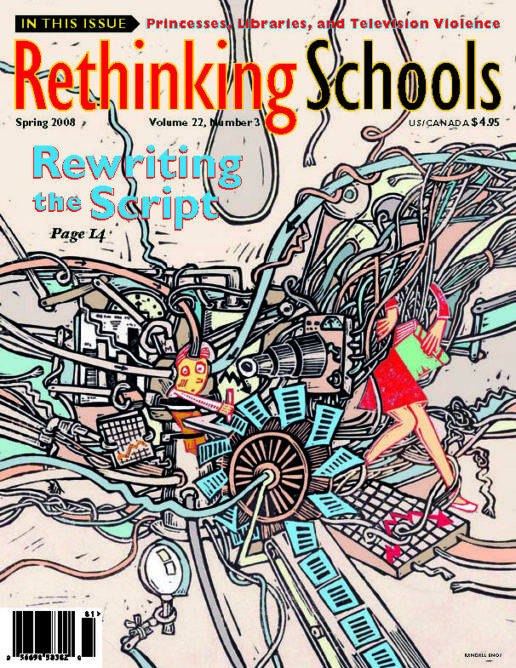

Teaching in Dystopia

Illustrator: Rob Dunlavey

We are being tested to death.

According to Peter Sacks, author of Standardized Minds: The High Price of America’s Testing Culture and What We Can Do to Change It, adults and children in the United States took as many as 600 million standardized tests both inside and outside of schools annually in the 1990s.

And this was before No Child Left Behind (NCLB) was passed in 2002.

The Education Sector, an independent think tank, reports that an estimated 45 million high-stakes, standardized tests are currently required annually under NCLB alone. Education Sector further estimates that states that have not fully implemented NCLB’s testing requirements will have to administer 11 million new tests in reading and math to meet federal mandate, with another 11 million new tests needed when and if science is added to federal requirements.

There is no mystery to how we arrived at today’s testing dystopia. The 1983 publication of the Reagan Administration’s report on education, A Nation At Risk: The Imperative for Education Reform, set the trajectory for 25 years of education policy. It sounded the alarm alleging the poor quality of education throughout the United States, equating it with a threat to national security.

Despite the fact that it was thoroughly debunked, within a year of this report being unleashed on the United States, 45 state-level commissions on education were created, and 26 states raised graduation requirements. By 1994, 45 states implemented statewide assessments for kindergarten through 5th grade.

The march toward federally mandated high-stakes, standardized testing continued through to the presidency of George H. W. Bush. His Summit on Education, held with the U.S. governors, became the groundwork for his America 2000 plan — focusing on testing and establishing “world class standards” in schools.

Even though it may have been birthed with Reagan and Bush Sr. in office, this push for high-stakes, standardized testing has always been bipartisan. Bill Clinton and Al Gore committed themselves to following through on the goals established by George H. W. Bush, maintaining the rhetoric of the necessity of “tough standards” in our schools and pursuing a national examination system to meet those standards. By 2000, every state but Iowa administered a mandated test.

So here we are in 2008, and soon NCLB will require elementary, middle, and high school students to take over 65 million high-stakes, standardized tests a year in public schools.

The problem is this: Testing is killing education. Not only is it narrowing the curriculum generally, it promotes bad pedagogy, while making some private companies very rich in the process.

Nationwide, the research surrounding the tests is fairly conclusive: High-stakes, standardized testing is narrowing the curriculum and encouraging bad pedagogy. A 2003 nationwide survey completed by researchers at the National Board on Educational Testing and Public Policy reported that 43 percent of the respondents from states where high stakes were attached to the tests said that a “great deal of increased time” was being spent on tested areas.

Similarly, a 2006 report on a nationwide survey completed by the Center on Education Policy (CEP) found that 71 percent of the districts studied cut at least one subject to increase time spent on reading and math as a direct response to the high-stakes testing mandated under No Child Left Behind.

As one Colorado public school teacher puts it, “Our district has told us to focus on reading, writing, and mathematics. Therefore, science and social studies

… don’t get taught.”

While test supporters may laud these increases in time spent on tested subjects, the reality is that such increases also represent a loss, because when it comes to high-stakes testing, the curriculum is a zero-sum game: Test-induced increases in math and English/language arts instruction come at the cost of reductions in other subjects.

In their 2007 study, for instance, the CEP reports that NCLB’s testing has resulted in an average weekly loss of 76 minutes of social studies instruction, 75 minutes of science instruction, 57 minutes of arts and music, 45 minutes of recess, and 40 minutes of physical education.

Low-performing students and students of color feel the zero-sum curriculum particularly sharply. As the CEP reported in 2006, in some districts in California the lowest performing students have had to take extra classes in reading and math, which has meant that these students have had to completely cut science and social studies from their course load.

In this same study, the CEP found that 97 percent of high-poverty school districts, which are largely populated by non-white students, have instituted policies specifically aimed at increasing time spent on reading. This is compared to only 55 percent to 59 percent of wealthier, whiter districts.

In this way, instead of improving the educational experiences of low-income students and students of color, NCLB and its focus on high-stakes testing create more restrictive, less rich educational environments for the very students proponents claim to be helping.

The logic of the zero-sum curriculum in the era of high-stakes testing is simple. If it isn’t on the test, chances are, it is less likely to be taught — especially in low-performing schools and districts. The problem is, such logic guarantees that our children are studying less about history and society, less about science, less about physical fitness, less about art and music, let alone issues of social, cultural, or environmental justice.

To add insult to injury, the subjects that are being taught within our testing dystopia are ultimately being ruined because the high-stakes tests push teachers to use bad pedagogy and teach more meaningless content. For instance, in a 2003 nationwide survey, researchers found that 76 percent of the teachers in states with high-stakes testing and 63 percent of the teachers in their study from states with low-stakes testing reported that their state testing programs were increasing teacher-centered pedagogies, rote memorization of materials, and lecturing.

As one Massachusetts language arts teacher commented in response to the effect of their state tests: “You know, we’re not really teaching them how to write. We’re teaching them how to follow a format…. It’s like… they’re doing paint-by-numbers.”

As infuriating as it is to see how high-stakes testing is negatively affecting all teachers, the research on its impact on newly credentialed teachers is particularly disheartening.

Arthur Costigan, assistant professor of education at Queens College CUNY, found in his research that the tests became the focus of the new teacher’s first year of instruction, that this type of teaching was having an adverse effect on their students and their practice, and that teachers developed a sense of powerlessness in the face of the amount of testing and the pressures involved.

Many of the teachers in Costigan’s study felt that “a very real culture of testing has been created in the schools and districts in which they teach…” and that they were “unable successfully to negotiate between a testing curriculum and personal best practice.”

The culture of testing negatively affects young teachers of color as well. In one case an African American teacher who recently graduated from her teacher education program was studied by Jane Agee, assistant professor of Language and Education at State University of New York at Albany. This teacher entered the profession proudly, with the expressed goals of teaching multicultural content in her classes, teaching in ways that would help her students of color succeed, and becoming an agent for positive change in her school.

In response to the mounting pressures of the high-stakes tests, however, this young African American teacher gave up her more activist and equity-minded goals in order to teach to the tests.

And this is one of the real tragedies of high-stakes testing. The first years of teaching are oftentimes precarious as new teachers focus not only on how to manage their tremendous workloads, but also on figuring out just what types of teachers they want to and can be. It is the time when they are developing their professional habits and their identities as teachers.

However, the tests are choking off the aspirations of our new teachers, dulling their sensibilities about how to best educate children before these sensibilities even have a chance to be nurtured and developed.

While we may be tested to death, private corporations are making a killing from our suffering: Continued compliance with the testing requirements of NCLB only means that more states will offer more tests, with increased profits going to select firms. Eduventures Inc., a private firm in Boston that offers its data analysis services to help companies “stay abreast of market trends, evaluate new markets and product lines, and better understand their customers” in K-12 and higher education, estimated the total value of the tests, test-prep materials, and testing services market in 2006 in the United States to be $2.3 billion.

Eduventures Inc. also estimates that the market created by NCLB-related test development, publishing, administering, analyzing, and reporting during the 2005-2006 school year alone was worth $517 million, with 90 percent of the revenues generated by statewide testing being collected by only a few companies, including Pearson Educational Measurement, CTB/McGraw-Hill, Harcourt Assessment Inc. and Riverside Publishing (a subsidaries of Houghton Mifflin Co.), and the Educational Testing Service. (The fact that a corporation such as Eduventures Inc. even exists is a sad testament to the growing marketization of public education.)

Amidst the avalanche of dollar signs, profits, and expanding “educational markets,” two simple realities are sometimes lost. First, a handful of large corporations are becoming the curriculum corporation of America, as schools and districts increasingly rely on them for test-oriented textbooks, instructional programs, and test-prep materials. Through the tests, these companies are essentially driving our curriculum. Second, most of the monies flowing to these companies are tax dollars, earmarked for public schools, now being funneled directly into the coffers of private industry. It is a shift in the power of corporations to control education that is happening under the guise of accountability and equality.

Every day, teachers enter their classrooms and try to make education meaningful for their students as well as fulfilling for themselves as teachers. Increasingly, however, our classrooms and schools are becoming testing dystopias where our abilities to effectively teach children are being distorted and marred by high-stakes testing.

Meanwhile, politicians on both sides of the aisle and supporters of NCLB continue to uphold high-stakes tests as the cure for what ails education. The problem is, their cure is killing us. The tests drain precious resources from public schools. They suck the life out of the curriculum. They promote bad pedagogy. It’s time to kill the tests before they kill education.