Teaching Debt Pollution in Schools

Like most students and workers drowning in the district debt crisis, I didn’t even realize a school district could be in debt until well after years of wading through its disastrous effects. The very air we breathe and water we drink as educators and students in School District of Philadelphia (SDP) buildings is polluted with indebtedness.

When I finally learned the role debt plays in sucking away nearly 10 percent of the precious little funding we have to work with, I had been in the SDP for more than 14 years, first as a student and then as a teacher. I was already teaching about school funding in my 10th- and 11th-grade civics class. My students and I were living and learning in starved conditions every day, and it was clear that part of my job needed to be helping kids fight back against the poverty-level budget of the SDP.

The Effects of Underfunding

During a unit on community organizing against discriminatory underfunding I asked, “What do you want to see changed in your school experiences? Write your answers on sticky notes and place them on the board.”

As students contributed, I asked a volunteer to move the sticky notes into categories — to group like problems together. There was a bucket around authority and autonomy (teachers who were “mean,” school cops who “yelled at them,” dress code rules they thought were unfair, etc.). There was a bucket around workload, homework, testing, and anxiety. There were other smaller groupings. But the largest bucket was underfunding: not enough counselors, teachers, cleaning staff, or extracurriculars. A lack of gym equipment or supplies of almost any kind. Terrible food with small portions. Unsanitary conditions — roaches, mice, bed bugs. Structural conditions — crumbling ceilings, defunct heating and cooling systems, high lead levels in the water, broken floor tiles, leaking roofs, leaking radiators, crumbling plaster, and the ever-present threat of wondering “Is that asbestos? Is this?”

Gesturing toward the whiteboard filled with sticky notes, I asked, “Looking at these problems, how many could be solved by providing the school with more money?”

“Mostly all of them,” said René.

“But they don’t care,” mumbled Kalin.

“But the district is always broke,” laughed Destiny.

Kalin added, “Ha, they’re not giving us money.”

“But why? Why aren’t they giving us money if it would immediately fix most of our problems?” I asked.

Next, I shared an overview of our district’s funding sources: $1.79 billion from city property taxes; $2.2 billion from the state; $16 million from the feds.

Many of my students didn’t believe me when I told them that not all school districts look as run down as ours. I showed them photos of schools in the suburbs.

Siyla said, “Those are like movie high schools. Like teen movie high schools where there is the popular kid and the nerd, and they end up dating at the end.”

“But they’re real,” I said. “My partner went to one. It had an indoor pool.” Luckily, a transfer student in the class had attended one of these mythical schools: “I played football for a school like that. They had showers that weren’t disgusting. And there was just so many windows. It was like you didn’t even need to turn the light on because it was always just so light in there.”

We zoomed in to the local level of funding via property taxes. Districts with higher property values generate more revenue than districts with lower property values. Poorer areas with higher need generate less money via property wealth, and areas with less need can generate more revenue. We contrasted the property tax revenue of SDP with Lower Merion, a Philadelphia suburb. After presenting the initial concept, I found that it was easier to understand with familiar neighborhoods in the city. Students helped me choose two neighborhoods in Philadelphia, Old City and Fairhill, one rich and one poor. I made up a two-part worksheet that asked students to imagine each neighborhood was its own school district and funded things through their own property taxes. It asked students to draw a school that might be found in each neighborhood and describe it.

Students shared their drawings. Some highlights of the Old City imaginings: Central air. A 3D printer. A gym not also the cafeteria. Buffet-style food, “like the movie high schools!” An elevator. Grass. Trees. A playground. Teacher assistants in every room. Lots and lots of windows.

The Fairhill school imaginings looked much the same as our own school. One student drew a school with a big sign on the front that said “permanently closed for funding cuts.”

To further explore the devastating effects of underfunding, we watched the film Goodbye to City Schools by Amy Yeboah, which follows four shuttered schools in the district in the weeks before they closed due to budget shortages. Through this personal and poignant portrait, students could see the community trauma caused when a school district closes schools to save money.

Then I gave students a list of the schools from the 2013 wave of closures and asked them to choose one to profile. “Look them up on Google Images. Figure out where they are in the city. See if you can find any of the students’ work or videos on YouTube. Pick one that you feel drawn to.”

Students had mixed reviews about the schools. “My sister went here, and this place honestly looked like it should have been condemned,” said René. “Anderson, this school had a major football team. How could they close their team like that?” wondered Maahir. “Look at this school, Anderson! It actually looks like it was nice. I would have rather gone there than here. Why would they tear this down? I don’t get it,” said Tahlee.

Students sought out alumni and former staff from their chosen schools and interviewed them on their experiences. They created comic books detailing the stories people shared. Finally, they produced detailed school timelines, digitally or on paper, showing the life of the school, with their interview placed in its chronologic place.

The Role of Debt in Underfunding

I discovered the debt piece of the district underfunding puzzle when a grad school professor assigned reading from a book called Carceral Capitalism by Jackie Wang. As I was reading the chapter, a passage jumped out. I read it twice to make sure I understood its implications:

[G]iven that government bodies are increasingly reliant on credit to finance their activities (as tax collection has not grown to keep pace with expenditures), a growing portion of revenue is going toward making payments to creditors. . . . [T]o maintain a good credit rating during periods when revenue is lagging, municipalities must fuck over residents by implementing austerity measures such as firing public employees, cutting pension funds and health care benefits, weakening the power of labor unions, cutting the education budget, and so forth.

Cutting the education budget to maintain a good credit rating? I knew that cities and countries could be in debt. Every time I went to vote, there was a question asking if Philadelphia should borrow more money in order to do x, y, or z. But I had not thought about how this might impact public institutions like school districts. I was baffled. Why should a school district have to borrow money for things that students and educators need?

I began researching the SDP and debt. Finding information was difficult — the district pages documenting the debt financing seemed intentionally cryptic. Slowly I compiled information, relying heavily on explanations from my more math-minded friends.

I wanted to pass the information on to my students so I put together a lecture-style slideshow:

Slide one: For more than 20 years, the SDP had a horrible credit score. Many of my students had a decent knowledge of credit scores, as their families are required to have good credit scores to rent housing. “School districts have credit scores?” Maahir was amazed. “Yes. This was news to me, too,” I replied.

Slide two: The crappy credit rating made it more expensive for the SDP to borrow money for regular building maintenance. Meanwhile, the state and feds weren’t helping to fill in the funding gaps. Buildings weren’t maintained and today the repairs needed are astronomical in price. “So that’s why everything is falling apart,” said Destiny.

Slide three: SDP pays up to 10 percent of its budget for debt service every year. This debt service takes priority over all other yearly expenses for the district.

Slide four: The district has four anchor goals, and was meeting only one of them — to end the year in a positive fund balance.

Slide five: The district planned to cut $38 million dollars in expenses for Fiscal Year 2021. “How are they going to cut money from us, but still find enough money to pay back those banks?” asked Tahlee.

Slide six: The banks are always guaranteed their money. Students and educators aren’t guaranteed anything — not even the most basic environmental safety measures. “I don’t understand how this is even legal.” Kalin was mystified.

After the slideshow, I said, “Find a gif or picture that represents how you feel when you hear the word ‘debt.’”

When I first ran this lesson, we were virtual. Subsequently I have tried having students draw images and stick them to the board. One student posted a gif of SpongeBob SquarePants digging a hole in the sand of Bikini Bottom, laying himself in it, and then burying himself back up under the sand. Another student posted a gif of Steve Harvey falling to his knees in tears. Another year in person, a student drew a picture of someone drowning in a flood.

I asked students if they noticed any patterns as they looked at the collection of images. “Dying.” “Scared.” “Crying.” During virtual school, a student typed into the chat “When you owe them something and you can’t pay, you can be homeless. They just take your house or things away if you can’t pay.” Although students might not have known the role debt played in underfunding within the district, it was clear they knew the devastating effects it can have on individuals.

To build on this, I created a Choose Your Own Debt Adventure game for students to work through in groups. Once inside the game, they chose a character. The first character’s story is about medical debt. Babette is a middle-aged woman who supports herself financially by selling crafts and cleaning houses for upper-class families. One day while out with friends, she trips and breaks her kneecap. She requires surgery but her insurance refuses to cover it. From that point on students have options to decide how Babette reacts to difficult financial and health decisions. In the end, no results are good for Babette. If she takes out loans to help pay for the surgery, she has to rush back to work to pay them off, which prevents her from healing properly. If she decides not to rush back and lets the bills pile up as she heals, she loses her car and has to move in with friends. If she decides never to take the money in the first place, she is permanently unable to walk.

After the game, I asked students to reflect. “What rationale did you use to make hard decisions?”

“We just wanted Babette to be happy,” said Destiny.

“We needed her to save the most money,” replied Kalin.

“What was the result? How could things have been different if Babette just had the money that she needed?” I pressed.

“It’s damned if you do, damned if you don’t. They get you either way,” sighed René.

“Everyone thinks you have things wrong with your body because you just didn’t take care of your health but that’s not it. It’s this. They get you like this. That’s why everyone is in wheelchairs,” Destiny said.

“We would have communities of thriving people,” added Maahir.

Some students shared their own stories of loved ones impacted by debt. One student described how their parents nearly broke up over a fight because their dad bought a car that the family couldn’t afford. When the payments were too high, they had to pay more in total to pay less monthly. “I didn’t know what it was about except that my mom was yelling she was tired of being in debt and he was trying to convince her that he had it under control.”

We then went on a photo scavenger hunt around the school, based on the question “What happens when a school district is forced to prioritize their debts over their students?” I prompted, “Look for things you know would be different if we had all the money that we need. Look for the things you know you deserve and aren’t getting.” I sent pairs of students out in the school to take photos of problems they thought could be solved with fair funding. Some of these included broken sports equipment, kids waiting their turn outside of the counselor’s office, crumbling ceilings, and a schoolyard filled with no trees or plants, just asphalt. When we came back to class, each pair shared what they took a photo of and why.

Their findings were validated in February 2023, when a landmark court case determined that Pennsylvania school funding is unconstitutional. Months of testimony provided by students and parents mirrored many of the scenes my students photographed that day.

After the photo scavenger hunt, I had students go back into the Choose Your Own Debt Adventure game, this time playing as the school district rather than an individual debtor. The player has a bit more choice in this scenario. The game starts out: The governor of your state has decided to slash your district’s state funding. The city is impoverished and unable to make up the difference. The federal government refuses to help. You don’t think you have enough money to open schools in September. You can choose to: 1. Fight back and demand more funding. 2. Take out a loan. 3. Find a way to cut the district budget so you can open. The results of some choices are clearly better than others, with the choice to continue fighting back ending in the least amount of harm to staff and students. Fighting back lands you with a lower interest federal loan, for which you pay less per payment. The second option, taking out the loan, lands you with a high-interest loan. Cutting the budget lands you with a high-interest loan, massive budget cuts, and a dead student. But similar to the Babette story, all options are a catch-22. All pathways lead to the district having to take out at least some amount of loans. The best the debtor can do is try to choose the path that causes the least amount of harm.

“Yo, F this game, Anderson. There is no way to win,” complained Kalin.

“Duhhhhh, that’s the point. It’s real life,” Destiny shot back.

We continued to discuss the game using these questions: What path did your group choose? What happened in your district? How did having to make these choices affect schools? What compromises did you have to make?

Tahlee exclaimed, “Damn, they really got the whole school district the same way they get your grandmom at the furniture store with the bejeweled dream dining room set!”

Many students were angry, and articulated frustration that there was “no other choice.” “I mean what would happen if they stopped robbing us of our money and just didn’t pay back those banks? What are they going to do? Arrest everyone that works at the school district? Arrest the superintendent?” demanded René.

I explained about state takeovers of school boards: When school district leaders demand too much humanity from their elected officials, they get replaced. But students were not buying that there was no other choice. “People don’t even know about this,” Kalin said. “How can they protest about it or try to stop it if they don’t even know it’s happening?”

Finally, in bold letters on the board I wrote: What would be different if the district had been given the money they needed from the state and feds instead of having to take out a loan?

Tahlee: “None of this ever would have had to happen.”

Pedagogy of Experience

The week I taught this lesson felt buzzy and hopeful; the overall class vibe was a sort of excited and weirdly positive anger. It felt like we were ready to do something. We started exploring different case studies of school communities fighting back against budget cuts, staging die-ins in toxic buildings, showing up to school in gas masks, organizing living-with-lead-and-asbestos safety workshops for the community, curating effects of underfunding photography exhibits, etc.

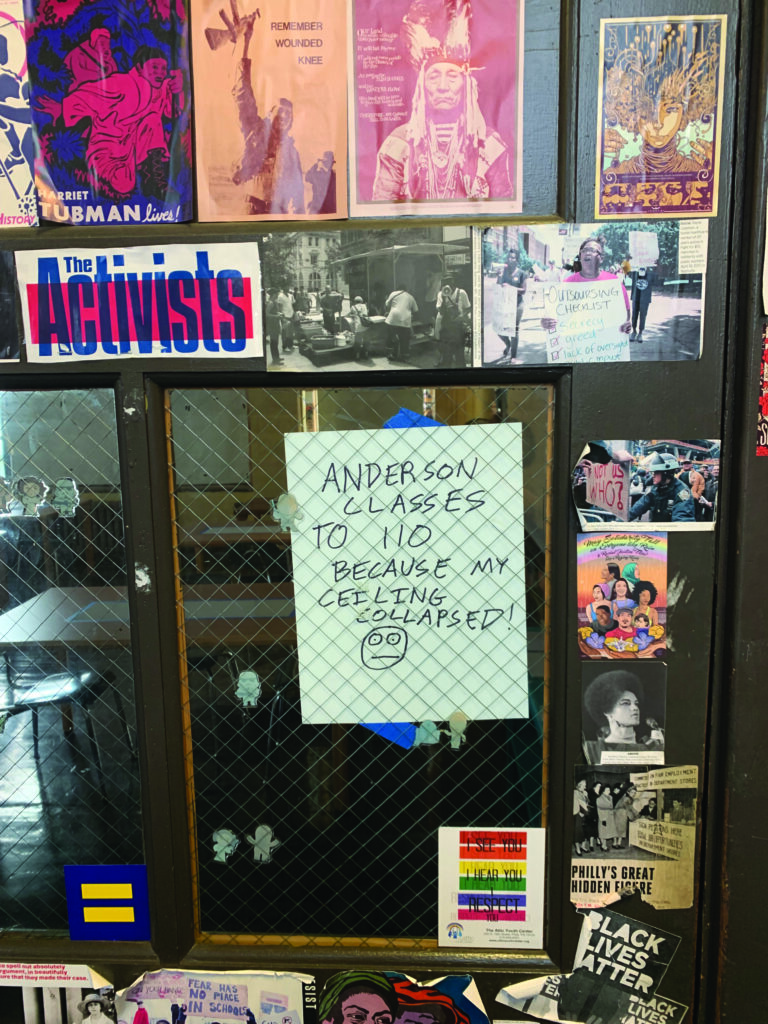

The next week I greeted the students waiting outside my classroom, unlocked my door, flicked on the lights, looked around the room, and immediately stopped the kids from entering. A roughly 3 foot by 5 foot oval-shaped area of the ceiling had collapsed and left debris all over the desks and floor. Big chunks of plaster and concrete had made dents in the hardwood floor. If we had been in that room the day before, students could have been seriously injured. There had been a leak in that ceiling all year and we’d been putting in the appropriate forms, but nothing had been done about it.

We relocated to the classroom next door that day. During my prep I sent an email with the photos to Kristen Graham, a journalist who covers the goings-on of Philly schools. She called and we spoke on the phone for nearly an hour. The next day the Philadelphia Inquirer published an article about building conditions across the district, which included the photos and story from our ceiling collapse. The day after the article was published, workers were in my classroom identifying the source of the leak and repairing the problem. I was teaching in the classroom next door when my students and I heard a loud smashing sound and then cursing from the workers through the collapsible wall. I ran over to make sure that everyone was OK. When I walked in, the workers were crowded around a massive concrete block about the size of a 4-year-old child, sitting in the middle of the floor underneath the collapsed part of the ceiling. Next to it was a piece of rusted rebar. The workers explained that one of them had been up on the ladder with a flashlight looking into the hole in the ceiling when suddenly that tiny bit of rebar became dislodged, and the concrete block tumbled down. If that block had hit someone on the head it would have killed them. The worker who’d been on the ladder was visibly shaken.

When I returned to class I kept wondering how it was that we had all become so desensitized to this kind of treatment. I asked, “Why do we keep walking into buildings every day that we can see are crumbling around us?”

“That’s just the way it is here, Anderson,” said one.

“Because what are we supposed to do about it? Just be mad about it all the time? I don’t want to be upset all the time,” added another.

“Well, that’s doing the same thing as the district accepting the debt and then accepting to pay it back. They could just stop paying. We could just stop coming,” another student suggested.

I went home feeling sad and angry. I realized that I had become desensitized. I had joked about how bad the conditions are to my friends, when there isn’t anything funny about it. I thought, “Well, at least no one got killed . . . at least now it’s finally getting fixed properly . . . at least this building is better than some of the others . . . at least we don’t have active asbestos in our classroom.”

To get by and feel happy and safe, I’d adjusted to the violence of working in a grossly underfunded school district. Like my student said, “I don’t want to be upset all the time.”

We need to find a way to transform that hurt into action. Teaching about district debt builds student capacity to fight back. If students are at school district headquarters demanding operational libraries and a reasonable student-to-counselor ratio, and the authorities claim that there is no money in the budget, it’s important for kids to be armed with the fact that 10 percent of the annual budget goes directly to debt repayment.

This year’s February court ruling that Pennsylvania school funding is unconstitutional proves that the continued organizing and pressure of educators, parents, and kids works. Next year I want to teach about their organizing tactics and successes too.

One last thing: It can feel daunting to try to teach about school funding and district debt. I am proud of myself for trying anyway, even if I felt shaky on the details. The idea that I need to be an expert in everything before I can teach it to anyone else is a hierarchical and toxic way of thinking. I will be courageous in sharing that this topic is new to me and explain that we are learning this together. This is humanizing, helps me feel less afraid to teach the issue, and builds camaraderie and solidarity as we step forward together toward a future we deserve. l

Resources

My District Debt Lesson: This is one of the versions of the lesson and activity I used to teach the debt impact on school districts. bit.ly/3NnoQso

Choose Your Own Debt Adventure Game: This is the role-playing choice game I created using Prezi. As of now, the Babette storyline and the school district storylines are up and running. bit.ly/3N2DSnC

Pennsylvania School Funding Lesson Plans: These are some amazing lesson plans put together by Mike Faccinetto, Holly Meade, Jess Keys, Tom Quinn, and Laura Boyce. They have designed lessons spanning grades 3–12. bit.ly/3oSAxy5