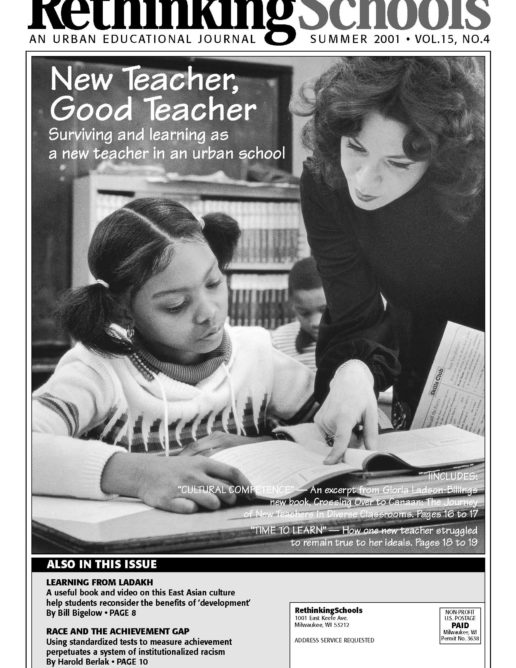

Teaching and Cultural Competence

What does it take to be a successful teacher in a diverse classroom?

In her new book, Crossing Over to Canaan: The Journey of New Teachers in Diverse Classrooms, Gloria Ladson-Billings details a program known as Teach for Diversity. This 15-month elementary certification program with master’s degree is specifically designed to prepare teachers to work in diverse learning environments.

The program started after Ladson-Billings and her colleagues in the Department of Curriculum and Instruction at the University of Wisconsin-Madison discussed their concerns that the department was not preparing teachers who could demonstrate a clear understanding and commitment to principles of human diversity, equity, social justice, and the intellectual lives of teachers.

Ladson-Billings writes that her work with the Teach for Diversity program was “informed by my previous research with successful teachers of African-American students. This work helped me develop a theoretical notion of culturally relevant pedagogy that is based on three propositions: academic achievement, cultural competence, and sociopolitical consciousness.” The excerpt below outlines some of the challenges facing the teaching profession and explains the concept of cultural competence.

— Rethinking Schools

I began teaching early adolescent students in a K-8 school in South Philadelphia in the late 1960s. Although I was a native Philadelphian, this part of the city was new to me. When I arrived about a month after the school year began, my classes were in chaos. The students were left to a series of substitute teachers and seemingly decided that school had not officially begun because their “real” teacher had not shown up. This disorganization was not surprising to me. I had no fond hopes that the students would be awaiting my arrival — attentive and prepared to move on in social studies and English. What was surprising was the “diversity” I experienced in South Philadelphia.

To the casual observer, I was teaching predominantly white, working-class students, along with a number of African-American students who were bused from West Philadelphia. I thought that myself. But as the year progressed, I learned that I was teaching white ethnic students — Italian Americans, Irish Americans, Jewish Americans, Polish Americans — of varied religious persuasions — as well as African-American students. I also learned that these differences mattered in specific ways, and any success I was to have in the school would be tied to my ability to develop a deeper understanding of the groups to which the children felt an affiliation.

THE TEACHER SHORTAGE

One of the current concerns plaguing the nation’s schools is how to find teachers who are capable of teaching successfully in diverse classrooms. Although teacher education programs throughout the nation purport to offer preparation for meeting the needs of racially, ethnically, culturally, and linguistically diverse students, scholars have documented the fact that these efforts are uneven and unproved.

Several factors interfere with the ability of teacher education programs to prepare teachers for diverse classroom settings. One factor that is rarely discussed in the literature is that most of the teacher education faculty are white. As I said earlier, there are approximately 35,000 faculty in the United States; 88 percent of the full-time education faculty are white; 81 percent are between the ages of 45 and 60 (or older). These numbers alone do not prove anything about the ability of the teacher education faculty. However, they may cause us to wonder about the incentive of teacher education programs to ensure that all of its graduates are prepared to teach all students.

One of my former graduate students decided to pursue a teaching credential after completing his master’s degree. He chose a credentialing program close to his home, which was in one of the nation’s most diverse sites. A month after he began his program, I received a letter from him:

The experience of my former student may not represent all teacher education programs, but one cannot but marvel at the irony of such a program in the midst of a community that comprises students of many racial, ethnic, cultural, and language groups. How is it that teacher education programs can be surrounded by diversity and continue to be oblivious to it?

WHAT DIVERSITY MEANS TODAY

The diversity that today’s new teachers face is qualitatively different from what I faced as a new teacher in the late 1960s. My students were clearly differentiated by their ethnic, cultural, religious, and racial differences during a time when such differences seemed more consequential; today, notions of diversity are broader and more complex. Not only are students likely to be multiracial or multiethnic, but they are also likely to be diverse along linguistic, religious, ability, and economic lines that matter in today’s schools.

The “success” of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement helped to create an African-American middle class with experiences and backgrounds different from their brothers and sisters who remained in the old neighborhoods. Indeed, changes in the economy and political climate created an African-American underclass that is less trusting of schools and education. Urban centers began to serve growing numbers of immigrant students from Mexico, Central America, and Southeast Asia. The working-class, ethnic neighborhoods of the 1960s knew nothing of the scourge of drugs like crack cocaine or diseases like AIDS. The industrial economy of the 1960s meant that there was plenty of work for people with high school diplomas and even less education. Homelessness was a condition left to indigent men who struggled with drugs and alcohol, not to families with school children.

In addition to the problems the students experience in their personal lives away from school, the schools create a whole new set of problems for children they deem different. As schools become more wedded to psychological models, students are recruited into new categories of pathology. Students who do not conform to particular behavioral expectations may be labeled “disabled” in some way, that is, suffering from attention deficit disorder, emotional disability, or cognitive disabilities. Students do in fact confront real mental and emotional problems, but we need to consider the way students’ racial, ethnic, cultural, linguistic, and socioeconomic characteristics are deployed to make their assignments to these disability categories more likely.

WHAT TEACHING WELL MEANS TODAY

Who are the teachers capable of transcending the labels and categories to support excellence among all students? Martin Haberman calls them star teachers; I call them dreamkeepers. But in both my work and that of Haberman, we have identified experienced teachers who knew how to teach well in challenging circumstances. Teaching well, in this instance, means making sure that students achieve, develop a positive sense of themselves, and develop a commitment to larger social and community concerns.

Such teachers are inspiring and admirable, but their ranks are decreasing with each passing school year. The question facing most urban school districts is how to ensure a faculty of effective teachers when there is high teacher turnover and relative inexperience.

One issue is that new teachers are the more vulnerable professionals in schools; they need to be nurtured and supported in the profession. They expect — and should receive — well-planned and implemented professional development that helps them learn about their work as they make those first, tentative steps in the profession.

Knowing that new teachers need support and providing such support are two very different things. In an attempt to make a more seamless transition between preservice and inservice, my colleagues and I developed a program for college graduates who have expressed a desire to teach school in communities serving diverse racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic populations. We called the program Teach for Diversity or TFD.

THE IMPORTANCE OF CULTURE

The average white teacher has no idea what it feels like to be a numerical or political minority in the classroom. The persuasiveness of whiteness makes the experience of most teachers the accepted norm. White teachers don’t understand what it is to “be ashy” or to be willing to fail a physical education class because of what swimming will do to your hair. Most white teachers have never heard of the “Black National Anthem,” let alone know the words to the song. Most have never tasted sweet potato pie or watched the intricate process of hair braiding that many African-American girls (and increasingly boys) go through. And although African-American youth culture has become increasingly popular, and everyone can be heard saying, “You go, girl!” and belies she has the right to sing the blues, the amount of genuine contact these people have with African Americans and their culture is limited.

Similarly, the growing Latino population has forced a change in popular culture. Ricky Martin, Christina Aguilera, and Enrique Iglesias are enjoying huge popular success. But most white teachers cannot speak even rudimentary Spanish — enough even to signal an emergency or satisfy a basic need. More disturbing is the way Latinos are racialized into a unitary category. Few teachers (and prospective teachers) know the distinctive histories of Mexican Americans, Puerto Ricans, Cuban Americans, Salvadoreans, Guatemalans, Peruvians or the countless groups who originate in the Spanish-speaking Americas.

The indictment is not against the teachers. It is against the kind of education they receive. The prospective teachers with whom I have worked generally express a sincere desire to work with “all kinds of kids.” They tell me that they want to make sure that the white children they teach learn to be fair and to get along with people different from themselves. But where is the evidence that the prospective teachers can get along with people different from themselves? When asked, most of my students admit that they have never gone to a movie or shared a meal or visited the home of a peer who is racially or culturally different. Some, because of program requirements or their own faith commitments, have worked in a soup kitchen or shelter or in other “helping” roles with people different from themselves. But these brief forays into the lives of “others” often serve to cement the impression that others are always needy and disadvantaged.

“Helping the less fortunate” can become a lens through which teachers see their role. Gone is the need to really help students become educated enough to develop intellectual, political, cultural, and economic independence. Such an approach to teaching diverse groups of students renders their culture irrelevant. There is nothing there to be learned, let alone built upon and developed. Certainly, every group has some “worthies” like Martin Luther King, Jr. or César Chávez, but even these cultural heroes have become sanitized to meet normative standards. Students are encouraged to be like (Martin Luther King, Jr., César Chávez, Sojourner Truth, Dolores Huerta, and so on) because they were “good Americans.” Rarely are students invited to learn about the way such people stood up to America (not just to a “few bad people”) and demanded that the country live up to its own democratic rhetoric.

Culture is a complex concept, and few teachers have an opportunity to learn about it. Most teacher education programs are founded on the social science discipline of psychology (and some sociology). Rarely do prospective teachers examine education through the discipline of anthropology. And although it is important for teachers to understand their students’ culture, the real benefit in understanding culture is to understand its impact on our own lives. Thus, the TFD program was interested in helping prospective teachers look at the way their cultural background influences and shapes the way they understand and act in the world.

NOTIONS OF WHITENESS

Helping students become culturally competent is not an easy task. First, it requires that teachers themselves be aware of their own culture and its role in their lives. Typically, white middle-class prospective teachers have little or no understanding of their own culture. Notions of whiteness are taken for granted. They rarely are interrogated. But being white is not merely about biology. It is about choosing a system of privilege and power. The white ethnic students in my first teaching job called themselves Italian or Irish or Polish. Their working-class backgrounds made it difficult, if not impossible, for them to identify with whiteness. In our current society, people with ethnic and cultural identities often find themselves choosing whiteness over those identities. Such a choice comes at a cost.

I gave a lecture at a local community college when a young man approached me at the end of the question-and-answer period and said, “You said a lot about Native American history and African-American history and Asian-American history, but what about white history — what about my history?”

I followed up with a question that seemed to startle the young man “Are you white?” I asked. “Or do you have an ethnic or cultural heritage other than white?” He responded by saying, “I’m Irish.” I then began to tell him about some of the aspects of Irish history — how the Irish were the first group the British exploited for slave labor in the Americas. I told him about the intricate clan structure the Irish had developed that allowed them to hold land in common and prevent exploitation. The young man knew nothing of this. I was not surprised. I suggested that he did not know his history because, somewhere along the line, his family may have chosen whiteness over all else. And when one chooses whiteness as a primary identity, one’s ethnic and cultural history disappears. All he has left to signal his existence is something about a potato famine and St. Patrick’s Day.

It would be simplistic and wrong to suggest that cultural and ethnic identities are fixed and discrete. Few Americans have a pure heritage or identity. But the customs and traditions we observe, the people with whom we associate, and the ideas we cultivate all shape our identities; in a society that places such priority on racial identity, we are naive if we attempt to ignore race. Indeed, ignoring race may prove to be a dangerous decision for some.

Teachers who are prepared to help students become culturally competent are themselves culturally competent. They do not spend their time trying to be hip and cool and “down” with their students. They know enough about students’ cultural and individual life circumstances to be able to communicate well with them. They understand the need to study the students because they believe there is something there worth learning. They know that students who have the academic and cultural wherewithal to succeed in school without losing their identities are better prepared to be of service to others; in a democracy, this commitment to the public good is paramount.

The above is condensed from Crossing Over to Canaan (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2001). This material is used by permission of Jossey-Bass, a subsidiary of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.