Support That Can’t Support

My induction program experience

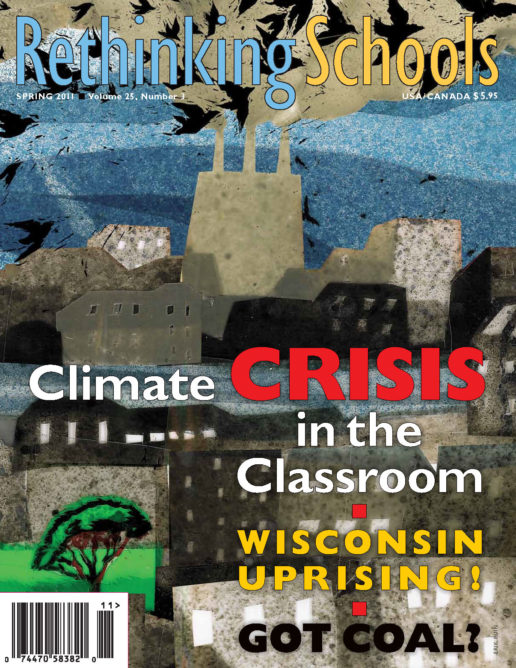

Illustrator: Diana Craft

It is a cloudy Wednesday afternoon in January, and I am at a critical juncture in my teaching. As a first-year teacher, trying to hold on to my passion and initiative, my developing professional compass is spinning.

Our weekly staff meeting is coming to an end. My 4th-grade cohort—all teachers on temporary assignment—stays seated at our table to finish a discussion with the principal. The day before, our principal met with us during lunch to ask if we would pilot a reading “regroup” project. Our assignment is to look at each student’s level for a specific reading standard and create homogeneous skill groups across the whole grade level. To accommodate teaching these new groups into our schedule, we need to find time for an additional 30 minutes of instruction in our already test-driven academic day. Our principal is very clear that this reading time comes in addition to the guided reading groups we already facilitate in our classrooms.

As my principal approaches the three of us, the inevitable result of the conversation is already sitting in the bottom of my stomach. Due to top-down pressure to improve test scores, the students in our school are increasingly looked at as data, not multidimensional human beings. If it is not tested, it is usually not taught. The untested subjects (social studies, science, art, music, PE) always get the short end of the stick.

Today is no exception. Our principal proposes we use our social studies and science time for the extra reading block, arguing that our most struggling readers can’t read the information from these two subjects’ textbooks. Even though I expected this, it is no easier to hear. The argument makes no sense. Questions fill my mind and disgust grabs my chest. Isn’t there a different way we could build reading skills without eliminating subjects that engage students and evoke critical thinking?

On that Wednesday, I desperately need to discuss the events of the day with an experienced teacher. In fact, I am part of an induction program, BTSA (Beginning Teacher Support and Assessment)—a California state program that is meant to offer support to new teachers as they exit the credential program and begin a job in a district. But I wonder what type of support my induction program will offer. Will the induction program foster my passion, initiative, and growth as a reflective professional educator? Or will the induction program be one more agent to promote the present testing agenda?

Induction Programs in Theory

More than 80 percent of new teachers across the United States participate in some kind of induction program. At least 30 states have a required mentoring program, and the idea of having structured induction programs for new teachers is only becoming more popular. The degree of structure within the programs varies. Some are highly structured, whereas others are merely a loose partnership between a mentor teacher and a beginning teacher (Russell).

Structuring an induction program for optimal support is critical. However, of equal (if not more) importance is looking at the pedagogical practices and theories illuminated within the induction programs. In my experience, our well-intentioned teacher-to-teacher induction program favors data analysis for testing progress, rather than the development of well-rounded professional educators.

BTSA is the pathway for beginning teachers to change a preliminary credential (issued as a result of successfully completing a credential program) into a clear (permanent) credential. The two-year BTSA program utilizes the FACT system (Formative Assessment for California Teachers). This system requires monthly meetings and the completion of four modules each year. New teachers identify, within their classroom teaching, their areas of strength and areas in which they require improvement. Through the four modules, the induction teachers focus on their weaker areas in the hopes of making progress. The modules focus on different skills and standards for the teaching profession.

An important component of BTSA is pairing each new teacher with a support provider. This guiding teacher is supposed to observe the induction teacher in the classroom periodically, offering assistance and advice. Unfortunately, my BTSA support provider is an assistant principal at a different school. I know better than to ask her questions that challenge the administration or the program itself, given the vulnerability of not only my job but also the jobs of my partner teachers. Ironically, having this mentor makes me feel more isolated than ever.

A flier for the BTSA induction program states the overarching purpose: “The goal of BTSA Induction is to support participating teachers in the process of being a reflective practitioner.” This sounds positive and powerful. In today’s education system, we need teachers who are well versed in reflection, who challenge themselves to reconsider their pedagogical practices to the benefit of their students’ learning.

However, at least in my district, in the implementation of the induction program, the focus on reflection and professional learning can get tangled up with the strings attached to high-stakes testing. As a result, the same one-dimensional educational ideas are being passed on to a district’s beginning teachers, focusing solely within the narrow confines of the testing agenda and leaving them no time to reflect on the multiple aspects of teaching. My experience with the focus module of the induction program—the inquiry project—reveals this disheartening reality.

The Limited Inquiry Project

At the January BTSA meeting, shortly after we are assigned the regroup project, we inductees are introduced to Module C, our third BTSA module of the year, which is an inquiry project. I listen as a program director begins to explain the project: “A teacher inquiry, or teacher research, is when teachers explore their teaching. You examine a specific area of your teaching by asking a question and then planning specific teaching practices to examine the question, gaining further insight into the area you wanted to explore,” she states.

This reminds me of my credential program. We discussed and participated in teacher inquiry. I am actually a bit excited to embark on an inquiry now that I have a classroom of my own. My mind wanders through the many questions I have had this year about the diverse needs of my energetic class of 33. I wonder how I can motivate Shane to be a positive, collaborative team member instead of mumbling negative comments about every assignment and every student. I wonder how I can get Jackson to believe in himself, in spite of his low self-esteem and anger at having both his parents in jail. I wonder how I can get some of my students who come into class with an attitude of white superiority—having grown up in a privileged, predominantly white neighborhood—to become interested in learning about the history of our state from the perspective of other cultures.

I catch my wandering mind just as the woman begins to talk specifically about the inquiry question itself. “You need to make the question specific. Remember, it needs to be based on a content standard. You want to see how many more students you can move to proficiency by the end of your inquiry.” I think I mishear her. I look up at the screen to see a projection of one of the module’s required pages. The page has four columns. The headings are far below basic, below basic, basic, and proficient/advanced. “This is where you record your data after the pretest.” She flips to an identical page with a different title. “And this is where you record the data after your summative assessment. You can see how well you did, how much the students learned.” I am stunned. What about all of the questions I have that don’t fit the narrow limits of this inquiry? I don’t know whether to laugh or cry at my naïveté about the purpose of this inquiry.

The regroup my principal requested we implement fits the requirements of the inquiry perfectly; it is based on an academic content standard, and it is focused on moving more students to proficiency. It has become clear that we don’t, in reality, have a choice about our inquiry.

It is painful plowing through the tremendous amount of work necessary to complete the module when I do not believe in my project. By the time I finish my inquiry project I have produced a 45-page document and a trifold presentation board. In fact, what I learn from my project is that if I add even more reading time to a child’s day, focus that reading on a specific standard, and use sentence stems from the test to teach the kids, then students will probably get one or two more questions correct. Is this the kind of reflection my induction program is hoping for?

Although the induction program speaks about promoting reflection, this “reflection” is totally linked to the analysis of data from standards-based assessments. Analysis of data does not help me to reflect on the classroom practices I genuinely want to explore.

Looking to the Future

Today I write as a recent graduate of the BTSA induction program. I am happy to say that I have jumped through all of the hoops and run the obstacle course. What am I left with? A 4-inch-thick binder, filled with pages of work. And a clear credential.

Although accomplishing the latter is an important step for me, I lost critical time and energy in navigating the roads that led to my piece of paper, my credential.

Did I grow as a reflective educator as a result of the induction program? No. I have developed a perspective as an educator due to my own efforts to hold on to my passion and initiative, despite the induction program. I have sought out teachers who offer the perspective I need to hear in conversation and to see in action within the four walls of a classroom.

I have a lot of respect for the directors and support providers, all of whom invest much time and energy into the induction program, but I think the implementation of the induction program’s goal needs to be altered.

The beginning teachers with whom I have traveled on this road are in the formative years of their careers, just as their students are in the formative years of their lives. A child only gets one chance at each grade. A score on a test lacks importance when compared with the path a student will walk for a lifetime. The same holds true for beginning teachers. We only get one chance at our first two years of teaching. The induction program ought to alleviate some of the pressure and offer opportunities for new teachers to reflect beyond data-driven instructional strategies. As new teachers, we need support with developing the other essential aspects of teaching, such as creating a positive classroom community, developing a perspective as a professional educator, and maintaining motivation within the classroom (for the students and teacher alike). As beginning teachers, we will one day be the foundation of our education system, teaching the children who will become the future of our nation.

Note

Russell, Alene. “Teacher Induction Programs: Trends and Opportunities.” Washington, D.C.: American Association of State Colleges and Universities, 2006. http://www.aascu.org/policy_matters/pdf/v3n10.pdf.