Teaching for Climate Justice: My Top 10 List

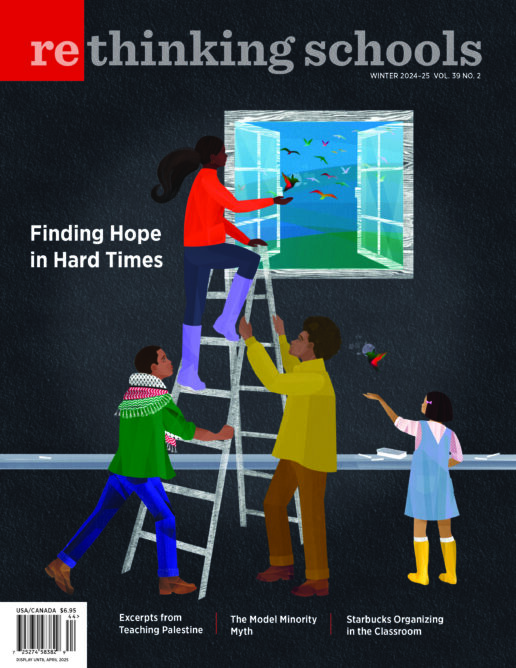

Illustrator: Joe Brusky

The first article that Rethinking Schools published about the climate crisis was in 2002, Bill McKibben’s “Global Warming: The Environmental Issue from Hell,” in Bob Peterson’s and my book Rethinking Globalization. Back then, not all teachers and students were convinced that climate change was real — “the science is sound,” McKibben felt compelled to assert in his article.

As I write, Hurricane Beryl is ravaging Texas, and for the past week temperatures have hovered around 100 degrees in my home of Portland, Oregon, yesterday hitting 104. I hate the phrase the new normal, because it sounds like we accept the unacceptable, but at this point, we need to acknowledge that the climate emergency is a permanent fact of life. Permanent, but not unchangeable: How activists and educators respond to the unfolding crisis will determine the quality — and the fairness — of life for generations to come.

These days, “climate justice” gets thrown around as if we all know what we mean by it. My friend and colleague Mimi Eisen teases me that I am an honorary millennial, as I like to structure articles in list formats, which Mimi tells me is a millennial thing. Because “climate justice” is so frequently used and mangled, I offer here my top 10 elements of a climate justice curriculum:

1.

We must teach the climate crisis not as a product of greed, bad corporations, or overconsumption, but of the capitalist system itself. When we think about the deafening silences in the mainstream curriculum, one of the most significant of these is the failure to teach young people to think systemically. Blaming greed, corporate malfeasance, or a lust for stuff may feel righteous and defiant, but it does not equip students to think intelligently about the profit system whose inevitable consequence is climate chaos.

2.

Central to climate justice teaching is equipping students to understand environmental racism. Zambian climate activist Veronica Mulenga puts it succinctly: “Historical and present-day injustices have both left Black, Indigenous, and people-of-color communities exposed to far greater environmental health hazards than white communities. Those most affected by climate change are Black and poor communities.” Whether it is whose voices we include in our curriculum, whose lives and which regions we focus on, or how we analyze climate consequences and potential solutions, we always need to probe how racism is implicated.

3.

A climate justice curriculum focuses on the historic roots of the crisis in colonialism, slavery, extractivism. Mimi Eisen and Ursula Wolfe-Rocca underscore this curricular imperative in the title of an important article: “The Climate Crisis Has a History. Teach It.” The seeds of the crisis can be found at least as far back as Columbus’ arrival in the Americas and his extractivist orientation that regarded everything, whether alive or inanimate, as a potential source of wealth. When students know this history, they can recognize patterns of power that continue to shape the climate crisis — and that need to be challenged.

4.

Climate justice takes an internationalist approach. It focuses on the impact of the crisis throughout the world — as well as the activist response. One of the first lessons that I developed about the climate crisis was a mixer that featured stories from people around the world who were affected by climate change — mostly people who were hurt by the changing climate, and often taking action, but some who were beneficiaries or part of causing it. In the first group of high school students I taught this to, one girl wrote that she was surprised that “people from all over the world are being affected.” It is crucial that a climate justice curriculum be a curriculum of global solidarity: The life of everyone in the world counts.

5.

A climate justice curriculum critiques individualism as a solution to climate chaos. Young people learn early to think about individual solutions to solve social and environmental problems: recycle more, drive less, take shorter showers, buy local, reduce your carbon footprint. As personal virtues, these are admirable. As a strategy for confronting the gathering climate emergency, they are useless. A climate justice curriculum not only avoids the promotion of individualism, it also explicitly critiques false solutions promoted by those whose interests are threatened by more radical and effective measures.

6.

Instead, students learn that meaningful social change is the product of social movements. A key question a climate justice curriculum addresses is: How do societies change? Change is not made by elites with a stake in the relations of wealth and power that keep them at the top. Nor is it made by the individual choices of consumers. A climate justice curriculum centers popular movements that have sought to transform social relations and make lasting change — from the abolition movement to the labor movement to the Civil Rights Movement. A climate justice curriculum needn’t always focus on the climate; exploring the means to collectively challenge injustice of all kinds also addresses the climate crisis.

7.

Climate justice teaching reaches beyond the immediate causes and consequences of climate change. Climate justice requires us to help students explore the intersection of a host of crises and issues that at first might not occur to people — the genocide in Gaza, Indigenous rights, labor activism, nuclear testing. As the Visualizing Palestine graphic “No War, No Warming” illustrates, the U.S. military is the world’s leading institutional fossil fuel user, with 48 million tons of emissions in 2022 — and Israel, the largest recipient of U.S. military aid, has an even higher per capita spending on the military than the United States. Not only has Israel’s war on Gaza resulted in unspeakable suffering, but the climate crisis compounds people’s misery: According to climate-refugees.org, Gaza suffers from “more frequent and increased cold snaps in winter months and temperatures rising 20 percent faster than anywhere else in the world.” The climate crisis touches — and is touched by — everything. We need to surface these connections with students.

8.

A climate justice curriculum is problem-posing, participatory, playful, critical. The “justice” piece of climate justice is not only about the content of the curriculum, but also concerns how we approach our students. Through role plays, simulations, critical reading and writing activities, and “make a difference in the world” projects, we need to respect them as intellectuals, capable of wrestling with all the historical, political, scientific, and moral issues embedded in the climate crisis. Climate justice must be pedagogical justice.

9.

Climate justice teaching happens in all disciplines, not just in science classes. In Portland, Oregon, when we launched our Portland Public Schools Climate Justice Committee in 2016, school district authorities immediately placed our committee under the auspices of the science administrator — without asking anyone on the committee. It was assumed that climate = science. And it does. But climate change is also a health issue. Social studies classes need to center the causes, consequences, and potential solutions to the crisis. Language arts classes should feature climate poetry, fiction, essays, personal narrative. Engineering, art, math, music — all disciplines “own” the climate crisis. Teachers need to challenge curricular silos whenever administrators force us to climb into them.

10.

To be a climate justice educator is to be an activist educator.We are part of a global community of climate justice educators who are not only reimagining our own classrooms, but who are reaching out to colleagues to invite them to join the movement. We can write, speak, tell stories, join webinars. But the most effective outreach to other teachers may be when we show, engage, model climate justice curriculum. Participants in our workshops need to say to themselves, “Ah, I see what this can look like.” Climate justice educators create space to imagine what this work entails in different disciplines, grade levels, and communities.

When I was in high school in the San Francisco Bay Area, I used to listen to Scoop Nisker report the news on KSAN radio. He ended every broadcast with “If you don’t like the news, go out and make some of your own.” The climate news these days is bad. As climate justice educators, let’s go make some of our own.