“Superachievers” vs. “Super Predators”: How the Racist Love of the Model Minority Is Weaponized Against Black and Asian American Students

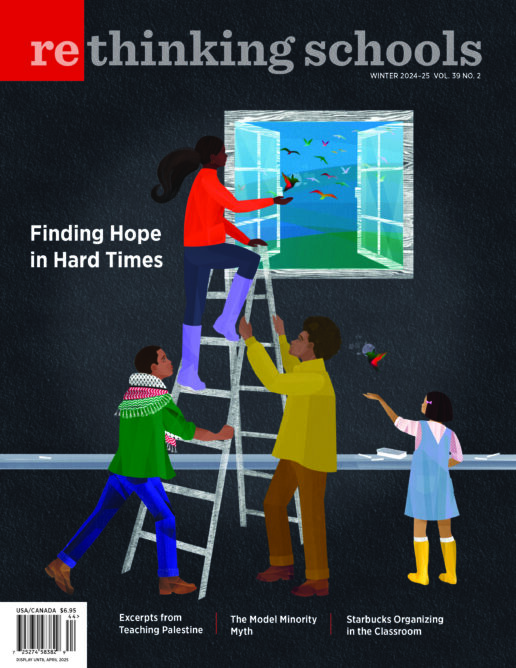

Illustrator: Howard Barry

In 1987, Time magazine published an article titled “The New Whiz Kids,” which labeled Asian American students as “superachievers.”

In 1996, then-First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton infamously referred to Black teenagers as “super predators” who lacked empathy and conscience.

Made nearly a decade apart, these two statements highlight how the racialization of Black and Asian American students have been tightly linked historically through the Model Minority stereotype — a stereotype rooted in white supremacy and anti-Blackness that has hurt both Black and Asian American students.

There was nothing new about Time’s article: It was merely a recycling of the well-worn stereotype of the Asian American Model Minority, which originated in January of 1966, when the New York Times published “Success Story, Japanese-American Style,” by William Petersen.

Centering around the idea that Japanese Americans have overcome racism better than other groups, Petersen crowed, “By any criterion of good citizenship that we choose, the Japanese Americans are better than any other group in our society, including native-born whites.” He went on to claim that, like European immigrants, Japanese Americans have also taken “advantage of the public schools, the free labor market, and America’s political democracy” and “climbed out of the slums, took better-paying occupations, and acquired social respect and dignity.” By comparison, Petersen contended, this has not been true for groups he labeled as “problem minorities,” specifically “negroes, Indians, and Mexicans.”

According to Petersen, education was “key” to Japanese American success. After interviewing Japanese American college students at UC Berkeley, he found them to be clean, neat, studious, and, importantly, law-abiding and respectful — unlike the “bohemian slob” students he saw protesting on campus at the time. Petersen also argued that Japanese culture pushes Japanese Americans to work hard and have an “achievement orientation,” something that he asserted is lacking in “lower-class Americans, whether negro or white.”

In December of that same year, U.S. News & World Report published its own Model Minority article titled “Success Story of One Minority Group in U.S.” This piece focused on Chinese Americans, calling them “a model of self-respect and achievement in today’s America.”

The article repeatedly asserted that Chinese Americans are self-sufficient and used this to continually assert the racist idea that Black people were too dependent on state support and were draining resources. At one point the article fallaciously argues that “At a time it is being proposed that hundreds of billions be spent to uplift Negroes and other minorities, the nation’s 300,000 Chinese Americans are moving ahead on their own — with no help from anyone else.” The article then went on to say that Chinese Americans have been successful because they are willing to work at any job, “don’t sit around moaning” about their situation, are good citizens with strong families, and are obedient and hardworking in their jobs and at school — all the while implicitly suggesting Black people were the opposite.

The article ends by quoting a social worker who asserts that “it must be recognized that the Chinese and other Orientals in California were faced with even more prejudice than faces the Negro today. . . . The Orientals came back, and today they have established themselves as strong contributors to the health of the whole community.”

These articles established the architecture of the Model Minority stereotype: Despite having experienced significant racism historically, due to hard work, cultural values, obedience, respecting authority, family structure, achievement orientation, valuing education, and self-reliance, Asian Americans have still been successful.

Further, by both tacit and explicit implication, so-called “problem minorities” — especially Black Americans — just need to stop complaining, take note of Asian American success, and simply realize that racism is not really a problem. Thus, the Model Minority stereotype was born in 1966 of racism, white supremacy, and anti-Blackness.

Of course, the appearance of the Model Minority stereotype at this time was not coincidental. The Watts Rebellion had occurred in 1965, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 had passed as well. The Moynihan Report — which advanced racist arguments that Black families were weak and that a culture of poverty was the reason for their social and economic status — was published in the same year.

In this context, the stereotype of the respectful, clean, and non-rebellious Asian American Model Minority also served as a racial counterpoint to the increasingly organized and militant Black and Brown Liberation movements of the time. Consequently, the Model Minority stereotype also serves as an argument about respectability politics and the “right” way to achieve racial justice through quiet hard work, rather than loud, disruptive, or “scary” protests.

From Fortune magazine declaring Asian Americans to be “America’s Super Minority” in the 1980s, to the racist, eugenicist Bell Curve arguing that Asians had the highest IQs of all races in the 1990s, to the Wall Street Journal, the New York Times, Bloomberg, the Economist, and CNBC all publishing articles promoting the Asian American Model Minority in 2015, media, politicians, and pundits have ensured the stereotype’s durability for nearly 60 years.

Educational achievement has also been central to the Model Minority narrative, where across the decades Asian American students have been called “academic marvels” by U.S. News and World Report, the “reigning academic stars of academia” with “dazzling academic success,” and “stellar” by the New York Times. As author Stacey J. Lee notes in her book Unraveling the “Model Minority” Stereotype, these portrayals of Asian American student success are consistently attributed to high expectations of parents, two-parent homes, Confucian values, being studious, being quiet, being obedient, working hard, and valuing education.

Like the more general stereotype, the Asian American Model Minority student also gets used against Black students. Rather than looking at racism and economic stratification as sources of educational disparities, the stereotype instead reinforces racist tropes of Black students being unintelligent, lazy, “bad,” and uncaring educational failures who lack discipline and drive, and who have low educational expectations compared to their Model Minority peers.

The Model Minority is based on a racist love — a kind of love that both upholds Asian Americans to be used against other racial groups while also subjecting them to ongoing anti-Asian hatred.

The Racist Love of the Model Minority

Ultimately, despite its portrayal as a “positive” stereotype, the Model Minority is based on a racist, white supremacist love — a kind of love that both upholds Asian Americans to be used against other racial groups while also subjecting them to ongoing anti-Asian hatred and violence. Reflecting on the rise in attacks on Asian Americans in the early 2020s, in her book Racist Love, Leslie Bow discusses how this love

transforms into racist hate with dizzying speed. . . . [R]acial feeling easily flip-flops its mode of existence. . . . For Asian Americans, hard-won taboos against hate speech evaporated overnight. . . . The contemporary moment of undisguised anti-Asian bias pulls me full circle: from philic to phobic, from compliment to slur. . . . [I]n the shift to racial hatred, what remains operative is racial feeling on a continuum, adoration and animosity as flip sides of the same coin.

To Bow’s point, over the last six decades, the “positivity” of Model Minority stereotype has never protected Asian Americans from the violence of white supremacy. From the early 1980s murder of Vincent Chin in Detroit by two recently laid off white male auto workers, to a white gunman killing five and wounding 32 Asian American schoolchildren in the late 1980s, to the white supremacist “dot busters” in New Jersey who violently targeted South Asian Americans in the 1990s, to the 2012 killing of six South Asian Americans at a Sikh temple in Wisconsin, to the thousands of reported incidents of anti-Asian hate that took place from March 2020 to March 2021 amidst the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, to the 2021 shooting of six Asian American women by a white male gunman in Georgia — the stereotype of the good, hardworking, and law-abiding Model Minority has never stopped Asian Americans from being seen as a threat to American whiteness. Indeed, one could easily argue that the racial exceptionalism underlying the stereotype of Model Minority success has likely only increased anti-Asian violence.

The Asian American Model Minority student has similarly been viewed as a threat to the education of white students. During the 1980s, newspaper articles regularly described Asian American students as “surging” like a “tidal wave” into elite universities, and graffiti saying “Stop the Asian Hordes” appeared at UC Berkeley. White university students also joked that UCLA (the University of California Los Angeles) stood for “University of Caucasians Living Among Asians,” that MIT (the Massachusetts Institute of Technology) was really an acronym for “Made in Taiwan,” and that UCI (the University of California Irvine) really meant “University of Chinese Immigrants.”

In March of 2011 a white UCLA student went viral on social media after posting a video titled “Asians in the Library,” where she complained about “hordes of Asian people” and racistly mimicked Asian languages. All of which supports Nolan Cabrera’s 2014 research, which found that even though Asian Americans are the only racial group in the United States to attend universities proportionate to the overall population, white college students still view Asian American students with resentment and feel they are over-represented in higher education. What some might find surprising is that, because of the stereotype, many Asian Americans have also come to resent themselves.

Internalizing Racist Love

The reality is that many Asian Americans have internalized the Model Minority stereotype as a kind of racial identity. As Erin Ninh, author of Passing for Perfect, explains:

. . . [T]he model minority is coded into one’s programming — racialization becoming feeling and belief — its litmus test is whether an Asian American feels pride or shame by those standards. If you have enjoyed what Tiger parenting memes say about you (laughed ruefully, maybe, but knowingly): Congratulations, you have tested positive. With your click, like, and share, you affirm an identity set apart from other racial groups: a feeling that our bar is higher.

The internalization of the Model Minority stereotype means that if we are not successful, society does not see us as “real” Asian Americans, nor do we see ourselves as “real” either. This reality moves Ninh to ask a particularly painful question: “ [I]f Asian Americans are recognized as persons by their communities and their country only by the success frame, then whose public identity is a failure allowed to use? Whose racial reputation and likeness if not their own?”

Consequently, there is a lot of evidence that the Model Minority stereotype contributes to the poor mental health of Asian Americans, especially students. For instance, one study of Asian Americans aged 18–30 found that pressures associated with the Model Minority and racial discrimination in school resulted in increased stress, what some have specifically referred to as “model minority stress.”

In addition, the Model Minority stereotype is predicated on a kind of Asian American, able-bodied perfection, such that we do not risk asking for help — since needing help means we are imperfect and potentially misaligned with social, community, and even our own expectations of ourselves as Asian Americans. As such, research also finds Asian Americans resist reporting bullying and harassment and are also unlikely to seek mental health supports and that many doctors incorrectly presume that Asian Americans face fewer mental health issues than other racial groups. Many Asian Americans have their psychological conditions underdiagnosed and misdiagnosed because of this.

Hence, as one Asian American psychologist explains in an article for Axios, “We self-harm. We quietly continue to do our homework, even though we’re super depressed or anxious. We act out inside the house, but it never shows outside the house. . . . So this system of schools has . . . always been like, ‘Oh, you’re good, you’re fine.’”

These issues all contribute to the fact that suicide is the second leading cause of death for Asian Americans ages 15–34, with the highest concentration between ages 20–24. For Asian Americans, the Model Minority stereotype is literally killing us.

Clearly, the Asian American Model Minority stereotype comes at a cost: It supports anti-Black racism and deficit views of Black people, subjects Asian Americans to white supremacist fears and violence, and it damages the Asian American psyche. But what if all that stereotypic Asian American achievement — that magical sauce for Model Minority success — is not magical at all, but instead simply confirms what we already know about income and education disparities in the United States?

But what if that magical sauce for Model Minority success is not magical at all, but simply confirms what we already know about income and education disparities?

Confirming the Obvious

If you took most educational data on face value, you might conclude that Asian Americans really are a Model Minority. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, in 2022 Asian American students were tops among all racial groups in total NAEP and SAT scores, and data from 2021 shows a four-year college enrollment rate for Asian Americans of nearly 76 percent, compared to a rate between 40 and 43 percent for Black and Latine students. In addition, census data from 2022 shows that 61 percent of Asian Americans have college degrees, a rate that significantly outpaces Latine peoples (20.8 percent), Black Americans (28.1 percent), and whites (41.9 percent).

However, what is lost in this data is that Asian American achievement simply proves what has been obvious across decades of educational research: Parental education and economic class have almost an ironclad correlation with academic achievement.

After decades of Asian immigration to the United States being illegal, the federal government passed the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, giving preference to Asian immigrants who already held higher education degrees and who had professional skills. These had a profound effect on the educational outcomes of Asian Americans. For instance, between 1966 and 1977, more than 80 percent of the immigrants from India were professional and technical workers, including 40,000 engineers, 25,000 doctors, and 20,000 scientists with PhDs. As another example, between 1966 and 1985, 25,000 well-educated nurses immigrated to the United States from the Philippines. Importantly, the Pew Research Center estimates that more than 98 percent of Asian Americans either immigrated after 1965 or are descendants of post-1965 immigrants.

Currently, U.S. immigration policy gives preference to immediate family of permanent U.S. residents and gives second preference to educated professionals. Wealthy immigrants can also gain entrance to the United States by investing in U.S. businesses in the amounts of either $900,000 or $1.8 million. Again, these rules influence the Asian American population. Data from 2017 to 2019 shows that more than 60 percent (more than 490,000) of the immigrants to the United States were from Asia, mostly on the H-1B visa used heavily by the technology, banking, and entertainment sectors.

There is also a selection process in many Asian home countries that limits who immigrates to the United States. As Prachi Gupta explains in They Called Us Exceptional, in India, “middle- and upper-class Indians from dominant castes typically access the best schools and jobs that feed into opportunities in America, which favor immigrants who bring specialized skills in tech and science.” The result is a highly selective Indian American community where 68 percent of Indian immigrants to the United States already have a college degree. This rate is 3.5 times that of the general U.S. population, and, more importantly, it is nine times that of the general population in India itself.

Research consistently shows that achievement markers like college attainment and SAT scores correlate very strongly with family income and education levels of parents. Given that so much of the Asian American population is sharply skewed toward a select group of immigrants, the majority of whom likely came to the United States with college degrees and professional jobs already in hand, it is no wonder large numbers of Asian American students are getting high test scores and attending college.

Southeast Asian Americans also confirm the tight relationship between levels of family income and education with academic achievement. Since 1975, refugees from Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam, including the Khmer and Hmong/Hmoob peoples, have been resettled in the United States after fleeing persecution due to U.S. imperialist military incursions in their home countries. While initial decades of resettlement resulted in more than 1.1 million refugees being relocated to the United States, more recent Southeast Asian immigrants have arrived through visas for family members or employment such that there are more than 2.5 million Southeast Asian Americans in the United States.

Contrary to the Asian American Model Minority stereotype, nearly 44 percent of Southeast Asian Americans are officially low-income, with 460,000 of those officially living in poverty. Notably, Hmong/Hmoob Americans experience a 58 percent low-income rate, with 26 percent officially living in poverty — rates nearly double that of white Americans and on par with Black Americans. College attainment rates for Southeast Asian Americans are also significantly lower than other Asian American groups: For Vietnamese Americans it is 29 percent, Burmese Americans 21 percent, Hmong and Laotian Americans 18 percent, and Cambodian Americans it is 16 percent. Data from California (where the highest concentrations of Southeast Asian Americans live) also indicates that almost 30 percent of Southeast Asian Americans there have not earned a high school diploma.

Whether at the top or the bottom of income and education levels in the country, Asian American academic achievement simply confirms the obvious fact that our system of education reproduces social and economic inequities that privilege families with higher levels of education and financial resources.

It is the mythology of Horatio Alger’s rags-to-riches, pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps American meritocracy, only this time in yellowface.

Model Minority Divestment

In 1903, in The Souls of Black Folk, W. E. B. Du Bois posed this question to African Americans: “How does it feel to be a problem?” Nearly 100 years later in The Karma of Brown Folk, Vijay Prashad suggests that the question for the Asian American Model Minority is instead “How does it feel to be a solution?”

And that is just it. Framed as a Model Minority, Asian Americans are presented as a solution to racism: Just keep your head down, work hard, stay quiet, be self-sufficient, respect authority. It is the mythology of Horatio Alger’s rags-to-riches, pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps American meritocracy, only this time in yellowface.

When it comes to the Asian American Model Minority stereotype, we are left with a choice: Maintain this investment in the Model Minority and, by extension, maintain the investment in white supremacy, racial capitalism, settler colonialism, and anti-Blackness that comes with it, or divest from the stereotype entirely — including ditching the internalized identity for Asian Americans themselves — because it does not serve anyone’s humanity.

Such divestment would require developing more critical understandings of Asian Americans by all racial groups, as well as developing critical, radical understandings of the deep connections between Asian Americans and non-Asian Americans — what Pulitzer Prize-winning author Viet Nguyen refers to as “expansive solidarity.”

Part of this process could include uncovering, radically reconstructing, and relearning Asian American histories that includes progressive, radical, and even revolutionary activism that operates in direct contradiction to the Model Minority stereotype. This could include learning about historical heroes like Yuri Kochiyama and Grace Lee Boggs, both of whom were radical Asian American activists who worked closely with Black community organizers on issues of justice and solidarity. More recent examples could include activists like Connie Wun, Tamara Nopper, and Dylan Rodriguez, all of whom have been making deep and serious connections between Asian American communities and the abolitionist movement. Similarly, groups like Tsuru for Solidarity, Red Canary Song, the Asian Prisoner Support Committee, AAPI Women Lead, and Butterfly have also been working on a wide range of abolitionist projects.

We should also be supporting K–12 Asian American Studies curriculum, especially by those doing it from a more liberated Ethnic Studies approach. For instance, we can see this work being brought to schools, communities, and teachers through Sohyun An and Noreen Naseem Rodriguez’s “Asian American Studies Curriculum Framework,” which asks students to critically consider “Imperialism, War, & Migration,” “Citizenship & Racialization,” “Resistance & Solidarity,” and “Reclamation & Joy.” An and Rodriguez have continued this work with their colleague Esther Kim through their excellent book Teaching Asian America in Elementary Classrooms, which provides a strong conceptual framing along with concrete examples for helping students develop critical consciousness surrounding Asian American histories and communities.

These examples demonstrate the potential of Asian American activists in concert with K–12 Asian American Studies to show how Asian Americans are deeply connected to all racial groups who have struggled against settler colonialism, anti-Black racism, and white supremacy. Indeed, recognizing these connections harkens back to the very origins of the racial category of “Asian American” itself, which largely grew out of the Black and Brown power movements of the late 1960s.

Ultimately, there is nothing positive about the Model Minority stereotype. The racist love of the Asian American student superachiever simply helps justify the white supremacist framing of Black youth as super predators. In the process it flattens the humanity of Asian Americans, disregards the material role that conditions of immigration play in educational achievement, causes mental trauma among Asian Americans, and gets used to argue that racism does not exist — all the while promoting white supremacist beliefs about Black and Brown peoples. The Model Minority needs to be abandoned as a racist stereotype and replaced with an identity that is anti-racist and based on expansive solidarity with other peoples.