And you’ve got to get your degrees. This is the way that we’re going to eventually move forward.

Ochoa: So you told them to stay in school. But in 1968 people encouraged you to tell students not to walk out and you didn’t listen. Why do you think it’s different today?

Castro: They did tell us not to walk out. What do I think is different? For one, the money’s not there. Even though some of the things that we asked for were naive, they were things that could happen. Lowering the class size, having more college counselors, those were things they could do. Retraining so that teachers would have a different approach to teaching, there was even money for that. We asked for people in the community to work in the cafeteria and in the offices so there could be bilingual people. So most of the things were really not out of this world. It was affordable.

Today, we have these reactionary feelings that were dormant in ’68. One of the reasons why there’s a lot of resistance to allotting more money into education today is because white folks think that money is only going to be spent on minorities in schools, and they don’t want to spend their tax money on minorities.

In the late ’60s, there was turmoil, and there were folks out in the street not only for the Vietnam War but also for civil rights. The climate was ripe because there were attempts to change the path of where the United States was going. There was a hunger for redressing grievances and having the United States accomplish what it really was intended to do. Today, what these folks are talking about is a strict construction of the Constitution as they see it. They never once bother to see Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution that says the government is there to promote the general welfare. Does that not mean Medicare, Social Security, and education for all kids from K-16? To them, a government is there for protecting their individual liberty and nothing else. That’s the attitude today. There’s no way that you would get positive results [from student walkouts] from what people feel today.

The real obstacle is the racism of this country. If racism were eradicated then we really would have liberty and justice.

The Role of Teachers Today

Ochoa: What would you say to today’s teachers, given the current conditions for Chicano/Latino students?

Castro: You start with the love of the kids, not the love of your subject matter. You start loving the kids, and know that you’re going to go to the wall for them to make sure that they’re successful. Then, you better reek of ethnic studies. In history, you talk about the American Revolution, and you throw in Mexican or Spanish surnames: Bernardo Gálvez, the 9,000 Mexican troops that came up here, the money that Mexico donated to Washington for the revolution, the missions that were collecting money for the revolution.

The kids knew I cared. They knew that I was there for them even if they had already graduated. They saw the love. So they had respect for me.

Ochoa: You’ve had a long commitment to teaching.

Castro: Thirty years ago, I had offers from UCLA, Cal State Northridge, and other colleges. But I said: “No, no, I started as a teacher. I raised hell as a teacher.” Once, in 1975, they wanted me to run for Congress. NEA was going to finance it. But when I realized I would have to go out and beg for money I said, “Nah, I’ll beg for money for the kids,” which I do for the Chicano Youth Leadership Conference, but not for myself. So I backed out. I said, “I started as a teacher, and they may have to drag me feet first out of the classroom as a teacher.”